Nahed Rajaa GHLAMALLAH

University of Oran 2 – Mohamed Ben Ahmed

Abstract:

Proficiency in language is essential to professional life, and teaching English as a Foreign Language tends to target more morpho-syntactic structures and lexical-semantic units than phonetic realisations. In Algeria, English is taught from Middle School to Secondary School for seven years, a period ranging between 750 and 830 hours. Whether learners have followed a literary or scientific stream, they reach university with an English pronunciation, upon which a Crosslinguistic Influence (CLI) from Standard Arabic, Colloquial Algerian Arabic, Berber and French could be depicted. In order to identify the validity of such a statement, the pronunciation of 80 first-year students was audiotaped at the English Department of Oran University 2. This paper discusses the findings of the conducted study so as to identify whether the informants’ repeated phonemic/phonetic deviations in English reveal an Algerian English pronunciation. The objective of this work is mainly to understand Algerian learners of English, to help them avoid unintelligibility and to investigate the linguistic aspects that may trigger a particular realisation instead of another.

Keywords: Crosslinguistic Influence, Language Acquisition, Phonetics, Phonology, Algeria

Résumé:

La maîtrise d’une langue est essentielle à la vie professionnelle, et l’enseignement de l’anglais comme langue étrangère cible beaucoup plus les structures morphosyntaxiques et les unités lexico-sémantiques que les règles phonologiques. En Algérie, l’anglais est enseigné à partir de l’école intermédiaire à l’école secondaire pendant sept ans, une période qui comprend entre 750 et 830 heures de cours. Lorsque les apprenants ont déjà suivi un cursus littéraire ou scientifique, ils arrivent généralement à l’université avec une prononciation anglaise, qui est nettement sujette à l’inter-influence linguistique de l’arabe standard, de l’arabe algérien colloquial, du berbère et du français. Afin d’identifier la validité de cette hypothèse, la prononciation de 80 étudiants de première année du Département d’anglais de l’Université d’Oran a été enregistrée. Cet article analyse les résultats de l’étude menée afin de répondre à la question suivante : est-ce que les déviations phonémiques et phonétiques répétées en anglais révèlent une prononciation algérienne de l’anglais. L’objectif de ce travail est principalement de comprendre les algériens apprenants de langue anglaise, de les aider à surmonter le risque d’inintelligibilité et d’étudier les aspects linguistiques qui provoquent une prononciation donnée.

Mots-clés: Apprentissage, Influence Inter-linguistique, Langue Anglaise, Phonétique, Phonologie, Algérie

-

Introduction

In Algeria, the perception some teenagers have of English may vary according to age, gender, level of education or field of interest. At school, English may represent the language of songs, movies, modernity and sciences. At university, however, English may express a means to success, job opportunities and openness to new horizons. Besides, there seems to be a change of attitude and aptitude towards English in social media platforms. During the last decade, there was also an emerging tendency to watch different Arabic channels on which shows and movies are broadcast in English. In addition to such an overview, English is becoming more and more attractive to the new Algerian generations, and that can be observed in clothes, advertisements, the names of shops and popular culture choices.

English in Algeria has a Foreign Language status. Becoming proficient in Standard English, a language abundantly and regularly enriched with neologisms, remains a considerable task. Learners need to develop their skills in speaking, writing, listening and reading beside the socio-cultural implications underlying those structures. Today’s Algerian students of English may become teachers, clerks, participants in international meetings, tourists, or immigrants and they may need to communicate in English (or in the English they choose such as British or American or any other English 1). However, the act of oral communication will fail if speech is unintelligible or incomprehensible. It is crucial to use intelligible speech with a minimum of linguistic proficiency in a period when everything is assessed, analysed and studied.

The term ‘World Englishes’ according to Kachru (1986), encloses several types of English or Englishes (the inner circle, the outside and the extended one, and each refers to an English which is to some extent distinct from the other). If such a classification was conducted in the 1980s, now, four decades later, can we speak of the possible emergence of other Englishes such as ‘Algerian English’? Or, can we speak of an Algerian English pronunciation?

If we rely on the fact that the demand for English has soared in the Algerian labour market, and that the Algerian university students of English go through the same process of learning Arabic then French at school, it is possible then to suggest the following hypothesis. In the English pronunciation of Algerian students, we find recurrent and common phonetic/phonological aspects caused by Crosslinguistic Influence (CLI) from the previously acquired languages, and that makes it an Algerian English pronunciation.

