The communicability of interdisciplinary artistic research about global regions resistant to human habitation and tourism exemplified by a discursive exhibition at the Kunsthalle Wien in 2004

Lucas Gehrmann

Abstract

A presentation of an artistic, interdisciplinary field-trip through the northern Sahara, which was organized by the Institute of Art and Knowledge Transfer at the University of Applied Arts Vienna in 2003. As a result, the eight artists and six scientists developed projects that all share dealing with the confrontation of acquired images and ideas with actual local impressions and realities. These reflections were presented as a discursive exhibition at the Kunsthalle Wien and were also published in a comprehensive illustrated volume. Some of these contributions are featured in the presentation, as well as the discussion of how a predominantly artistic and experimental research project about a region, the peculiarities of which are being conveyed rather via myths and literatures than via the ‘exploration’ by mass tourism and media, can be translated into the format of an exhibition shown at other locations.

I am delighted to have the opportunity to talk about an exhibition with the title ‘Transfer Project Sahara’ I had the pleasure to curate at the Kunsthalle Wien in 2004, on the basis of an artistic-scientific expedition of the Institute of Art and Knowledge Transfer at the University of Applied Arts, and in cooperation with the university.

As part of the project ‘Digital World Museum of Mountains’, initiated by Herbert Arlt, this exhibition is still of interest today, not only because of its reference to the North African desert, its rock massifs and cultural property, but also in particular with regard to the problem of translating an interdisciplinary research projectrather an ‘exploration project’of this kind into the format of an exhibition. Therefore, first of all, I should like to say a few words about the history of the ‘Transfer Project Sahara’.

At the instigation of Prof. Christian Reder, head of the Institute of Art and Knowledge Transfer, eight artists accompanied him in October 2003 on a journey from Tripoli through the great desert for 21 days, and while doing so, they developed their own individual projects. A starting point was the aim to understand deserts and steppes – that constitute a third of the earth’s surface – less as fringe zones, but as a part of a globalized world, namely as historically as well as presently relevant transfer zones for humans, animals, cultural property and information between different cultures and geographical regions.

Another objective was to empirically sound out the gravity of preconceived ideas and images of the Sahara, meaning ideas and images brought along from Central European-Western cultural regions, through real events, situations and impressions on the ground.

In the more densely populated areas that are rich in vegetation and more frequented by tourists, the term ‘desert’ is commonly associated with ‘emptiness’, monotony and a hostility to life. According to this conceptjust as in today’s TV-reality only ‘barbarians’, who do not belong to any acknowledged ‘realm’, have lived there ….

Preconceptions of this kind do also exist on many other levels, and as a result, the ‘first world human’, who has been conditioned to be uncritical and trusting of mass media information, is not even tempted to question things, respectively to make certain efforts in order to verify them. Projects and exhibitions like the ‘Transfer Project Sahara’ or the ‘Digital World Museum of Mountains’ that is currently at a preparatory stage, are based on the experiences and the knowledge of those humans, who are open and curious and willing to make certain efforts to set out for those regions, and take apart from the vital necessities and knowledge ideally nothing with them that could burden them with any prejudice.

When they return to the so-called civilization they bring suggestions for dissolving the limitations of pre-programmed ideas: their own pictures, texts, notes, memories. Accordingly, Christian Reder said about the Sahara-Project: ‘If these suggestions are capable of disturbing unilateral concepts of North Africa and odd desert fixations, it will perhaps also become apparent, which opportunities for an integration-oriented ‘Mediterranean culture’ have already been ruined, and to what extent such potential could result in new perspectives at least in the long run.’

In order to work towards the desired objective, such ‘suggestions’ need to be ideally published and shown via various channels. Exhibitions constitute here one possibility. But if they are to travel to as many places as possible, their physical content cannot be too voluminous and too ‘valuable’ in terms of high-priced art. This means the costs for transport, insurance and implementation have to be kept down, and the whole exhibition package has to be flexible in order to be presented in an optimal way, regardless of the different spatial circumstances.

Illustration 1a: Kunsthalle Wien Karlsplatz, outside

For the exhibition ‘Transfer Project Sahara’ at Kunsthalle Wien, a space of 220 m² was available, three sides of which were confined by glass fronts and did therefore not offer much hanging space.

