Innovations and Developments in Psychology and Education: Do Literacy Difficulties in Namibian Herero-English Bilingual School Children Occur in One or Both Languages?

Kazuvire R. H. Veii (Department of Psychology, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia)

[BIO]

ABSTRACT

This longitudinal study focused on Namibian bilingual school children’s possible evidence of literacy difficulties in two languages, namely, Herero, the children’s first language (L1) and English, their second language (L2), at Time 1 and Time 2 respectively. The aim of the study was three-fold: (1) to identify the cognitive and linguistic factors that may be related to literacy difficulties in this cohort of bilingual children, (2) to identify potential cases of "differential dyslexia" in this cohort, and (3) to assess the assumptions of the central processing hypothesis and the script dependent/orthographic depth hypothesis with regard to literacy development and difficulties. Five cases of children who presented with evidence of poor literacy skills were selected from a sample of Grade 3 children for whom data were available at Time 1 (Grade 3) and Time 2 (Grade 4) of testing. At Time 1 there were 40 children and at Time 2, 30. The children who constituted the five cases were available at both Times 1 and 2. The results pointed toward an association between cognitive/linguistic factors, on the one hand and, literacy difficulties in this cohort, on the other. Furthermore, the results also indicate that three out of the five cases of children selected presented with literacy difficulties in both languages, indicating that if literacy difficulties occurred in the one language, they were also likely to occur in the other. At the same time, the results also show that two of the five cases of children with literacy difficulties showed persistent literacy difficulties in L2 only at Time 2 after presenting with L1 and L2 literacy difficulties at Time 1. These findings seemed to be consistent with the views of the central processing hypothesis and the script-dependent hypothesis.

Introduction:

Two competing theoretical perspectives, namely, the script dependent hypothesis and the central processing hypothesis provide opposing accounts for the development of literacy and the nature of literacy difficulties in different languages. The script dependent hypothesis posits that reading development in different languages varies in accordance with the transparency or regularity of a particular orthography. Irregular (deep) orthographies use more complex relationships between letters and sounds. These differences in the letter-sound correspondence rules lead to variations in the prevalence and patterns of reading difficulties from one language to another, as well as to differences in the development of reading processes and skills between languages (Gholamain & Geva, 1999). The deeper the orthography, the more complicated the process of phonetic encoding, the slower the acquisition of literacy and, ultimately, the more prevalent and severe the reading problems. In contrast, consistent, transparent orthographies permit a simple, direct one-to-one correspondence between letters and sounds of words. As such, accurate word recognition skills are assumed to develop more slowly in less transparent languages than they do in more transparent orthographies (Gholamain & Geva, 1999; Geva & Siegel, 2000). Hence, the central processing hypothesis assumes a universal approach to literacy development, proposing that reading development is not contingent upon the type and the nature of the orthography. Rather, common underlying linguistic and cognitive processes (e.g., working memory, verbal ability, naming, and phonological skills) influence the development of reading across different languages. Therefore, children deficient in such processes are more at-risk for developing reading/literacy difficulties (Gholamain & Geva, 1999).

In a multilingual context, a child’s first language background is an important factor in developing literacy in an alternative language. It is equally important in informing the relevant educational authorities as to whether or not literacy difficulties occur in one or more of the languages in which a child is developing literacy skills. Different languages, depending on the depth and regularity of their orthographies, place a certain degree of cognitive and linguistic processing demands on the child. For example, transparent, regular, or shallow orthographies such as Herero, may place less demands on the cognitive and linguistic processing systems of a child in the process of developing literacy. In contrast, however, less transparent, deep, or irregular orthographies such as English may place much greater demands on a child’s cognitive and linguistic processing systems. A situation where a child is developing literacy in two or more languages differing in orthographic depth may result in an uneven development of literacy in each or one of the languages. A child inherently at risk for literacy difficulties developing literacy in an irregular orthography may be at an even much greater disadvantage and, may as a result, be delayed in developing appropriate literacy skills, perhaps more so in the less transparent orthography.

A situation where a child may fail to develop literacy in one language but not in another is known as "differential dyslexia" (Smythe & Everatt, 2002). This is all due to the fact that literacy difficulties are attributable to different underlying cognitive and linguistic causes and that cognitive and linguistic deficits that impact upon one language may not necessarily have the same effect in another language (Smythe, 2002). Thus, depending on the magnitude of the cognitive and linguistic demands of a language, a bilingual child is likely to present with symptoms of literacy difficulties in the language with more stringent cognitive and linguistic demands rather than in both languages.Findings from studies that investigated literacy difficulties in bilingual children (Ocampo, 2002); (Veii, 2003) and (Everatt, Smythe, Ocampo, & Veii, 2002) seem to point to the possibility that literacy difficulties may be language-specific.However, individuals presenting with differential literacy difficulties may be rare (Everatt, Smythe, Ocampo & Veii, 2002) and further studies are needed before conclusive evidence is found to confirm the existence, or the lack of, a differential diagnosis. Other studies examining differential dyslexia have provided some evidence for this phenomenon. For example,Leker & Brian (1999) described a patient who had an acquired reading difficulty in Hebrew but not in English. Wydel & Budderworth (1999) reported a single case of a child who showed evidence of dyslexia in English (L1) but not in Japanese (L2). Kline & Lee (1972) assessed children who were acquiring literacy in English and Chinese and found that the majority of the children had no problems with reading and writing in both languages, some had trouble with English but not with Chinese while others had trouble with Chinese and not with English. Finally, Miller-Guron & Lundberg (1997) have identified Swedish children who presented with dyslexia-like deficits in their L1 but presented no such deficits in English (L2).