This work deals with the CLI from Standard Arabic, Colloquial Arabic and French that could be depicted onto the English pronunciation of Algerian students at the Department of English at the University of Oran 2. A case study is conducted in order to verify the hypothesis, namely the existence of an Algerian English pronunciation. By the term ‘pronunciation’ in this paper, some phonetic/phonemic properties of the following are related: vowels, consonants and syllable structures. The main objectives of such a study are to analyse students’ pronunciation of English, to understand their difficulties and to identify whether English, spoken by Algerians, can be Algerian.

-

English Language Teaching

According to the statistics provided by the Ministry of Education, the academic year (2017-2018) admitted over 8 million pupils in primary, middle and secondary schools, a number that represents nearly 20% of the Algerian population2. Those pupils need to study twelve years throughout the three cycles of education to enter university. Before learning English in middle school, all of them learn a minimum of two languages (Standard Arabic first then French three years later) in primary school. English is taught as a Foreign Language for seven years out of those twelve (3h-4h/week), i.e. the duration of English learning ranges between 750 and 830 hours before university.

Proficiency in English entails a competence and performance not only in grammar and vocabulary but also in phonology and phonetics. Some English aspects of pronunciation such as stress or intonation need to be considered and followed in order to avoid unintelligibility or miscommunication. Nevertheless, on the one hand, some linguists such as Munro & Derwing claim that the chief goal of a learner is to understand and be understood in a variety of contexts. They claim that a foreign accent can sometimes impede this goal, but it can never be an overall barrier to communication: “Researchers and teachers alike were aware that an accent itself does not necessarily act as a communicative barrier” (Leather (ed.), 1999: 285). Additionally, in line with Heaton, we can communicate and be intelligible even if our English phonology and syntax are faulty: “People can make numerous errors in both phonology and syntax and yet succeed in expressing themselves fairly clearly.” (1988: 88).

On the other hand, consistent with the following statistics, pronunciation is considered as the most significant cause of unintelligibility. In 1974, Tiffen analysed what caused unintelligibility in Nigerian English. He found that syntactic as well as lexical mistakes represented only 8.8% of the reasons of intelligibility failure whereas pronunciation errors constituted as much as 91.2%, partitioned as follows: (a) Rhythmic and stress errors 38.2%; (b) Segmental errors 33%; (c) Phonotactic errors 20%. The effect of these statistics sustains the idea that there should be, to some extent, a homogeneity in pronunciation.

Indeed, when making Algerian students read a list of words and when there is no way to distinguish their meaning from the context, some pronunciation deviations may induce spelling ones; suffer and gone for example might be confused for sofa and gun. If pronunciation is to vary extensively and significantly in non-English speaking countries, it will probably cross the threshold level of unintelligibility. To a lesser extent, an altered pronunciation can modify, for instance, rhyming poems. However, the purpose is not to oblige Algerian students of English to speak and sound like the natives. The purpose is to guide Foreign Language learners through a process that enables them to produce intelligible discourse. A learner, who cannot realise speech sounds in the identically similar way a native does, should not be labelled as failing or unacceptable. Non-native speakers are not natives, and they need not be judged equally on all linguistic levels as such; learners should not feel trapped in inequality when learning: “…This is judging the students by what they are not—native speakers. L2 learning research considers that learners should be judged by the standards appropriate to them, not by those used for natives” (Cook, 1991 in James, 1998: 43).

Previously, English was composed of a collection of dialects used in particular by monolinguals within a limited shore. Now it consists of a wide range of non-standards and standards varieties, which are spoken at an international level, “English is now well on the way to becoming a world-language: and this means many types of English, many pronunciations and vocabulary-groups within the English language.” (Wrenn, 1949: 185).