Illustration 1b: Kunsthalle Wien Karlsplatz, Sahara exhibition 2004, detail

But digital photographs and videos can easily be projected onto white panels of fabric hanging from the ceiling, or in front of the windows which can be slightly darkened. Elfie Semotan showed her desert photographs in cinemascope format with a length of 20 metres this way. And also, Michael Hoepfner brought back desert photographs that we displayed on the wall opposite, as large black and white printstoday even billboard size photographic prints can be produced inexpensively in every larger citytherefore they do not have to be shipped.

By contrasting these two photographs, two different perspectives on the desert landscape can be identified.

Illustration 2: Elfi Semotan, Licht, Horizont, Nähe, Nuancen (Sahara), 2003. Publ. in: Sahara. Text- und Bildessays, Vienna 2004, p. 48f.

Elfie Semotan always has an eye on the sky, for her, it constitutes an essential part of the scenario, as it is the source of the specific light above a desert. She states: ‘The Sahara is certainly the largest studio, the largest lightbox on the planet. The sun paints very crisp shadows with its harsh, directed light, that the bright desert reflects softly. This combination is beautiful. Every shape is captured by these lighting effects … Before modern lighting equipment existed, all films were shot in the desert, and often they still are. You do not easily get such lighting for a whole day somewhere else. It is calculable, there are no surprising changes … Here the light gushes down onto the landscape without any restriction (like architecture, vegetation), its simplicity makes us aware how full our realms of experience are.’

Illustrations 3a, b, c: Michael Hoepfner, circumambulations II, 2003. Publ. in: Sahara. Text- und Bildessays, 2004, pp. 228, 235, 125.

Michael Hoepfner says about his work: ‘Landscape photography is a very limited field. You have to plan very carefully what you are going to do. The common understanding is largely shaped by the style of Geo-Magazine or National Geographic, this pictorial beautification, harmonisation. Whereas art cannot be about documenting spaces, places and landscapes, but is about subjective, personal experiences and impressions. This cannot be separated from the deliberation of production methods: to walk, take one’s time, only take a few pictures! By intentionally using weak contrast, I reduce the space, change it into almost two-dimensional, grey scale areas. Only on closer inspection, an observer can realize how big all of this actually is in reality. The space has to be rethought … In my Sahara photographs, the horizon is left out. I aim at turning it into a general landscape, or just a desert, the localisation of which remains open. As soon as a human would appear in it, the picture could immediately be placed into known sequences. This is what I want to avoid. Although a geologist was recently able to tell me where they originated, as he classified the rock formations precisely. On this path, the deduction that leads back to the place becomes plausible again, because I do not use humans here.’

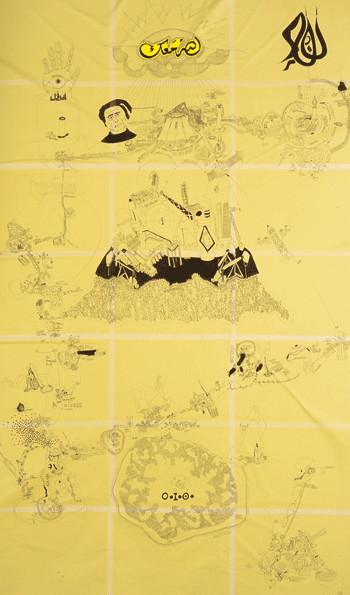

I should like to mention another artistic work, created during the 3-week-field-trip: media artist Grischinka Teufl was drawing every evening and produced in the end a map of 21 sheets, representing the memory of 21 days.

Illustration 4: Grischinka Teufl, mindscape, 2003. Publ. in: Sahara. Text- und Bildessays, 2004, p. 108f.

