| Trans | Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften | 0. Nr. | August 1997 |

|

| Goals of Culture and Art |

Kim H. Veltman (Maastricht) |

If our goal is truly a systematic access to culture in all its forms, we need a system that includes art in museums, texts in libraries and archives, performances in concert halls and theatres as well as other sources on the Internet. In spite of many important initiatives such as the Dublin Core, the Resource Description Format, the Interoperability Forum and many metadata initiatives we are not in a position to do this today. For the purposes of this paper three simple figures will suffice to make our initial point.

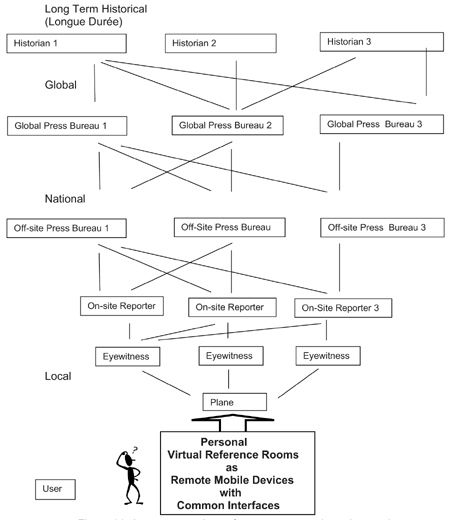

We shall begin with a relatively "simple" contemporary event, which could either be negative as in a plane crash or positive in the case of some triumphant parade or festival. At the local scene all the details of this event will be recorded. We will read in the local paper of who was killed, who their families were, how this has affected their

neighbours, their colleagues at work and so on. At the regional level the same event will be recorded as a plane crash and a smaller number of details concerning the most important crash victims will be provided (figure 13). At the national level, there will be a more matter of fact report of yet another plane crash. At the global level, the actual event is not likely to be described. Rather we shall probably witness a tiny fluctuation in the annual statistics of persons who have died. In historical terms, say the statistics concerning deaths in the course of a century (what the Annales School might call the longue durée), this fluctuation will become all but invisible.

This example points to a first fundamental problem concerning meta-data. Those working at the local, regional, national and historical levels typically have very different foci of attention, which are frequently reflected in quite different ways of dealing with, recording and storing their facts. The same event, which requires many pages at the local level, may merely be recorded as a numerical figure at the historical level. Unless there is a careful correlation among these different levels, it will not be possible to move seamlessly through these different information sources concerning the same event.

Implicit in the above is also an unexpected insight into a much debated phenomenon. Benjamin Barber, in his Jihad vs. McWorld,(190) has drawn attention to a seeming paradox that there is a trend towards globalizations with McDonalds (and Hiltons) everywhere and yet at the same time a reverse trend towards local and regional concerns as if this were somehow a lapse in an otherwise desireable progress. Looking at the above diagram (figure 13) it becomes clear why these opposing trends are not just a co-incidence. Clearly we need a global approach if we are to understand patterns in population, energy and the crucial ingredients whereby we understand enough of the big picture in order to render sustainable our all too fragile planet. But this level, however important, is also largely an abstraction. It reduces the complexity of the everyday into series of graphs and statistics which allow us to see patterns which would not otherwise be evident. Yet in that complexity, are all the facts, all the gory details which are crucial for the everyday person. Thus trends towards CNN are invariably counterbalanced by trends towards local television, local radio, community programmes, local chat groups on the Internet. This is not a lapse in progress. It is a necessary measure to ensure that the humane dimension of communication remains. In retrospect, Marshall McLuhan's characterisation of this trend as one towards a "global village" is much more accurate because it acknowledges the symbiotic co-existence rather than the dualistic opposition between the two trends.

To return to the problem of meta-data the problem becomes clearer if we pursue the hypothetical case of a plane crash from a slightly different point of view (figure 14). At the event there are usually eye-witnesses. For the sake of our illustration let us posit that there are three. There will also be on-site reporters who may not have been eye-witnesses. Again we shall posit three. They send their material back to (three) off-site press bureaus. These gather information and send them on to (three) global press bureaus. This means, that in our hypothetical example, the "event" has gone through some combination of 12 different sources (3 eyewitnesses, 3 on-site reporters, 3 off-site press bureaus and 3 global press bureaus, ignoring for the moment the fact that the latter institutions will typically entail a number of individuals). When we look at the six o-clock news on the evening of the event, however, we are usually presented with one series of images about the event.

It may in fact be the case that all twelve of the intermediaries have been very careful to record their intervention in the process: i.e. the meta-data will often be encoded in some way. What is important from our standpoint, however, is that we have no access to that level of the data. There is usually no way of knowing whether we are looking at eyewitness one as filtered through on-site reporter two etc. More importantly, even if we did know this, there would be no way of gaining access at will to the possibly conflicting report of eyewitness two, on-site reporter three and so on. There may be much rhetoric about personalisation of news, news on demand, and yet the reality is that we have no way of checking behind the scenes to get a better picture.