Kachru (1986) divided English into three types called ‘English circles’. First, Inner Circle Englishes which includes older Englishes such as British, American, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, and South African Englishes. They are usually equated with native-speakers Englishes. Second, Outer Circle Englishes, it is where English has been introduced by a colonial system as in India, Ghana, Nigeria, Malaysia, Philippines, and Zambia. Third, Expanding Circle Englishes includes the English taught at school in countries having no colonial link with Britain, among those countries China, Japan, Russia, Brazil and so forth. In these countries, the norms are directly taken from Inner Circle Englishes. As to the norm the countries of Outer and Expanding Circles have selected remains problematic. India and Malaysia adopted British English whereas the Philippines American English because of different historical reasons. In addition to British and American Englishes being the norm, a third choice is put ahead, specifically Australian English, “Now the choice is getting wider, and South-East Asian countries are faced with an easily justified third choice—Australian English.” (James, 1998: 40).

According to some linguists, such as Kachru & Smith, the phrase ‘World Englishes’ “symbolizes the functional and formal variation in the language, and its international acculturation, for example, in the USA, the UK, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand” (1985: 210). Englishes have developed their own standard and codified varieties, even if the idea of standardisation contradicts that of ‘international language continuum’. Each English-speaking country has developed its own codified reference books (of English grammar, vocabulary, or pronunciation); however, the latter (reference books) are increasingly published to encompass more than one English variety:

– Daniel Jones Dictionary and Cambridge Advanced Learners’ Dictionary include British and American English.

– The New Oxford Dictionary of English includes English standards such as British, American, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, South African, and Indian.

– The Encarta World English Dictionary comprises British, American and Australian English.

– The Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English treats British and American grammars likewise.

– A Grammar of Contemporary English covers all English grammars.

However, English is not only spoken in the English-speaking countries, but many new Englishes have also emerged such as those produced in India, Nigeria or in the Philippines. The concern is very much the same but only bigger than it used to be. The more expansion English obtains, the more diverse it becomes and the more complicated its inventory will be. Besides, among the various and diverse definitions, what characterises English is that it is also spoken by non-native speakers for several reasons3. This seems to increase the complexity of developing a ‘super-standard’4, which can suit all factions.

There are several varieties, and what renders the situation more complicated is the fact that many non-native speakers use English. Such phenomenon hardens the identification of any particular variety as being the norm to teach. It is complex because several non-native speakers are increasingly using English as a means of communication. Indian English, for instance, which does not belong to the Inner Circle, is becoming an authentic norm for Indian teachers who are hired at schools (James, 1998: 40). Everybody has an accent when they speak their mother tongue or a foreign language, whether the accent is English RP or another. With such a situation and expansion of English, along with the importance of mutual intelligibility, on what foundation can we claim that an accent is better than another? Alternatively, for what reasons should a particular native accent be designated as superior to a non-native accent?

Students will become confused if their teachers use different pronouncing standards and request them to emulate their speaking choices. In Algeria, for instance, British English is taught at state as well as at private schools. In an interview with an inspector of west Algerian schools, Mustapha Louznaji states that the variety taught in Algeria is the British one. Even if there is no official decree enforcing that adherence to British English, it is implicitly suggested with the use and availability of British English reference and course books.

Speech sounds reflect society, and they are essential to carry the suitable meaning speakers try to convey. Besides, since sounds reveal a slight part of our identity, the English we use or ‘our English’ can sometimes bear the stamp of our culture and even that of our Algerian phonological system becoming, thus, to some extent ‘Algerian English’.

-

The Case Study: Investigating Algerian English Pronunciation

The subjects are 80 first-year students of English at the University of Oran II, 40 females and 40 males. All have studied and lived in Oran, Algeria. The experiment was to make them orally pronounce and phonemically transcribe 328 words. In English Phonetics classes, students need to produce and transcribe sounds and words in isolation and connected speech. The selection of those words was not based on what the informants had believed to have been difficult to assimilate but instead on what they had assumed to have been easily and well pronounced. In fact, the selected words were those the participants had believed to be non-problematic in class. The experiment lasted several weeks. Moreover, every time it was conducted, it was to respect a duration of one week or two following the instruction of a particular phonetic/phonological segment. For example, when the minimal pair /ɪ/, /iː/ was taught in class, for the experiment purposes, the subjects had to transcribe and pronounce words containing those sounds one or two weeks later.

After having recorded the informants’ pronunciation and collecting their transcription of the selected words, an analysis of the results was organised as follows. First, a comparison between the two types of collected data was made; second, sounds that were both pronounced and transcribed similarly were identified; third, common recurrent realisations were classified into categories; fourth, the major similar deviations in pronunciation and transcription were filtered according to their being the result of CLI from Standard Arabic, Colloquial Oranese Arabic and French.