This evidence may be consistent with the script dependent hypothesis (literacy difficulties will vary from one language to another given the differences in the orthographic depth of the languages). However, a different interpretation of these findings may be reflecting different manifestations of literacy difficulties (dyslexia) across different orthographies; that is, literacy difficulties can occur in different languages or in two languages at the same time as a result of the same deficient cognitive-linguistic processing skills that may occur in both languages. How these literacy difficulties manifest themselves, however, will be a function of the orthographic depth of a given language.

In the case of the cohort studied here, for example, literacy difficulties may exist in Herero, their L1, only but not in English, their L2, or only in English but not in Herero. On the other hand, it may also be possible that literacy difficulties may exist in both Herero and English and manifest themselves in different underlying cognitive and linguistic processing areas in both languages where "cross-contamination" may occur. For example, phonological deficits in Herero may be reflected in rapid naming deficits in English.

Literacy development in bilingual/multilingual children

The process of literacy development in bilingual children may have implications to the literacy difficulties they may encounter in the languages in which they are developing literacy. If, for example, cross-linguistic transfer of phonological processing skills can influence the development of biliteracy or multiliteracy, it may be plausible to argue that literacy difficulties that occur in one language may also occur in the other language, for if the prerequisite cognitive and linguistic processing skills can affect literacy development in the L1, then they could also have the same effect on L2 literacy development. Considering the fact that bilingual or multilingual children are exposed to two or more language systems at more or less the same time and, at an early age, it is possible that they develop sensitivity to the sounds of the two or more languages they are exposed to. This being the case, the knowledge of two or more sound systems should augment bilingual children’s literacy development in the L2 as well as in the L1 (Byalistok & Herman, 1999). The concurrent development of phonological processing skills in bilinguals’ languages may put them at an advantage when learning to read and write in these different languages because of the potential for cross-linguistic transfer of phonological awareness. For example, L1 phonological awareness facilitates L1 literacy development. At the same time, L1 phonological awareness may transfer to L2 literacy development while L2 phonological processing skills may also generalize to L1 literacy development. Finally, second language phonological awareness may facilitate the development of literacy in the second language. Thus, if L1 phonological awareness does indeed contribute to L2 literacy development, and L2 phonological awareness facilitates L1 literacy development, then cross-linguistic transfer of phonological awareness is indeed a reality (Comeau, Cormier, Grandmaison, & Lacroix, 1999). Furthermore, the prediction of L1 and L2 literacy development within and across languages may be an indication that similar cognitive processes possibly underlie literacy development in both L1 and L2. As such, individual differences in phonological processing skills can be an indication of smooth or problematic development of L2 literacy skills (Geva, 2000). This argument can be taken further to advance the notion that when literacy difficulties occur in the one language system of the bilingual, they are more likely to occur simultaneously in the other language system of the bilingual child.

There is some evidence to suggest that knowledge and skills acquired in the L1 can transfer to the L2 and facilitate the development of L2 literacy. Durgunoglu, Nagy, & Hancin-Bhatt (1993) conducted a correlational study with first grade Spanish-speaking children to this effect. Results showed that phonological awareness in Spanish and Spanish word recognition predicted word and word recognition in English. From their study, Durgunoglu et al concluded that:

A child who already knows how to read in L1 and who has a high level of phonological awareness in L1 is more likely to perform well on L2 word and pseudo-word recognition tests. In contrast, a child who has some L2 word recognition skills but low phono-logical awareness tends to perform poorly on L2 transfer tests. ( p. 462)

A similar cross-linguistic study by Cisero & Royer (1995) yielded similar results. Therefore, from the findings of such studies, it seems plausible to hypothesize that bilingual children transfer their phonological awareness from their L1 to their L2 during literacy development. Comeau et al (1999) provided further evidence of the cross-linguistic transfer of phonological awareness. Their study showed that this transfer can also be bi-directional. That is, L1 phonological awareness can transfer to L2 literacy development and L2 phonological awareness can transfer to L1 literacy development and, in so doing, facilitate the development of literacy between and within languages. More recently, Veii (2003) and Veii & Eveartt (2005) not only confirmed the findings of the previous studies alluded to above, but they also extended these findings by showing the reverse transfer of phonological awareness from L2 to L1 and how this reversed cross-linguistic transfer of phonological processing skills influences the development of literacy in both L1 and L2 in their cohorts. With empirical evidence for the transfer of phonological skills between and across languages to aid with literacy development between and within languages, an argument may be advanced that when phonological awareness fails in either language, literacy development may fail in both languages.

Furthermore, studies by (Cummins, 1991) and (Bialystok, 1997) have shown that some cognitive and linguistic skills and knowledge also do transfer between languages even if they differ orthographically (e.g. Japanese and English and Chinese and English). That is, decoding skills in dissimilar orthographies do correlate positively, and children’s L2 literacy skills can be predicted from similar skills developed in the L1 (Verhoeven & Aarts, 1998). Similarly, L1 literacy and L2 literacy also correlate positively; as such, L1 literacy could also be predicted from L2 literacy (Veii, 2003; Veii & Everatt, 2005). Thus, underlying cognitive and linguistic processing skills such as phonological skills, memory, orthographic processing skills, and the speed of processing, can somehow predict individual differences in the development of decoding skills in both L1 and L2 (Geva & Wade-Woolley, 1998).

