Nr. 18 Juni 2011 TRANS: Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften

Section | Sektion: Signs and the City. In honor of Jeff Bernard

Gotham City: Medieval signs of Modernity

The representation of American urban life in Batman-comics

Roland Graf (University of Applied Sciences, Sankt Poelten/Austria) [BIO]

Email: lbgraf@fh-stpoelten.ac.at

Konferenzdokumentation | Conference publication

Abstract:

Like many other scenes of popular comics, Gotham City cannot be found on the US map. Nevertheless Batman’s hometown offers Semiotic resemblances with a lot of existing towns, regardless of its fictional and special character in the world of comic books.

Recently a monography on city-architecture listed up 28 different aspects of urbanity (cf. Lampugnani 2010). Most of them were linked with a certain utopian or ideological purpose, how the life of the masses should be organized in built structures. The role of urban landscapes in Batman-storylines quite differs from that optimism: Gotham, an eccentric town in Lotman’s sense, has always had its dysfunctions, that will be examined by a closer look at two important and unusually long Batman storylines.

Introduction

With the New York Herald publishing Winsor McCay’s adventures of Little Nemo, comics became an urban art form also in their rhetoric quality. Of course most readers in those early days lived in cities and the only media containing comics were the American newspapers published in NYC, Chicago and so on. McCay was not simply showing a sequence of motions in time in his drawings, but tried to show as much parallel action as possible in one picture (Peeters 2003: 68). His exploration of the artistic possibilities of the young medium led him into using the whole broadsheet of the Herald. Soon he discovered synchronicity as an alternative to sequences(1). His innovation should not be underestimated; the vertical picture of the city offered the public a completely new perspective in a time when flight and film were still young. To a certain extent the first representation of the city in its vertical dimension was done in Little Nemo, when the sleepwalking hero went through the city as a giant, eye to eye with the skyscrapers. Compared to the etchings of cities still popular in Europe in the late 19th Century, this American way of portraying cities contained a new visual dimension.

Historically, the cities’ architecture changed in the last 100 years, but comics in their narrative possibilities did not to the same extent. We still have the sequential narrative and a realistic setting, when we look at the superhero genre. If Thomas Inge is right and the “serious study of comics […] may be a central element in our understanding of postmodern civilization” (Inge 1995: 32), then a closer look at the city as an endangered environment in the drawn version and a hotspot of modern living should be of quite an interest. As an essay on the “city in comics” at any rate has to be ecclectical, I will concentrate on some architectural details only to examine, how urbanity is shown in one of the most prominent examples of the US superhero tales, Bob Kane’s Batman.

Capital Sins – The Archetypical City

Allegorical cities in comic books like Metropolis (Superman), Star City (Green Arrow) and of course Gotham City offer all the narrative possibilities, real places would lack, when it comes to escapism: It is easier to imagine, those colorful adventures are happening some place, we know, but can never go to – the literal depiction of an utopia(2) – than to compare every detail with a concrete city. The topography of US comics and animated films knows a lot of towns that should not be located – Springfield (Simpsons), Duckburg (Donald Duck) – and some which are only vaguely positioned in a certain state as Smallville, Kansas, where Superman grew up, or South Park, Colorado. Gotham belongs to the first category, giving the city a more archetypical outlook. Although there are a lot of real places mentioned and shown (e.g. in the “Mr. Wayne goes to Washington” storyline 1998), the readers are never shown, where the city is located. Even a map of the city is seldom used in the narrative(3).

The first semiotic observation concerning cities always concentrates on their site, as this is also visible in a two-dimensional picture (e. g. on a coin). The “eternal city” Rome was not by chance situated and especially present in iconography on top of seven hills. As a phare of the Roman Empire and later Christianity it dominated the flat land surrounding the capital. Eccentric cities, as Yuri Lotman coined the term (Lotman 2000: 192), are dominated by their position at the margin of nature and culture. Those towns are situated at the edge of culture and can be “interpreted either as the victory of reason over the elements, or as a perversion of the natural order” (Lotman 2000: 192). His observation of the myths and symbols used for describing St. Petersburg, a real, but artificial city in his view, can easily be transferred to any fictional city.