The following examples enclose some frequent realisations observed in the transcription and speech of the informants. All the listed deviations are caused by a transfer of phonology from Arabic and French to English. The distinction between the front short and long vowel in ship/sheep is not noticed, so words having /ɪ/ or /iː/ are generally produced with [i]. The same realisation for both words is quite common since Arabic uses length mainly as a contrastive element in grammar. Central vowels seem to be the last to be acquired among all English vowels, and words having /ʌ/ such as money are either realised with [a] if the transfer is from Arabic or [o] if the transfer is from French. Other productions of central vowels might reveal to be front as in no /əʊ/ that is realised as [eːʊ] where the lips are slightly relaxed. Front vowels, however, such as /e/ or the diphthong /eə/ are produced as [ɛː] as in hair in which the front quality /e/ is articulated below and behind its presupposed position. Then, diphthongs such as /əʊ/ as in most /məʊst/ are, sometimes, changed into [ew] [mewst] where the second vowel becomes a consonant; becoming, thus, a rural Algerian diphthong.

As to consonants, although /θ/ and /ð/ exist in Standard Arabic and in some varieties of Colloquial Algerian Arabic, they do not exist in Colloquial Oranese Arabic; instead, they are replaced with [t] and [d]. The latter can be observed in the articulation of words such as athlete and brother. During the experiment, /θ/ – /ð/ are used when the reading is slow. However, when the participants were trying to read the words rapidly they tended to pronounce [t] and [d]. Furthermore, among other pronouncing deviations in English consonants, the following are found. /s/ when intervocalic as in disagree or disappear undergoes a French phonologic rule —when intervocalic [s] becomes [z]. These words are, therefore, realised as [dɪzəɡriː] and [dɪzəpɪə] instead of [dɪsəɡriː] and [dɪsəpɪə]. Next, unlike English, French initial or final voiced consonants, for instance, are fully voiced. In a word such as oui ‘yes’ /wi/, /w/ is fully voiced whereas /i/ is pronounced with a whisper phonation rather than a voiceless phonation. The English pronoun we /wiː/ is produced in the same way as the French oui /wi/ [ɥi̥].

The findings have revealed that the informants’ pronunciation of English sounds seems to be more influenced by French than by Arabic. Nonetheless, concerning syllable structures, the informants mostly apply Arabic syllable structures, as there is a tendency to insert a vowel between English initial consonant clusters. Arabic syllabic structure is usually CV or CVC as in kataba ‘to write’ or maal ‘money’, a word such as disappear /ˌdɪs.əˈpɪə/ which contains the following syllable structures cvc+v+cv becomes [ˌdɪ.zəˈpɪːr] with the following structure cv+cv+cvc.

The overall results prove that English vowels are the most difficult phonetic/phonemic segments to learn. Standard Arabic has 36 phonemes, among which eight are vowels. French has 37 sounds, among which 16 are vowels. Those numbers make Arabic and French a far less complicated vocalic system than that of English that has 20 vowels in addition to five other triphthongs. Students of English can utilise the target sound system with more or less important interference of their own phonological/phonetic properties. The native tongue or a recently acquired language influences foreign language performance because learning enfolds a new sound structure and new models of articulation and perception (James 1988) which only a few can master effortlessly.

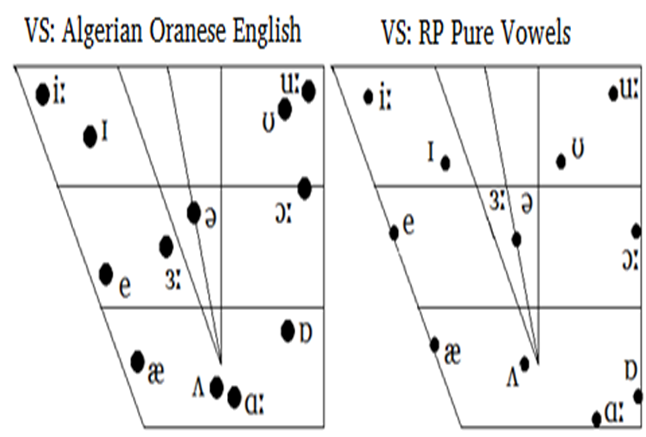

The following figure compares the places where RP English vowels are usually articulated and the places where first-year students of English tend to produce them.