On the basis of these findings, it may suffice to say that cross-transfer of phonological processing skills seems to support bilingual children develop L2 literacy faster and perhaps earlier than they otherwise would have. The empirical evidence presented confirms the benefits that L2 literacy development accrues from developing, strengthening, and consolidating L1 skills. This observation may further strengthen the case for the likely occurrence of literacy difficulties in both language systems of the bilingual, for L2 literacy skills may not develop optimally if L1 language skills are not fully developed. Similarly, literacy skills in one language (e.g. L2) may also fail to develop if L1 literacy fails to develop.

Research aims

The aims of the single case analyses reported in this chapter were (1) to identify cognitive and linguistic factors that may be related to potential literacy difficulties in this cohort of bilingual children in both their L1 (Herero) and L2 (English), (2) to identify potential cases of "differential dyslexia" in this cohort of bilingual children and (3) to assess the assumptions of the central processing hypothesis and the script dependent/orthographic depth hypothesis with regard to literacy development and difficulties. From the point of view of the central processing hypothesis, literacy difficulties arise when a child has defective underlying cognitive and linguistic skills common in all languages. In contrast, the script dependent/orthographic depth hypothesis states that the depth of the orthography determines the pattern and the severity of literacy difficulties. Thus, the question this study attempted to answer is whether the degree of transparency or defective cognitive-linguistic processing skills of Herero and English will influence the patterns and severity of literacy difficulties in these two languages among the Herero-English bilingual school children and, ultimately, determine whether or not literacy difficulties would occur in Herero or in English or in both Herero and English.

ethods

Research Participants

The original sample, from which the five cases of literacy difficulties reported here were selected, consisted of 117 children in Grades 2-5 selected from three Namibian elementary schools, one rural and three urban. The children ranged in ages between 7 and 12 years. The children were studied in their course of literacy development in Herero and English over a two-year period; particularly investigating possible predictors of literacy development in Herero (L1) and English (L2) among a number of measures of cognitive/linguistic processes. Specifically, the five single cases were selected from the original sample of grade 3 children for whom data were available at Time 1 and Time 2 of testing. These children were selected to provide information about the development of literacy over the course of the study as well as to ensure that the child had experienced at least one year of literacy teaching prior to initial testing.

Selection Procedures

The cases that constituted a sample for the analysis of literacy difficulties were selected on the basis of the following criteria:

- Grade:

Cases for the analyses of literacy difficulties were selected from Grade 4. The rationale for selecting this grade was that at this stage the children would have had at least two years of formal literacy instruction in both Herero and English. For diagnostic purposes, this grade would allow the researcher to identify those children who are at least two years behind in reading and writing skills in either language.

- Availability of data at time 1 and time 2:

Potential cases of literacy difficulties had to have data at both times 1 and 2.

- Availability of data on particular measures:

To be selected, the children in this grade had to have data on literacy measures in both Herero and English, listening comprehension measures in both languages, and on measures of general non-verbal reasoning at time 1 and time 2. Hence, all cases with missing data at both times 1 and 2 were excluded; thus, reducing the pool from which children with potential literacy difficulties would be selected to 30 children.

- Poor literacy at time 1 and time 2:

From these 30 children those that showed poor literacy skills either at time 1 or time 2 in either language were selected. This reduced the sample to 8 cases.

- Selection of five cases for detailed discussion based on potential categories of difficulties: From these 8 cases, five cases that presented with literacy difficulties in both languages were selected. These cases are representative of the following four categories of literacy difficulties:

- iteracy difficulties related to non-verbal reasoning deficits;

- language-based literacy difficulties;

- persistent literacy difficulties in L1 and L2

- persistent literacy difficulties in L2

Measures/tests used

Measures used for this study included measures of word reading, decoding, phonological awareness, verbal and spatial memory, rapid naming, semantic fluency, sound discrimination, listening comprehension, and non-verbal reasoning (for a detailed description of these measures the reader is referred to Veii & Everatt (2005)) Herero and English versions of tests were developed for use with the cohort tested. For most measures, cross-language adaptations were necessary and performed by native speakers of both languages who were familiar with current work in literacy teaching/assessment in Namibia. For non-verbal measures, only the instructions needed to be in both languages; however, for the remaining tests, different Herero and English materials were required. These materials were designed to test the ability targeted by the measure. For example, tests that measured the ability to recognize phonemes required items with the same beginning and items with the same end sounds. Tests were also designed to be appropriate culturally to the children tested – e.g., line drawings in the rapid naming task should be familiar to the children tested. Pilot work and consultation with teachers ensured that items were appropriate for the cohort tested. The primary concern of test development was appropriate levels of familiarity with materials, rather than controlling for factors such as word length and structure. Hence items were based on reading lists taken from graded text books and were not matched across languages in terms of numbers of letters or sounds within words. As recognized by Geva and Siegel (2000), it is often impossible to design parallel tests in two different languages that are matched along a variety of dimensions such as word length, word frequency, syllabic length and structure. This is particularly the case when comparing a language with predominantly one and two syllable words (English) with a language where three or more syllables are the norm (Herero). However, the lack of ability to control for these phonological-based factors across languages needs to be acknowledged by this study (for details of word and non-word materials, please refer to Veii & Everatt (2005)).

