Amira Benader

LMDSTEAD Research Laboratory,

Doctorante à l’Université d’Oran 2

Abdelkader Lotfi Benhattab

LMDSTEAD Research Laboratory

Université d’Oran 2

Abstract:Almost all languages contain words and expressions that are daily used and considered as polite. With the emergence of Brown & Levinson’s (1987) Theory of politeness, this phenomenon became a subject of interest to researchers in pragmatics, sociolinguistics, social psychology and anthropology. This study explores politeness as an important aspect in social interactions, reviewing the most prominent theories that have attempted to account for this concept. We have conducted this study as an attempt to adapt Brown & Levinson’s model of politeness to a selected number of speakers of the Algerian dialect of Annaba. This case study addresses three fundamental questions related to the usage of politeness strategies in social communications, the existence as well as the conceptualisation and the perception of the notion of face by the selected speakers of the Algerian dialect of Annaba and its applicability to the sample population of this case study. The data of the study were retrieved through a conversation recording that was analysed following a mixed methods approach to research. The findings of this case study revealed how the participants use positive politeness, negative politeness and off record strategies to show politeness. This work also proved that the selected speakers of the Algerian dialect of Annaba rely on their own intentions as a partial measurement of face threat. We have concluded that Brown & Levinson’s model of politeness can be partially adapted to our sample.

Key words: Algerian dialect – Brown & Levinson’s model – face-threatening acts -politeness – politeness strategies

الملخص:

تحتوي كل اللغات غالبا على كلمات وعبارات تستخدم يوميا، و تضم إلى مجموع العبارات المهذبة. لكن مع ظهور „نظرية التهذيب“ لبراون وليفنسون (1987)، أصبحت هذه الظاهرة مركز اهتمام باحثي علم البراغماتية، علما لاجتماع اللغوي، علم النفس الاجتماعي، والعلوم الإنسانية. تظهرهذه الدراسة التهذيب كزاوية مهمة من التفاعل الاجتماعي، و تُراجع مبدئيا أكثرالنظريات البارزة التي حاولت التعرض لدراسة „نظرية التهذيب„. لقد قمنا في هذه الدراسة بمحاذات نموذج نظرية براون وليفنسون للتهذيب، وذلك على عينة من الناطقين باللهجة الجزائرية لعنابة. تطرح هذه الحالة الدراسية ثلاثة أسئلة أساسية مرتبطة باستعمال الاستراتيجيات المهذبة في التواصل الاجتماعي؛ تواجد، تصور،وإسقاط مفهوم „الوجه“ من قبل الناطقين باللهجة الجزائرية، بالإضافة إلى قابلية تطبيق هذا النموذج على العينة الاجتماعية لهذه الحالة.جُمعت بيانات هذه الدراسة من خلال تسجيل حواري، قمنا فيما بعد بتحليلهم متبعين في ذلك طريقة مقاربة المنهجيات المختلطة. أثبت العمل أن العينة المدروسة يعتمدون على مقاصدهم كمقياس جزئي للحفاظ على „وجه“ الآخربعدم الاعتداء، ومنه استنتجنا في نهاية الدراسة إمكانية تطبيق نموذج „نظرية التهذيب“ جزئيا على العينة المدروسة.

الكلمات المفتاحية: الأفعال المهددة للوجه، استراتيجيات التهذب، التهذب، اللهجةالجزائرية، نموذج براون وليفينسون

-

Introduction

Politeness is a fundamental concept in social communications in everyday interactions in all societies. However, this phenomenon is conceptualised, manifested and perceived differently across cultures and among individuals, depending on a set of various interrelated cultural and sociological variables. However, since the establishment of Brown & Levinson’s (1987) model which is considered the most prominent pragmatic account of politeness, the phenomenon subsequently became the subject of interest to several scholars in the field of pragmatics and sociolinguistics. The key concept of Brown & Levinson’s (1987) model is face to which they claim universality. Researchers, namely Mao (1994), Nwoye (1992), Gu (1990), Ide (1989) have observed this notion in Asian languages such as Chinese and Japanese. Their studies partially or totally rejected the universality if this notion.