In this sense, Gotham is eccentric, as allegories of natural and rural origin are frequently presented as a threat to the city. To name just a few, villains include Poison Ivy, bringing orgiastic green jungles to town; the amorph Clayface; Mister Freeze, eager to transform Gotham to a glacier; or the Bayou-born Killer Croc and Swamp Thing. Even the Scarecrow, the disguise of Jonathan Crane, cannot hide the bucolic side of this “Professor turned madman” character. Crane, as a former lecturer on psychology, is on the surface because of his own past and the means of his choice (mostly toxic gas) an urban figure. On the iconic layer however, he shows a most rural menace walking around in Gotham. Sometimes the menace to the structured world of the American city even gets an openly rural “address”; in “Workin’ My Way Back to You”, an impressive episode without any dialogue, the readers spot the sign “Leaving Houma La.” (Dixon/Gecko 1996: 31), when Killer Croc is fleeing a Louisiana hunting crew.

Skyscrapers – The Vertical City

Unlike other superheroes’ hometowns, Gotham is often shown from above. Whereas flying superheroes like Thor or Superman are either battling in the air or on the ground, Batman often looks out for the villains from above. People falling from rooftops, penthouses, fire-escapes and – most iconic – the hero waiting amidst gargoyles are part of this vertical urban sign-system. In “Assembly”, a storyline uniting Batman and his sidekicks during the aftermath of the earthquake in Gotham (Rucka/Deodato/Parsons), scenes switch only between rooms and rooftops, the city as a whole is never present. The cover and the last page of that issue figures Batgirl, Huntress, Nightwing, Robin and – of course – Batman on top of a skyscraper.

The view from above, normally associated with birds of prey (most of the gargoyles Batman nestles on resemble birds or winged harpies) is unusually frequent not only in this storyline(4). Six out of twenty-two pages of Batman # 494 (Moench/Aparo/Mandrake 1993) show a fight on top of the police department, involving Commissioner James Gordon, serial killer Cornelius Stirk, the Joker, Scarecrow and Batman. In another episode of the same storyline, fifteen out of twenty-four pages are located on rooftops (Grant/Blevins/George 1993).

Gargoyles – The Roman(t)ic City

In “Batman 492” we are shown the hunt for an escaped madman from Arkham Asylum. The only named places the Mad Hatter visits are Tenniel Estate on the outskirts of town and Gotham Zoo (Moench/Breyfogle 1993 a). All three places are part of the medieval iconography in the city: stones and hand-cast iron, spires and shadows mark old Gotham. As the importance of (German) Romantic topoi in the Batman series already has been described in detail (Graf 2010), I will concentrate on the city’s dimensions, which also contribute to the dialectic between allusions of the archaic and the modern city. Of course, the reader of Batman stories is used to chivalry surviving in modern city-life, epitetha like Caped Crusader or Dark Knight are frequently used for the crimefighter. But there is also the small set of scenes in the Batman narrative, shrinking the US metropolis to a tiny conglomerate of places of action.

Two storylines strongly focus on Gotham as a city, showing lots of places or aspects during the narration: “Knightfall” (1993), has an exhausted Batman until he got paralyzed in his final fight; and “No Man’s Land” (1998), when the U.S. government evacuated Gotham and isolated those who chose to remain in the city. The “Knightfall” episodes, in which the greatest foes tried to bring the hero down, all showed a rather timeless and placeless urban scene. Only if it was required for logical reasons, e.g. when serial killer Mr. Zsasz takes a boarding school hostage, is the Bates School for Women named (Moench/Breyfogle 1993b). This is not limited to the buildings. Although the stories obviously show a lot of scenes in the streets, most locations remain anonymous. Readers are rarely told any street names. The “Front ST.” sign shown twice in the “Broken City” storyline (Azzarello/Risso 2004: 11) is a noteworthy exception. Only for metafictional purpose – the magazine celebrated its 650th issue – was there a more prominent display of a street name (“650th ST.”) on the cover of Batman (Winnick/Rattle/Ramos 2006). As a result, the locations therefore shrink to a small village’s size and get a mere symbolic meaning: readers see the zoo, the museum, the city hall etc…