Testing Procedures

Children were tested individually during school hours. Assessments were divided into Herero and English sessions. Each of the sessions took two days to complete and lasted approximately 40 minutes per day. Testing of each child was performed over a four day period to allow rest periods. Herero testing was completed prior to testing in English. All data were collected within a four month period.

Data Analysis

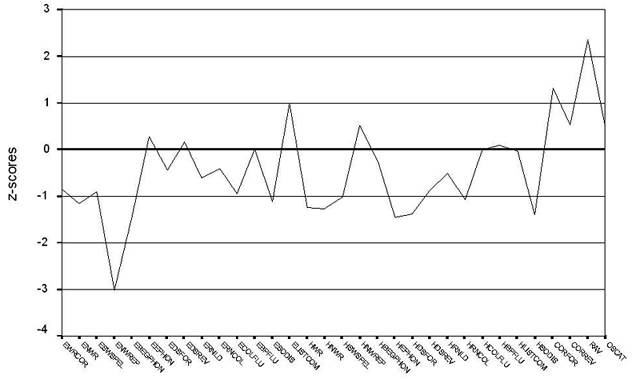

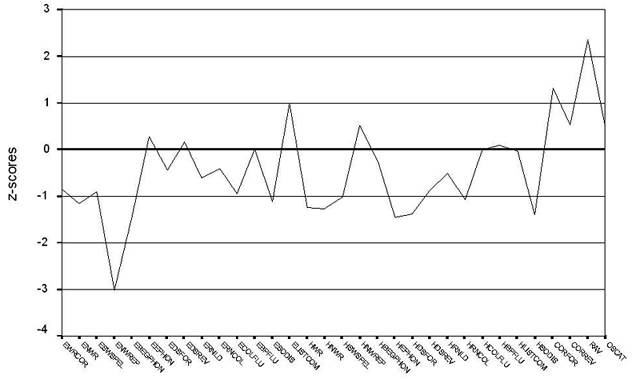

For the purposes of comparison across measures, test scores were transformed to z-scores. For each single case, z-scores were calculated by taking the difference between the single case’s score on a test and the average of their year group and dividing by the standard deviation of the year group. Differences were calculated such that a negative value always indicated a poor performance in comparison to the year group. Therefore, for each test, a single case is represented by the number of standard deviations that their score differs from the average for their year group. These data were then presented graphically to show the profile of performance of the cases selected.

For each graph, on the x-axis of each graph lie the measures used, and on the y-axis are the levels of skills acquired on each measure based on the z-scores. The mean, or average (z = 0) for each of the measures, is indicated by a heavy black line. Scores within the range of 1 or –1 represent the average range for the grade from which the single case was selected. Thus, if a given child obtains a score below –1, his/her ability in that specific measure is considered to be worse than the average range of abilities for his/her grade. Consequently, a specific deficit in that particular skill may be identified. The tasks are labeled in the same abbreviated manner on all graphs. Note, however, that not all the measures that were used at Time 1 were used at Time 2. Those that were used at Time 1 and Time 2 are abbreviated in the same manner, although the digit 2 has been added to the end of a label to denote that the score is derived from testing at Time 2. Labels are described in Table 1 below:

Table 1 .Legends for the graphs showing single case profiles at Time 1.

Abbreviated Labels |

Tasks |

Abbreviated Labels |

Tasks |

EWR |

English word reading |

HWR |

Herero word reading |

ENWR |

English non-word reading |

HNWR |

Herero non-word reading |

ESWSPEL |

English single word spelling |

HSWSPEL |

Herero single word spelling |

ENWREP |

English non-word repetition |

HNWREP |

Herero non-word repetition |

EBEGPHON |

English beginning phoneme |

HBEGPHON |

Herero beginning phoneme |

EEPHON |

English ending phoneme |

HEPHON |

Herero ending phoneme |

EDSFOR |

English digit span forward |

HDSFOR |

Herero forward digit span |

EDSREV |

English digit span reverse |

HDSREV |

Herero reverse digit span |

ERNLD |

English rapid naming of line drawings |

HRNLD |

Herero rapid naming of line drawings |

ERNCOL |

English rapid naming of colors |

HRNCOL |

Herero rapid naming of colors |

ECOLFLU |

English color semantic fluency |

HCOLFLU |

Herero color semantic fluency |

EBPFLU |

English body parts semantic fluency |

HBPFLU |

Herero body parts semantic fluency |

ESODIS |

English sound discrimination |

HSODIS |

Herero sound discrimination |

ELISTCOM |

English listening comprehension |

HLISTCOM |

Herero listening comprehension |

RAV |

Ravens’ Progressive Matrices |

CORFOR |

Forward spatial span (forward corsi blocks) |

OSCAT |

Object semantic categorization |

CORREV |

Reverse spatial span (reverse corsi blocks) |

Results

Identification of single cases of severe literacy difficulties

Five single cases that presented evidence of literacy difficulties were selected for discussion. These cases were representative of the four different categories of literacy difficulties identified. A description of the nature of the literacy difficulties each case presents is given below.

Literacy Related to Non-verbal Reasoning Deficits

The case presented in this category describes a child with evidence of literacy difficulties that may be based on deficits in non-verbal reasoning.