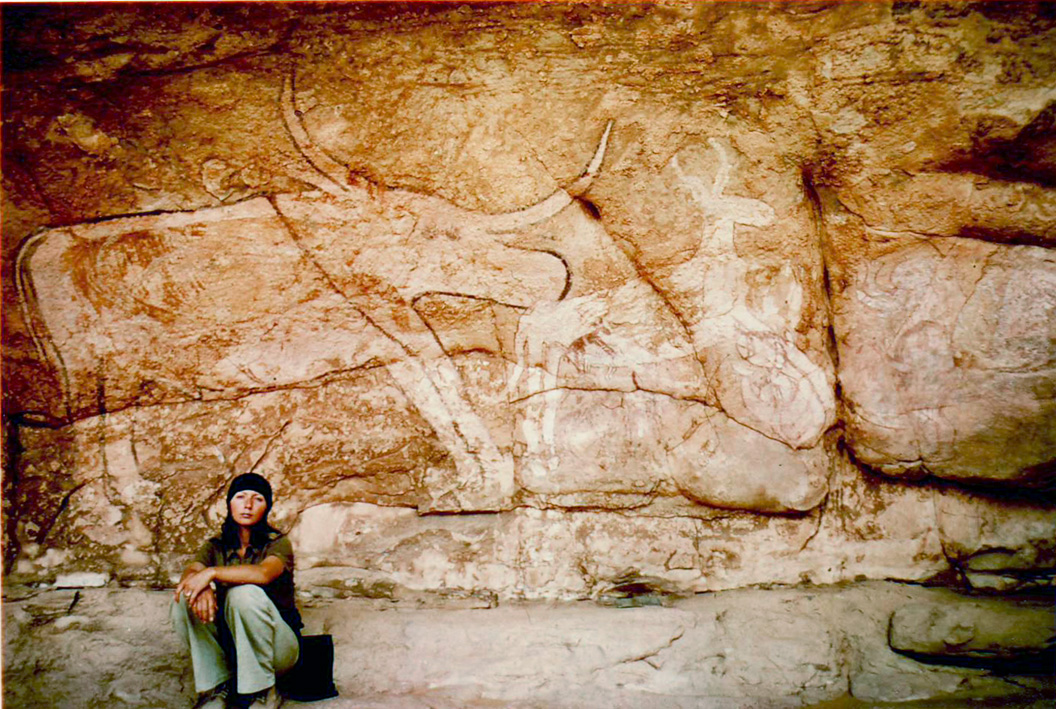

On this mindscape, or a ‘psychographic map’, you can see the addition of various cultural, civilizatory, religious and topographic drawings, including a small petroglyph that may indicate that Christian and Ingrid Reder have spoken about their trips to Tassili that evening, which they already undertook in 1973 and 1979.

Illustration 5: Christian Reder, Tassili-n-Ajjer, Algeria (with Ingrid Reder), 1973. Courtesy Christian and Ingrid Reder

Grischinka Teufl’s mindscape is, in any case, a very good suggestion to look at the Sahara in a multi-perspective mannerand this is certainly what these projects should be about: to depict various perspectives of a topic or object and to convey them via multimedia channels.

The publication that accompanied the exhibition and is out of print by now, comprised numerous essays, interviews, and a ‘Sahara-encyclopaedia’ containing depictions of historically, literary, cinematic and other relevant historico-cultural aspects. The project therefore not only amounted to offering ‘information’ but also to the illustration of personal experiences, reflections and associations.

And when Herbert Arlt finds new ways for representation in his project ‘Digital World Museum of Mountains’, for which the traditional exhibition format as well as the catalogue will only be playing a minor role, the ‘Transfer Project Sahara’ can still be regarded as an example for the recording and combination of those materials, which later will be travelling across the globe via extended quantum computer technology.

But even such multimedia communication cannot replace what Rainer Metzger wrote in his contribution to the publication: ‘What one can experience within a space, are the specific cases, at which a lingering or a passage occurs. It is the situation.’

Illustration 6: Ivo Kocherscheid, Kamele, Libyen 2003. Press photo Kunsthalle Wien

However, it will hopefully be an inspiration to leave the weatherproof privacy of one’s home and the (digital) libraries and climb into the next available Land Rover or even onto the saddle of a dromedary.

Literature:

Sahara. Text- und Bildessays. Ed.: Christian Reder, Elfie Semotan. Edition Transfer at Springer Wien—New York, 2004. Excerpts (in German) see: www.christianreder.net/archiv/b_04_sahara_inh.html, and www.christianreder.net/archiv/p_04_10_13_stand.html

Translated from German into English by Susanna Fahle.