Some may object that such a level of detail is superfluous. Often this is true. If the event is as straightforward as a plane crash all that is crucial is a simple list of the facts. But the recent bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Kosovo offers a more complex case. We were given some facts: the embassy was bombed but not told how many person were killed. We were told that the Chinese objected as if they were being unreasonable and only many weeks later were we told that this had been a failed intervention of the CIA. Until we have useable meta-data which allows us to check references, to compare stories and arrive at a more balanced view, we are at the mercy of the persons or powers who are telling the story, often without even being very clear as to who is behind that power. Is that satellite news the personal opinion of the owner himself or might it represent the opinions and views of those in whose influence they dwell?

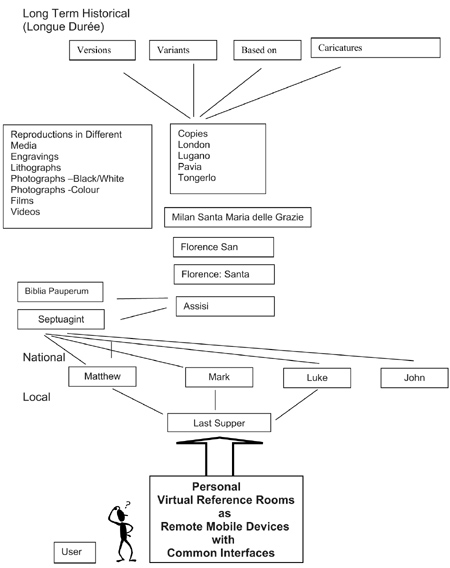

The problems concerned with these contemporary events fade in comparison with historical events, which are the main focus of our cultural quest. It is generally accepted that in the year 33 A.D. (give or take a year or two depending on chronology and calendar adjustments) there occurred an event, which might be described as the most famous dinner party ever: the Last Supper. From a contemporary standpoint there were twelve eyewitnesses (the Apostles) of whom four were also the equivalents of on-site reporters (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John). In today's terms, their reports were syndicated and are better remembered as part of a collection now known as the New Testament. That work went through various editions until it was revised as the Septuagint - a collation of all the reports of the time minus the meta-data tags. Popular versions with less texts and more pictures were also produced: expurgated equivalents of a Daily Mirror known as the Biblia pauperum.

The theme was then taken up by the Franciscans in their version of billboards -- without the advertising fees - known as fresco cycles. This idea developed in Assisi was marketed in their Florentine branch known as Santa Croce where the idea caught on and soon became the rage, so much so that the Dominicans soon used it in San Marco and elsewhere including the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie where Leonardo da Vinci gave a new twist to what had by now effectively become the company slogan. The idea soon became part of the Church's international marketing strategy. Copies appeared on walls as billboards, or rather, paintings in Pavia, Lugano, Tongerlo and eventually London. As part of the franchise strategy multi-media was used. So there were soon reproductions in the form of engravings, lithographs, photographs, three-D models, and eventually even films and videos. In the old tradition that imitation is best form of flattery, even the competition used the motif, culminating in a version where Marilyn Monroe herself and twelve of her Hollywood colleagues made out of the Last Supper a night on the town.

As a result of these activities in the course of nearly two millennia, there are literally tens of thousands of versions, copies and variants of the most famous dinner in history, which brings us back to the problems of meta-data. If I go to one of the standard search engines such as Yahoo or Altavista and type in Last Supper, I am given an indiscriminate number of the tens of thousands of images concerning the event, which happen to be on-line, or to speak technically, a subset of somewhere between 10 and 30% of that amount which have been successfully found by the leading search engines.

There is no way of limiting my search to the text versions of the original reporters, to large scale wall sized versions in the scale of Leonardo's version which was eight by four meters, let alone distinguish between Franciscan and Dominican versions, authentic copies as opposed to lampoons, caricatures and sacrilegious spoofs. To a great expert requiring a system to find such details might seem a little excessive because they might know most of these things at a glance. But what of the young teenager living in Hollywood who, as an atheist, has no religious background and sees the version with Marilyn Monroe for the first time? How are they to know that this a spoof rather than something downloaded from a fifties version of CNN online? A true search engine would help not only the young Hollywood teenager but also help every true searcher. Indeed it should provide truth even if the searcher is "false."