Case 52:

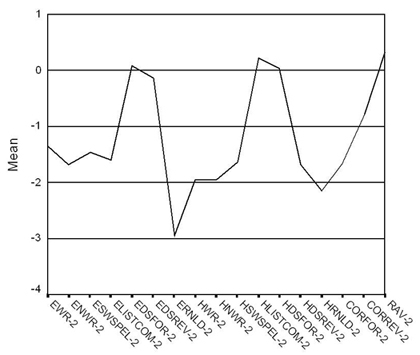

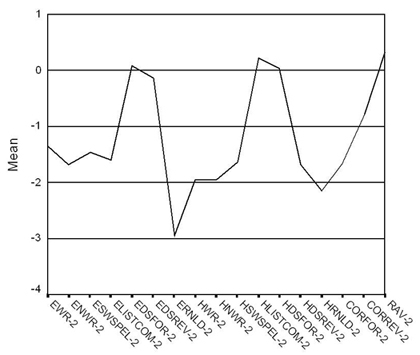

Case 52 is a 10-year old boy at the Omatjete Primary School who presented evidence of persistent difficulty in measures of non-verbal reasoning (Raven’s Progressive Matrices), which may be indicative of deficits in general intellectual functioning. There seems to be further evidence of more deficits in semantic fluency, which may reflect this child’s poor vocabulary in both Herero and English (see Graph 1). His general language comprehension seems to be within the average range. However, the deficits seem to have an impact on his literacy skills in both languages, particularly at time 2 (see Graph 2).

Graph 1. Cognitive, linguistic and literacy profiles of Child 52 at time 1.

Graph 2. Cognitive, linguistic, and literacy profiles of Child 52 at time 2.

Language-based Literacy Difficulties

The case presented in this category describes a child with evidence of language comprehension problems in both Herero and English.

Case 85:

Case 85 is a 9-year old girl from Omatjete P.S. who presented with evidence of poor performance on both listening comprehension measures, which may be indicative of a general language comprehension deficit. These deficits are apparent despite her general reasoning and non-verbal abilities appearing to be within the average range. However, at time 1, these comprehension deficits seem to have only a slight impact upon her literacy skills in both Herero and English. Indeed, her performance on the Herero literacy measures seems typical of her peer group (see Graph 3).

By time 2, however, there is some evidence of literacy difficulties, but these are confined to English Word Reading (see Graph 4) and the problems with listening comprehension also seem to be restricted to English (the second language). These L2 literacy deficits may be attributed to the fact that Case 85’s L2 proficiency is still not well developed, or is still developing. According to Cummins (1984), sufficient second language skills may take anywhere from five to seven years to come to fruition before literacy skills, particularly in the L2, can be evaluated. Thus, Case 52’s current linguistic profile may be an epitome of Cummins’ argument and may be an example of transitory literacy difficulties that may improve with time and sufficient educational experiences, i.e. when L2 language ability increases, L2 literacy would also be expected to grow. It may be concluded that R.Z. problems are transitory and with time and proper educational experiences, may improve.

Graph 3.Cognitive, linguistic, and literacy profiles of Child 85 at Time 1.

Graph 4. Cognitive, linguistic, and literacy profiles of Child 85 at Time 2

Persistent Literacy Difficulties in L1 and L2

This category describes two children who seem to present with persistent literacy difficulties in both L1 and L2. For one child, the literacy difficulties may be accompanied by deficits in semantic fluency in both Herero (L1) and English (L2), verbal memory and language comprehension in L2 and an inability to process a sequence of novel sounds in L1. For the other child, the literacy difficulties seem to be coupled with problems in phonological processing in L2 and deficits in non-verbal memory skills.

Case 114:

Case 114 is an 8-year old boy at the Okakarara Primary School who presented with evidence of poor performance on measures of semantic fluency in both Herero and English, which may be indicative of an underdeveloped vocabulary in both languages. At the same time, K.K. also presents with poor performance in L2 verbal working memory and in L1 ability to repeat a sequence of nonwords. These deficits appear to impact more upon L1 literacy skills, particularly on decoding and reading skills at time1 (see Graph 5).

By time 2, however, K.K.’s literacy difficulties do not remain confined to L1 only, but extend to both L1 and L2 literacy skills, with L2 language comprehension problems possibly contributing to this persistent difficulty with literacy (see Graph 6).

Graph 5.Cognitive, linguistic, and literacy profiles of Child 114 at Time 1

Graph 6.Cognitive, linguistic, and literacy profiles of Child 114 at Time 2.

Case 103:

Case 103 is an 11-year old girl attending the Okakarara Primary School who seems to present with evidence of deficits in L2 phonological processing skills and L2 and L1 verbal memory. These deficits may be indicative of deficient phonological processing and working memory skills. Her non-verbal reasoning skills seem to be within the average range. The deficits, however, seem to have an impact on Case 103’s literacy skills in both Herero and English at time 1 (see Graph 7). By time 2, there continues to be evidence of literacy difficulties in both L1 and L2, with deficits in L2 verbal memory skills and in non-verbal memory skills still persisting at this time (see Graph 8). The L2 phonological deficits, deficits in L1 and L2 working memory, and deficient non-verbal memory skill all seem to combine in contaminating and cross-contaminating both L1 and L2 literacy skills.

Graph 7.Cognitive, linguistic, and literacy profiles of Child 103 at Time 1.