The aim of this work is to examine the politeness phenomenon in the Algerian society and questions the strategies through which the selected speakers of Algerian dialect of Annaba manifest politeness. No such investigation has been conducted on speakers of the Algerian dialect of Annaba. It particularly investigates the existence of the notion of face, face-threatening acts and face-saving strategies and assesses the applicability of Brown & Levinson’s (1987) model as well its applicability to natural occurring conversations in the Algerian dialect of Annaba.

-

Brown & Levinson’sTheory of Politeness

Brown &Levinson’s model was first introduced in Questions and Politeness: Strategies in Social Interactions (Goody, 1978). This model was further developed and republished in Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage (1987). Politeness theory introduces some notions that are considered to be universal such as the notions of face and face-threatening acts.

-

- The Face-Saving View

Up to present time, the face-saving view is the most significant and systematic account of the concept of politeness. It is essentially based on Brown &Levinson’s (1978, 1987) theory of politeness which revolves around rationality, Grice’s (1975) CP (Cooperative Principles) and the notion of face.

Brown & Levinson (1987) define rationality as a “precisely definable mode of reasoning from ends to the means that will achieve those ends” (p. 63). The notion of face was first suggested by Goffman (1967). According to Brown and Levinson, it is “the public self-image that every member [of society] wants to claim for himself” (p. 61). Following Grice’s CP, and according to the notions of face and rationality, a conversation is spontaneously distinguished by the absence of “deviation from rational efficiency without a reason”. Brown & Levinson (1987, p. 5)

-

- The Notion of Face

Contrary to previously cited researchers, namely Lakoff (1973) and Leech (1983), Brown & Levinson account for the concept of politeness in contrast to impoliteness. They define politeness mainly in terms of FTA i.e. impoliteness.

Brown & Levinson’s (1987) model of politeness revolves around the notion of face which will be the subject of our research. Their notion of face is originally based on a concept initially suggested by Goffman (1967) who combines face to people’s everyday interactions. He argues that every individual is concerned, to varying degrees, with how other people regard them. Additionally, Brown & Levinson rely on the English folk word face which denotes the act of being “embarrassed” or “humiliated” or “losing face”. Unlike anthropologists, Brown & Levinson consider face’s features as “basic wants” instead of social “norms” or “values” (1987, p 62). They further argue that face is “emotionally invested, and that can be lost, maintained, or enhanced, and must be constantly attended to in interaction” Brown & Levinson (p. 61). Thus, individuals within a conversation assume reciprocal preservation of each other’s face. When face threatening occurs, the participants naturally defend their face. To avoid such situations, it is recommended that participants preserve each other’s face.

-

-

The Universality of Face

-

Brown & Levinson (1987), as well as Goffman (1975) claim the universality of face with regard to what this notion might signify in each speech community taking into account the cultural differences. The particular focus attributed to face is due to the fundamental and universal nature of this notion.

Brown &Levinson’s claim of the universality of face has been welcomed by varying criticism perspectives; some researchers totally rejected the universality claim of Brown & Levinson while other researchers, mainly Mao (1994), adopted a neutral standpoint. In their politeness model, Brown & Levinson support their claim by providing supporting examples and evidence from three dissimilar languages i.e. English, Tzeltal and Tamil. Scholars who contested Brown & Levinson model worked mainly with non-Western languages, particularly Chinese and Japanese. In investigating the universality of face, researchers, namely Mao (1994), Nwoye (1992), Gu (1990), Ide (1989) analysed this notion in Asian societies and provided examples from Asian languages in contrast to Western languages. In his critical examination of Brown & Levinson theory of politeness, Matsumoto (1989) asserts that negative face and the need of maintaining one’s personal territory does not typically distinguish the Japanese culture. Instead, the presence of honorifics within social interactions is indispensable regardless of FTAs occurrence. Ide (1989) examined the concepts of Brown & Levinson framework from a “non-western perspective” (p. 240). She argues that face does not account for honorifics as well as the notion of group membership. She highlights that Brown & Levinson’s model puts emphasis on volitional politeness i.e. the speaker can decide to be polite or not regardless of the social context, while it neglects discernment politeness i.e. the speaker chooses strategies of interaction depending on the social context. Watts (2003). Volitional politeness and discernment politeness corresponds to Kasper’s (1990) “strategic politeness” and “social indexing” respectively. Ide further argues:

“For the speaker of an honorific language, linguistic politeness is above all a matter of showing discernment in choosing specific linguistic forms, while the speaker of a non-honorific language, it is mainly a matter of the volitional use of verbal strategies to maintain the faces of participants.” (Ide, 1989: 245).