To achieve these will require more than quick fixes. Entailed is much more than scanning in all the evidence. It goes without saying that the system must reflect all the languages of the world, which is becoming possible through Unicode. We need the materials in some form equivalent to Standardized General Markup Language (SGML). As was noted earlier (figure 7), we need to be able to take a term or concept and contextualize it. We need to be able to go from any term to all the ways in which it appears in different classification systems and thesauri. We need to be able to trace how an individual author uses that term, to consult the given texts of the author in which that term occurs in all their versions and editions. Similarly we need access to the history of the corpus of texts by an author, with reference to the different ways they were received. (Just as there are fashions in clothes there are fashions in the way authors are appreciated. There were periods in the past few hundred years where even Leonardo da Vinci faded out of the public eye). Ultimately we also need access to information about the quality of the interpretations we are consulting. (Is the person who claims Leonardo was insignificant qua his contribution to science, someone who has actually read the texts?).

| Individuals and Concepts | |

| 1. | classification of term |

| 2. | single term of an individual |

| 3. | single text of an individual |

| 4. | corpus of an individual |

| 5. | quality of corpus |

| Objects/events | |

| 1. | resolutions and layers of image in one medium |

| 2. | copies, versions etc. of same image |

| 3. | relevant maps with boundaries adjusted over time |

| 4. | relevant calendars with instant conversion to equivalents |

| 5. | resolutions in detail from local to global |

| 6. | versions etc. of present event |

| 7. | versions etc. of past event. |

| Figure 16. New kinds of meta-data which are needed to achieve the vision of multimedia access to the world's cultural heritage. | |

With respect to objects we need a systematic correlation of all images concerning them, in all their resolutions, in all the layers of the object (through methods such as infrared reflectography), as well as all the copies and versions of those paintings or objects. We need not just contemporary maps to show us the locations of these objects but also historical maps which reflect the changing boundaries of countries over time. (As a result a query about Poland in the fourteenth century will search a different area of Europe than a query about Poland in the twentieth century). We need adjustable chronologies. And as noted in the diagrams above (figures 13-15) we need seamless movement among resolutions in detail from local to global; different versions, etc. of a present event and versions etc. of past event. To achieve this new form of meta-data a long-term project within the European Commission may be necessary.

In the early days of literacy in the West, a series of rules for the use of language evolved. This gradually led to the fields of grammar, (which dealt with the structure), dialectic, (which dealt with the logic) and rhetoric (which dealt with the effects of language). Together grammar, dialectic and rhetoric became the trivium, the humanities side of the seven liberal arts (which had its proto-scientific side in the quadrivium of mathematics, arithmetic, astronomy and music).

| Structure | Grammar | Inflexional forms | |

| Syntax | SGML, XML | ||

| Dialectic | Logic | Search for truth of statement | RDF |

| Semantic=Meaning=Semasiology | VHG | ||

| Rhetoric | Effect | Expression, Style | CSS/XSL |

| Figure. 17. Links between the ancient trivium and recent Internet developments | |||

When the Internet began in 1969 it was intended primarily to provide new ways for humans to communicate at a distance. In the past decades, have seen the emergence of a new challenge for the Internet: to provide new ways for machines to communicate with each other without the intervention of humans. This quest helps to explain why the theme of meta-data has become central to the world of computers. In the process it is instructive to note that groups such as the World Wide Web Consortium and the Internet Society are effectively engaged in re-formulating in electronic form, the rules of grammar, dialectic and rhetoric. The syntax aspects of grammar are covered by Standardized Graphical Markup Language (SGML) and eXtensible Markup Language (XML). Recent developments with respect to a Virtual Hyperglossary (VHG)(191) are addressing semantic elements of dialectic. Elements of expression and style relating to rhetoric are being covered by Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) and eXtensible Style Language (XSL, cf. figure 17). In other words, the Internet is not just about scanning in our cultural objects and other bits of content. It is also about finding electronic equivalents for all our rules and definitions of knowledge.(192) And ultimately it is changing our conceptions of knowledge itself. The challenge that faces us is to ensure that these transformations reflect all the diversity of our being rather than reducing us to the limitations of some algorithm. That is why the goals of culture and art are so essential for our future.

© Kim H. Veltman (Maastricht)

Anmerkungen:

(190) Benjamin Barber, Jihad vs. McWorld, New York: Times Books, 1995.

(191) Peter Murray Rust, Lesley West, "Terminology, Language, Knowledge on the Web: Some Advances Made by VHG," TKE '99. Terminology and Knowledge Engineering, Vienna: TermNet, 1999, pp. 618- 624.

(192)

This has recently been discussed in another context in the author's

opening keynote for the Terminology and Knowledge Engineering

(TKE '99) Conference: Webmeisterin: Angelika

Czipin

"Conceptual Navigation in Multimedia Knowledge Spaces,"

Innsbruck, 1999.

last change 30.1.2000