Graph 8.Cognitive, linguistic, and literacy profiles of Child 103 at time 2

Persistent Literacy Difficulties in L2

This category describes a child who shows persistent literacy difficulties in L2.

Case 86:

Case 86 is a 12-year old boy attending the Omatjete Primary School. His listening comprehension skills in both Herero and English and his non-verbal general reasoning skills are well within and above average. At the same time, however, E.Z. presents with deficient sound discrimination skills in the L1 and L2 and deficits in L1 phonological processing skills, phonological access to items, and verbal as well as non-verbal memory skills. These deficits seem to have an impact on his literacy skills in both Herero and English at time 1 (see Graph 9). By time 2, however, there is still evidence of literacy difficulties being confined to L2 only. Similarly, the language listening comprehension problems that arise at time 2 also seem to be confined to L2 only (see Graph 10).

Graph 9.Cognitive, linguistic, and literacy profiles of Child 86 at Time 1.

Graph 10. Cognitive, linguistic, and literacy profiles of Child 86 at Time 2.

General findings

The evidence provided in this chapter seems to suggest slightly mixed results regarding literacy difficulties, or differential dyslexia. Out of the five cases of literacy difficulties presented here, two (cases 85 and 86) seemed to experience persistent difficulties in L2 literacy, thereby confirming the views of the script-dependent hypothesis (that literacy development in less transparent orthographies is delayed and that literacy difficulties are more pronounced). However, these L2 literacy difficulties may be related to poor L2 language skills, especially in the case of Case 85, which in turn, may be related to the fact that this cohort could be considered, by Namibian standards, to still be in the early stages of L2 and L2 literacy development. Hence, it can be argued that the L2 literacy difficulties they experience may not be genuine but transitional and, as such, may be overcome with time and proper literacy instructions. However, it is evident that literacy difficulties are present in both Herero and English at Time 1 of testing.

The rest of the cases discussed here seem to present with literacy difficulties in both languages, indicating that if literacy difficulties occur in one language, they are also likely to occur in the other, consistent with the views of the central processing hypothesis. But given that the two languages studied here vary in their orthographic depth one would perhaps expect the patterns of the literacy difficulties to vary accordingly, with more severe literacy difficulties occurring in English, the less transparent orthography than in Herero, the more transparent orthography. However, the prevalence of literacy difficulties seen here seems to be similar along the assessed cognitive-linguistic measures in both Herero and English. The cognitive-linguistic factors that seem to be related to literacy difficulties in Herero seem to be the same in English literacy difficulties as well. For example, verbal (phonological) memory, sound discrimination, semantic fluency and rapid naming occur simultaneously in both Herero and English as the underlying cognitive-linguistic factors that may be related to literacy difficulties in either language in the majority of the cases, even in those cases with persistent literacy difficulties in L2 only. Other factors such as phonological processing skills and nonword repetition occur alternately in the one or the other language. As a result, and applying the findings that L1 and L2 phonological processing skills can transfer across and within languages, the "cross-contamination" of literacy across rather than with-in languages witnessed here may be attributed to deficient cognitive-linguistic skills with which the children present in the one or the other language.

Of great importance here is the observation that the same cognitive-linguistic factors seem to be related to literacy difficulties in both languages. Thus, on the basis of the presented evidence, and despite the differences in their orthographic depth, Herero and English seem to place more or less the same degree of cognitive demands on the three single cases presented in this study because, what the children seem unable to process in one language they also seem unable to process in the other. Simply put, the differences in the orthographic depth of Herero and English do not seem to matter in influencing literacy difficulties in this group of children. However, this finding cannot be said to be conclusive until further research can confirm it.

Discussion

This part of the research project continued to test the validity of the central processing and script dependent/orthographic depth hypotheses. The overall study (Veii, 2003; Veii & Everatt, 2005) predicted that those children with defective cognitive and linguistic processing skills were more than likely to experience literacy difficulties in both Herero and English (central processing hypothesis). The hypothesis went on to state that literacy difficulties were more likely to be more severe in English, the less transparent orthography, than in Herero, which has a highly transparent orthography. The five cases of children presenting with literacy difficulties described here appear to have deficiencies in the key areas associated with the development of literacy and literacy difficulties, namely, phonological awareness, verbal short-term memory, rapid naming, and repetition. As such, these findings seem to provide evidence for the central processing hypothesis that literacy difficulties are a function of deficient underlying cognitive and linguistic processing skills. However, the findings (Cases 85 and 86) also lend credence to the script-dependent hypothesis in that when these two children presented with L1 and L2 literacy difficulties at Time 1, by Time 2 only L2 literacy difficulties still persisted, confirming the view that literacy in less transparent orthographies takes longer to develop and are more severe. Therefore, the findings of this study reaffirm Gholamin & Geva (1999) and Geva & Siegel’s (2000) conclusion that rather than being contradictory, the script-dependent and central processing hypotheses are complementary.