According to Gu’s (1985, 1990) self-denigration maxim, Chinese people tend to “(a) denigrate self and (b) elevate other” (1990, p. 246). Contrary to what Brown &Levinson’s model suggests, Chinese politeness is normative and not instrumental. Consequently, Gu concludes that Brown and Levinson’s model “ha[s] failed to go beyond the instrumental to the normative function of politeness in interaction.”(1990, p. 242).

Mao (1994), as previously mentioned, does not renounce Brown & Levinson’s notion of face. He examines the Chinese conceptualisations that correspond to the notion of face in Brown & Levinson’s model, i.e. Mientzuand lien, suggested by Hu (1944) and Ho (1976). Mientzuis a “kind of prestige” and “a reputation achieved through getting on in life through success and ostentation”. Hu (1944, p. 45). As for lien, it stands for “the confidence of society in the integrity of ego’s moral character, the loss of which makes it impossible for him to function properly within the community”. Hu (1944, p. 45).

De Kadt (1998), Mao (1994), Ting-Toomey (1988) and Scollon&Scollon (1995) acknowledge that the conceptualisation of face in Western cultures contrasted with Asian cultures originates from the diverse perceptions of the concept of self. Ting-Toomey argues that the projection and maintenance of an authentic self and social self among individuals “varies in accordance to the cultural orientations toward the conceptualizations of selfhood.” (1988, p. 215).

Ting-Toomey &Cocroft put an emphasis on the significance of individualism and collectivism in cross-cultural communication. Individualistic societies associate self to “personal achievements and the self-actualization process” while collectivistic societies relate self to “ascribed status, role relationships, family reputation, and/or workgroup reputation.”(1994, p. 314). Thus, the perception of the notion of face in individualistic and collectivistic societies varies accordingly. In individualistic societies, face “is associated mostly with self-worth, self-presentation, and self-value, whereas in collectivistic cultures face is concerned more about what others think of one’s worth” Lin ( 2005, p. 44).

-

Adapting Brown & Levinson’s Theory to Algerian Speakers

Considering the research questions and taking into account the nature of politeness as a phenomenon, we can assume that the case study approach and a qualitative research design are most suitable to be adapted to our study.

-

-

Population

-

The population involved in the study consisted of two groups of a male and a female adult in their mid-twenties who were chosen randomly. Participants of both groups were native speakers of the Algerian dialect of Annaba. By the time of the recording, participants were graduate students at BadjiMokhtar University. The participants of both groups are completely unknown to each other.

-

-

Site

-

The study was conducted in D.Bros, a restaurant situated in Annaba, north East Algeria. This place was chosen because the conversation needed to take place in a natural and an informal setting.

-

-

Instrumentation

-

The tools used to collect the data consisted of small audio recorders that were placed by a participant of each group in the absence of the researcher. The audio recorders captured a three hours long recording for the two groups.

-

-

Data Collection

-

The participants of each group were informed beforehand about their tasks during the procedure and were asked to have a natural and a casual face-to-face conversation. However, the four participants were deliberately not informed about the purpose of the study, which is the examination of politeness, in order to ensure the validity of the data retrieved.

The data which were retrieved through the previously described procedure were not fully used. An excerpt of one hour that has been recorded by only one group was used in the case study.