Figure: Comparison between Colloquial Oranese English and RP Vowels

The left side of the figure represents the way the majority of those students would likely produce English vowels. The quality of the vowels, along with the consonants, undergoes CLI from French first, Standard Arabic second and Colloquial Algerian Arabic third. The reason why French heavily influences the Algerian pronunciation of English is primarily that of the Latin spelling. The English alphabet letters match the French ones; consequently, the informants generally realise them to correspond to the French phonology. English phonology can be challenging for foreigners to learn since there is no close relationship with English orthography.

Englishes are regularly referred to as, for example, American, Australian, or British English and so on. It does not necessarily mean that they are contrasting, but speakers of one country say, American speakers, for instance, have enough pronunciation features in common that are not perceptible in the speech of other people from other areas. Yet, American English is no more than a suitable label for a collection of local accents. No matter how small an area is, we can still find differences in pronunciation between the surrounding vicinities and between individuals themselves. Likewise, the several aspects that distinguish the Algerian pronunciation of English now might transform into an Algerian English variety later.

-

Conclusion

This work is open to future corrections since it is only at the level of hypothesis testing and it needs much more empirical research and constant improvement. Besides, it is quite difficult to extend the findings of a study conducted in Oran to all Algeria. In order to answer the research questions, the results of the experiment have demonstrated that there exists an Algerian English pronunciation. As to the existence of ‘Algerian English’, as a theoretical possibility, the question might be answered positively because of three major factors. First, the fact that the informants transfer from French first, from Standard Arabic second and Colloquial Algerian Arabic only third makes the features of French and Standard Arabic (two languages commonly learnt at school in Algeria) widely spread in the Algerian pronunciation of English. Second, even if the expression ‘Algerian English’ seems precipitate, it refers nevertheless, to a spoken form which is currently used and which may be analogous to any spoken dialect that has later become a written standard. Third, in a time of globalisation and social media and increasing demand for English, Algeria might soon find itself privileging English over French and use it as its first foreign language.

References:

GHLAMALLAH, N. R. (2007): Phonetics and Phonology of Standard Englishes in the British Isles, the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Unpublished Magister Thesis: University of Oran 2.

HEATON, J. B. (1988): Writing English Language Tests. London: Longman.

JAMES, A. R. (1988): The Acquisition of a Second Language Phonology: A Linguistic Theory of Developing Sound Structures. Germany: Gunter Narr Verlag Tübingen.

JAMES, C. (1998): Errors in Language Learning and Use: Exploring Error Analysis. London: Longman.

KACHRU, B. B. (1986): The Alchemy of English. Oxford: Pergamon.

KACHRU, B. B.; SMITH, L. E. (1988): “World Englishes: an Integrative and Cross-cultural Journal of WE-ness”, in E. Maxwell (ed.), Robert Maxwell and Pergamon Press: 40 Years’ Service to Science, Technology and Education. Oxford: Pergamon Press. 674-48.

LEATHER, J. (ed.) (1999): Phonological Issues in Language Learning. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers.

Mc ARTHUR, T. (2002): The Oxford Guide to World English. New York: Oxford University Press Inc.

TIFFEN, W. B. (1974): The Intelligibility of Nigerian English. Unpublished Dissertation: University of London.

WRENN, C. L. (1949): The English Language. London: Methuen.

1 In a previous study (Ghlamallah, 2007), we distributed a questionnaire to 268 undergraduates and graduates students having asked them which English accent they liked to learn. The majority of the students (64.93%) preferred RP English to other varieties. American English was second by 31.34%. Among all students, 1.86% liked both varieties, 0.75% favoured South African English and 1.12% had no preference at all.

2 The population of Algeria was estimated at 42.2 million in January 2018 by the National Office of Statistics www.ons.dz/

3 After learning English as a second language or as a foreign one, non-native English speakers might encounter situations in which they need to use the language for all sorts of reasons: academic achievement, tourism, business, science, technology, social media, fashion, etc.

4 Some linguists suggest a federation of standards so as to develop: “A ‘super-standard’ that is comfortable with both territorial and linguistic diversity.” (Mc Arthur, 2002: 448).