These skill areas in which the children in this study show deficiencies constitute various phonological processes and, weakness in them might be indicative of these children’s inability to establish new phonological representations. Thus, all of the five cases that exhibited poor literacy skills were those that differed from the good readers on the basis of cognitive and linguistic processing skills which influence the development of literacy. In turn, this implies that individual differences in these skill areas are indeed indicative of difficulty in developing literacy difficulties not only in the L1 but in L2 as well. Owing to this, it is possible that literacy difficulties in these children, and perhaps in other L2 children in Namibia, may be identified early using the same cognitive and linguistic measures designed for English L1 monolingual school children even before they develop proficiency in their second language (Everatt, Warner, & Miles, 1997; Hutchinson, Whitely, & Smith, 1997; Geva, 2000). Furthermore, utilizing these measures might be likely to minimize over-identification and under-identification of literacy disabilities and other learning disabilities among L2 users such as Namibian bilingual school children.

All of the five children who make up the cases with literacy difficulties showed deficient phonological awareness in the L1, L2 or both L1 and the L2. Given that phonological awareness is transferable between languages, and as such influences the development of literacy across languages, it may be plausible to argue that poor phonological awareness in one language might curtail the development of literacy in another language. Thus, deficient L1 phonological awareness, as is presented in these cases, may have negatively affected literacy development in the L2 and vice versa.

As Scarborough (1998) has shown, verbal short-term memory has been found to be deficient in many reading disabled children, although not necessarily all the time. Disabled readers remember fewer verbal items than expected for their age. On the other hand, they show normal memory span for visual information (Snowling, 2000). Disabled readers’ memory impairment is attributable to impaired representations of the phonological forms of words, which in turn, limits the number of verbal items disabled readers can retain in their memory (Snowling, 2000). Consequently, this affects their working memory such that remembering the sequence of sounds that can be coupled together to form a word becomes difficult. In this way, the eventual effect is that reading is also affected. As can be seen from these cases, all the children who showed deficiencies in verbal working memory in either L1 or l2 also showed poor literacy skills in either language. At the same time, although fewer children showed poor visual information processing skills, the majority also showed strong skills for processing visual information, as is reflected in their performance on the spatial span (CORSI blocks) tasks, particularly at time 1. Thus, these results may confirm previous findings that disabled readers have difficulty with verbal short-term memory but not with information requiring visual memory span.

According to Wolf, Bally, & Morris (1986), disabled readers, or dyslexics, are slower than same-age normal readers in completing tasks requiring naming familiar objects under timed conditions. The majority of children who presented with literacy difficulties in this study also presented with deficits in rapid naming of objects they were expected to be familiar with. Again, this study may further confirm earlier findings that disabled readers are slow at naming familiar objects. The slowed rate of naming familiar objects can slow down the rate at which these children can read at both the word and sentence levels. They may be slow in automating their reading process, thereby heavily influencing their reading (Bowers & Wolf, 1993) and eventually, the comprehension of what they read. The co-occurrence of phonological awareness deficits with rapid naming deficits in some of these children may spell more severe literacy difficulties for them as a result of a "double-deficit" in both their naming speed and their phonological processing skills.

Dyslexic children show difficulty with the processes of speech production. Earlier, Snowling (1981) had shown that dyslexic children four years older than their controls had difficulty repeating non-words, but not with the repetition of words. At least three of the five children with literacy difficulties in this study also exhibited difficulty with repeating strings of non-words. This finding seems to have confirmed previous findings that children with reading problems do indeed experience difficulties with the repetition of words unfamiliar to them, or with make-up words. The inability to repeat non-words may indicate that the critically important phonological processes that are necessary for the ability to repeat non-words or unfamiliar words may be impaired, and therefore possibly lead to the literacy difficulties these children seem to experience. According to Snowling (2000), defective skills in processing non-words or unfamiliar words can have long-term effects on the nature of the lexical representations that disabled readers can build for words. All aspects of retrieving words can be affected by this inability. This being the case, it is plausible that these children are likely to have difficulty with a whole range of activities that involve word and/or name retrieval and therefore, literacy in general.

At least two of these four children are in their early teens (12 and 13 years old respectively) and are still in primary school. This is obviously a serious delay in progressing through the educational system that may be attributed to the literacy difficulties these children seem to experience. While teachers and parents may be wondering as to what causes this delay, the answer, or part thereof, may lie in the cognitive-linguistic deficiencies these children seem to present. Therefore, it is probably no wonder these children are still in elementary school. The ability to read and write forms the foundation of education. Without these two skills, higher levels of education become difficult if not totally impossible to attain. These children, and many others in Namibian schools who encounter literacy problems, are an example of what happens when literacy fails to develop either due to lack of proper educational opportunities or genuine cognitive and linguistic deficits. Of course, the particular child with literacy problems ends up being the most disadvantaged victim of an educational system that does not have the capability (probably due to a lack of financial or human resources or both) to provide the necessary and relevant services to children with special educational needs.

One of the objectives of this research project was to identify those factors that may predict the development and failure of literacy skills among Namibian school children. This objective may have been achieved, or at least, this study may have laid the foundation for identifying these problems. Furthermore, it is hoped that the cognitive and linguistic factors that may be related to the literacy difficulties these children seem to present with will become part of the arsenal of tools authorities and all others involved in the delivery of special educational services will use in delivering the right kind of special educational services to those children who need them the most. Of course, further research with Namibian children of the other language groups not included in this study is necessary to confirm with a higher degree of certainty the role these cognitive and linguistic processing skills play in the development of literacy across the various Namibian language groups.

© Kazuvire R. H. Veii (University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia)

REFERENCES

Bialystok, E. (1997). Effects of bilingualism and biliteracy on children’s emerging concept of print. Developmental Psychology, 33 (3), 429-440.