-

-

Data Analysis

-

In the present study, the analysis of data occurs in a sentence-level. A deductive approach is adopted when analysing the chosen segment since the analysis is based on a pre-existing theory. Data of the segment are classified into two main categories which are face-threatening acts and politeness strategies. Thus, the units of analysis are mainly politeness strategies used by the participants and the face-threatening acts they perform in the segment. Politeness strategies categorisation includes positive politeness, negative politeness, bald-on record, and Off-record strategies while face-threatening acts categorisation includes positive face-threatening acts and negative face-threatening acts. The impact of face-threatening acts on both the hearer and the speaker, as outlined in Brown & Levinson’s (1987) model, will be identified.

-

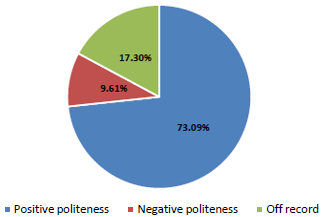

How Participants Manifest Politeness

Participants in this study showed politeness by realising positive politeness, negative politeness as well as off-record politeness strategies.However, we have noticed a total absence of on-record politeness strategy. The results are illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 3. The Use of Politeness Strategies by the Selected Speakers of the Algerian Dialect of Annaba.

-

-

Positive Politeness

-

According to the general context of the conversation, the participants‟ use of positive politeness at the beginning of the segment did not aim at redressing any positive or negative face. Since participants were completely unknown to each other, the main aim of the sub-strategies used such as noticing, attending, exaggerating and intensifying interest to both the speaker and the hearer and telling or asking the reason was to generate a conversation. As the conversation goes on, the social distance decreases; we notice that the two participants make use of jokes.

We can thus assume that the social distance has an important impact on the use of these positive politeness sub-strategies.

Sub-strategies such as seeking agreement and showing common ground, understanding, and cooperation were used by both participants within the flow of the conversation. In the case of showing common ground, we have noticed a high frequency of continuers that were not necessarily words or sentences but merely sounds such as “mmh”, “heh”. Such continuers were mainly used to achieve cooperation which ensures the smooth conversational flow.

Additionally, participants used another strategy that was, surprisingly, not outlined in Brown &Levinson’s (1987) model. In the following example, the speaker L discusses an issue related to his field of studies. The hearer S implicitly shows that she is listening carefully to L and conveys this idea as she anticipates a word that L is about to say and say it before L says it.

(27) L : [Ça fatigue], ᶜandnanafs el-muškel f-el-[/physique/] f-el-[physique]hādi-hi [la spécialité] li kuntḥābhabaᶜd

“It’s tiring we have the same problem in /physics/ in physics this is the very specialty that I wanted‟

In some other contexts, such strategy might be considered as an impolite interruption and can be classified under the category of face-threatening acts that damage the hearer’s positive face. We assume that what defines the nature of such strategy is the age difference between the speaker and the hearer. In other words, this strategy is considered polite when the speaker and the hearer in a given conversation are about the same age while it might be interpreted as an impolite strategy if the age difference between the speaker and the hearer is significant.

Participants‟ use of jokes as a positive politeness sub-strategy depends on the context and the topic of the conversation. When participants discussed academic issues, fewer jokes were noticed during the analysis. However, when speaking about their personal interests and hobbies, the participants‟ use of jokes increased.

Additionally, we have noticed the use of religious expressions such as “ᵓallāhybārek” “God bless (it)”, and “Y’barekfik” „And Bless you‟. The use of such expressions is influenced by the Islamic culture in Algeria which we perceive as another variable that interferes with the speaker’s choice of politeness strategies.

-

-

Negative Politeness

-

During the conversation, we have noticed a limited occurrence of negative politeness strategies. Negative politeness strategies mainly aim to avoid any potential imposition that the speaker might perform on the hearer. Consequently, the use of such strategies intends to preserve the speaker’s autonomy vis-à-vis the hearer and maintain a social distance. We have already highlighted the implicit attempt of the participants to reduce the social distance. We can conclude that the uncommon use of negative politeness strategies is due to the mutual desire to reduce social distance between the participants.