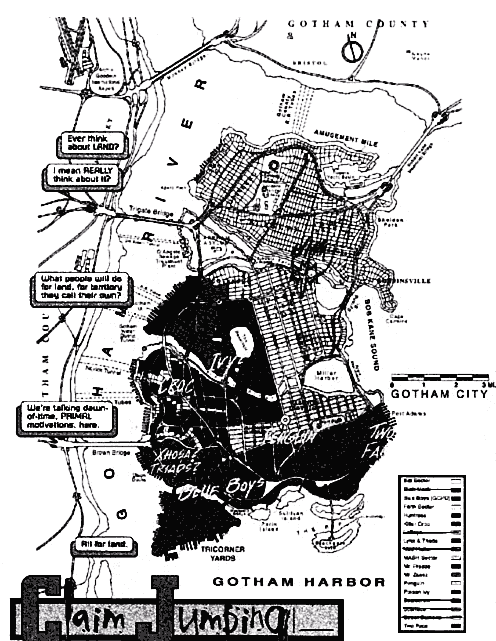

Fig.: Metafictional Map of Gotham City (Rucka/Deodato/Faucher 1999: 1)

Ghettos – The Mad City

The narrative cycle “No Man’s Land” seems suited best to illustrate the view of modern urban life in America as mirrored by the comics. After an earthquake, the city is abandoned by the authorities and anarchy takes over. In Batman’s words “Gotham has become feudal, tribal. A wasteland of petty baronies and fiefdoms. This is Gotham’s dark age. The old terrors of darkness and the night have been reborn, tugging on ancient, primal memories” (Edginton/D’Israeli 1999: 3). Interestingly enough these sociological remarks had been true even before, but not so visibly. For the first time readers are shown a city map of Gotham, where every district is controlled by the mob of one or another villain and central control (by the still remaining Gotham City Police Department) does not exist.

The rather detailed map appearing during “No Man’s Land” does not only show the districts. Self-referentiality, a semiotic concept present in comics “almost from the very beginning” (Inge 1995: 11) and rarely to be found in other Batman stories, shines through the map. “Bob Kane Sound” and the “Robert Kane Memorial Bridge” pay tribute to the inventor of Batman(5). Other editors, writers or comic artists like Frank Miller, Archie Goodwin, Neal Adams or Chuck Dixon have their own homages in the landscape. Like in other fictional texts we are suddenly “moved to ponder the nature of representation and the presence of the artful representer” (Alter 1975: 8).

The Future? The Surveillanced City

As “Batman is, above all, an information hound” (Zehr 2008: xvii), in most representations he prefers the predator’s position, preying on the badass’es false moves. That is the picture readers are accustomed to. But things have changes in recent narratives; the iconic picture of the hero on top of the spires of Gotham has been more frequently replaced by panels, showing the “dark detective” in a brooding mood looking at databanks and computers. The subtext of these pictures can be easily read: you have to control from within, not from above. There is not one angle of surveillance and justice any longer. Being away from the streets nowadays gives the heroes more perfect control over their cities. If we consider the press picture of the inner circle of President Obama’s cabinet while watching the deadly operation against Usama Bin Laden, we may get a glimpse of how (comic) art is still imitated by (the tragic of political) life.