Bowers, P.G., & Wolf, M. (1993). Theoretical links among naming speed, precise timing mechanisms and orthographic skills in dyslexia. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 5 (1), 69-85.

Cisero, C. A. & Royer, J. (1995). The development and cross-language transfer of phonological awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 20, 275-303.

Comeau, L., Cormier, P., Grandmaison, E. & Lacroix, D. (1999). A longitudinal study of phonological processing skills in children learning to read in a second language. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91 (1), 29-43.

Cummins, J. (1991). Interdepenence of first-and second language proficiency in bilingual children. In E. Bialystok (Ed.), Language processing in bilingual children (pp. 70-89). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Durgunoglu, A. Y., Nagy, W. E., & Hancin-Bhatt (1993). Cross-language transfer of phonological awareness. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85 (3), 453-465.

Everatt, J., Warner, J., & Miles, T.R. (1997). The incidence of Stroop interference in dyslexia. Dyslexia, 3, 222-228.

Everatt, J, Smythe, I. Ocampo, D & Veii, K (2002). Dyslexia assessment of the bi-scriptal reader. Topics in Language Disorders, 22, 32-45.

Geva, E. (2000). Issues in the assessment of reading disabilities in L2 children - Beliefs and research evidence. Dyslexia, 6, 13-28

Geva, E., Wade-Woolley, L. ( 1998). Component processes in becoming English-Hebrew biliterate. In A. Y. Durgunoglu and L. Verhoeven (Eds.), Literacy development in a multilingual context: Cross-cultural perspectives, (pp. 85-110). Mawhaw, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Geva, E, & Siegel, L. S. (2000). Orthographic and cognitive factors in the concurrent development of basic reading in two languages. Reading and Writing : An Interdisciplinary Journal, 12, 1-30.

Gholamain, E. & Geva, E. (1999). Orthographic and cognitive factors on the concurrent development of basic reading skills in English and Persian. Language Learning, 49, (2), 183-217.

Hutchinson, J., Whitley, H., & Smith, C. 91997). Literacy development in emergent bilingual children. In L. Peer & G. Reid (Eds.), Multilingualism, literacy, and dyslexia: A challenge for educators (pp. 45-51). London: David Fulton Publishers.

Kline, C. & Lee, N. (1972). A transcultural study of dyslexia: Analysis of language disabilities in 277 Chinese children simultaneously learning to read and write in English and Chinese. Journal of Special Education, 6, 9-26.

Leker, R. R & Biran, I. (1999). Unidirectional dyslexia in a polyglot. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 66, 517-519.

Miller-Guron, L & Lundberg, I (2000). Dyslexia and second language reading: A second bite at the apple? Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 12, 41-61.

Ocampo, D. (2002). Effects of bilingualism on literacy development. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Surrey, United Kingdom.

Scarborough, H .S. (1998). Prediction of reading disability from familial and individual differences. Journal of educational Psychology, 81, 101-108.

Smythe, I. & Everatt, J. (2002). Dyslexia and the multilingual child: Policy into practice. Topics in Language Disorders, 22 (5): 71-80.

Smythe, I. (2002). Cognitive factors underlying reading and spelling difficulties: A cross-linguistic study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Surrey, United Kingdom.

Snowling, M. (1981). Phonemic deficits in developmental dyslexia. Psychological Research, 43, 219-234.

Snowling, M. (2000). Dyslexia. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Limited.

Veii, K. R. H. (2003). Cognitive and linguistic predictors of literacy in Namibian Herero-English bilingual school children. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Surrey, United Kingdom

Veii, K. & Everatt, J. (2005). Predictors of reading among Herero-English bilingual Namibian school children. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 8 (3), 239-254.

Verhoeven, L. & Aarts, R. (1998). Attaining functional biliteracy in the Netherlands. In A. Y. Durgunoglu and L. Verhoeven (Eds.), Literacy development in a multilingual context: Cross-cultural perspectives (pp.111-133). Mawhaw, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wolf, M., Bally, H., & Morris, R. (1986). Automaticity, retrieval processes, and reading: A longitudinal study in average and impaired readers. Child Development, 55, 988-1000.

Wydell, T. N. & Butterworth, B. (1999). An English-Japanese bilingual with monolingual dyslexia, Cognition, 70, 273-305.

Acknowledgement: The work performed as part of this paper was supported by a grant awarded by the University of Namibia Research and Publications Committee for the author’s doctoral research. Air Namibia supported travelling to Vienna, Austria to present the findings of this study as a paper at the IRICS Conference held in December 2005. The author would like to thank the editor(s) and referee(s) of the IRICS Conference Publications.

8.3. Innovation and Reproduction in Black Cultures and Societies: A comparative Dialogue and Lessons for the Future

Sektionsgruppen

| Section Groups

| Groupes de sections

Inhalt | Table of Contents | Contenu 16 Nr.

Inhalt | Table of Contents | Contenu 16 Nr.

For quotation purposes:

Kazuvire R. H. Veii (Department of Psychology, University of Namibia, Windhoek, Namibia): Innovations and Developments in Psychology and Education: Do Literacy Difficulties in Namibian Herero-English Bilingual School Children Occur in One or Both Languages? In: TRANS.

Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften. No. 16/2005.

WWW: http://www.inst.at/trans/16Nr/08_3/veii16.htm

Webmeister: Peter

R. Horn last change: 14.4.2006