References:

- Alter, Richard (1975). Partial Magic: The Novel as a Self-Conscious Genre. Berkeley: University of California Press

- Azzarello, Brian/Risso, Eduardo (2004). “Broken City” (= Batman # 624). New York: DC Comics

- Canemaker, John (1990). Winsor McCay, His Life and Art. New York: Abbeville Press

- Dixon, Chuck/Gecko, Gabriel (1996). “Workin’ My Way Back to You” (= The Batman Chronicles # 3). New York: DC Comics

- Edginton, Ian/D’Israeli (1999). “Bread and Circuses: 1” (= Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight # 117). New York: DC Comics

- Graf, Roland (2010). “Gothic Horror in Gotham City. Ängste im Superhelden-Comic” in: Walter Delabar/Frauke Schlieckau (Hg.) Bluescreen. Visionen, Träume, Albträume und Reflexionen des Phantastischen und Utopischen (= JUNI – Magazin für Literatur und Politik, 43/44); 78-86

- Grant, Alan/Blevins, Bret/George, Steve (1993). “The God of Fear” (= Shadow of the Bat #18). New York: DC Comics

- Grayson, Devin/Ryan, Paul (2000). “Bad Karma” (= Gotham Knights #3). New York: DC Comics

- Inge, Thomas M. (1995). Anything Can Happen in a Comic Strip: Centennial Reflections on an American Art Form. Columbus: Ohio State University Libraries

- Lampugnani, Vittorio Magnago (2010). Die Stadt im 20. Jahrhundert (two volumes). Berlin: Wagenbach

- Lotman, Yuri M. (2000). Universe of Mind. A Semiotic Theory of Culture. Bloomington/Indianapolis: Indiana University Press

- Moench, Doug/Breyfogle, Norm (1993a). “Knightfall # 1” (= Batman 492). New York: DC Comics

- Moench, Doug/Breyfogle, Norm (1993b). “Knightfall # 3” (= Batman 493). New York: DC Comics

- Moench, Doug/Aparo, Jim/Mandrake, Tom (1993). “Knightfall # 5” (= Batman 494). New York: DC Comics

- Peeters, Benôit (2003). Lire la bande dessinée. Paris: Flammarion

- Rucka, Greg/Deodato, Mike/Parsons, Sean (1999). “Assembly” (= Batman – Legends of the Dark Knight # 120). New York: DC Comics

- Winnick, Judd/Battle, Eric/Ramos, Rodney (2006). “All They Do Is Watch Us Kill” (= Batman #650). New York: DC Comics

- Zehr, Paul (2008). Becoming Batman. The Possibility of a Superhero. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press

Notes:

1 McCay also worked as a pioneer in animated films, which he abandoned too, once he thought his artistic input was done – for more details on him see Canemaker 1990. 2 Although this is no rule for superhero comics: New York City is the setting for “Punisher” and “Spider Man”, in which Peter Parker goes to Columbia University and his Aunt May lives in Queens. 3 One noteworthy exception will be discussed in detail in the paragraph “Ghettos – The Mad City” in this essay. 4 This iconicity is not limited to the comics; the film version Batman Begins (Christopher Nolan; 2005) ends with a dialogue between Lt. Gordon and Batman. Gordon characterizes the hero with the words “You’re wearing a mask and jumping off rooftops”. Of course they are standing on top of a police building during that closing scene. 5 Another reference is “Kane Avenue”, mentioned alongside “Robinson Park” and “Old Gotham” in an episode, starting with the robbery of a 7-Eleven store situated there (Grayson/Ryan 2000: 3).

Inhalt | Table of Contents Nr. 18

For quotation purposes:

Roland Graf: Gotham City: Medieval signs of Modernity The representation of American urban life in Batman-comics –

In: TRANS. Internet-Zeitschrift für Kulturwissenschaften. No. 18/2011.

WWW:http://www.inst.at/trans/18Nr/II-I/graf18.htm

Webmeister: Gerald Mach last change: 2011-06-17