-

-

How Participants Maintain Face

-

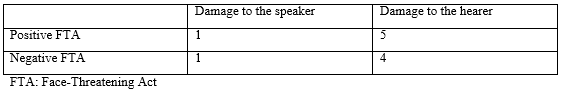

As previously explained, participants did not consciously use face-threatening acts. Table 1 illustrates the results obtained:

Table 1. FTAs frequency in the conversation of the selected speakers of the Algerian dialect ofAnnaba

However, some FTAs that damage, according to Brown & Levinson’s (1987) model, both the speaker’s and the hearer’s positive and negative face were identified. In view of the surrounding contexts of these FTAs, participants did not even consider these acts as face-threatening. We conclude that what matters the most is the speaker’s intentions which the hearer is supposed to obviously understand. However, such conclusion cannot be generalised as this aspect depends on the weight of the FTA

-

New Classification of FTAs

We can therefore establish a new classification of face threatening acts regardless of the type of face threatened as follows:

-

-

Intentional FTAs

-

The speaker is conscious about the threat of the act he performed and uses a self-justification strategy to redress the hearer’s face. The self-justification might occur before or after the FTA, hereby referred to as pre-FTA self-justification and Post-FTA self-justification.

-

-

-

Pre-FTA Rectification

-

-

When the speaker measures the risk of the conscious FTA before its occurrence, he/she has a tendency to rectify and redress the meaning he/she intends to convey before performing it. The following examples demonstrate this aspect:

(28) S: euh ..[mais] āna ..[jeparle de moi-même] ..m-el [le genre] li-enmīlšwi [li-el-[coté]Kabyle

-

-

-

Post-FTA Rectification

-

-

When the speaker performs an FTA, he/she expects the understanding of the hearer. The speaker then assesses the risk of the threat following the hearer’s reaction. In cases of suspicion, the speaker uses the post-FTA rectification strategy to ensure that the right meaning has been conveys properly. The following example illustrates this aspect:

(29) S: euh ..[mais] āna ..[jeparle de moi-même] ..m-el [le genre] li enmīlšwi [li-el-[coté] Kabyle

Euh ..but I am talking about myself .. I have a preference for Kabyle

L : Ah [oui] ?

S : mm .. [non]meš[par racism] wella

‘mm ..not being a racist or something’

(30) S :mh..[vraiment] sāmaḥnibaṣṣahel-ḥaḍāramešgāysethum

‘mh .. excuse me really but they are not civilised‟

L: saḥ

‘Oh yeah?‟

S :[je sais pas] āna .. elᶜbādel-līruḥt-elhum

‘ Idon‟t know .. people I visited’

We conclude that the speaker and the hearer show mutual concern for each other during the conversation which proves the existence of the notion of positive face. However, this notion is perceived and conceptualised differently compared to Brown &Levinson’s model.

-

-

Unintentional FTAs

-

Participants in this study used some FTAs and they assumed, according to the context of their occurrence, that these FTAs do not constitute a threat to the hearer’s face or to their own face. Consequently, they do not attempt to rectify such FTAs.

-

Conclusion

The present study investigated the use of politeness strategies by a number of selected speakers of Algerian dialect of Annaba. We have discussed the findings of this study with regard to Brown &Levinson’s (1987) model of politeness. The results of our study lead us to the establishment of a new classification of FTAs through which we have introduced two aspects that we referred to as pre-FTA rectification and post-FTA rectification. Due to the flexibility of the phenomenon studied, we cannot assume the generalisation of any of the results obtained.

References

Brown, P. & Levinson, S. (1987). Politeness: Some Universals in Language Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

De Kadt, E. (1998). The Concept of Face and its Applicability to the Zulu Language. Journal of Pragmatics, 29(2), pp.173-191. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378216697000210

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face to Face Behavior. Garden City, New York. Retrieved from http://libgen.io/ads.php?md5=E595DDA768939373807C5DBFD95BF3BC

Goody, E. (1978). Questions and Politeness: Strategies in social Interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from https://books.google.dz/books?id=qDhd138pPBAC&redir_esc=y

Gu, Y. (1990). Politeness Phenomena in Modern Chinese. Journal of Pragmatics, 14(2), pp. 237-257. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/037821669090082O

Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and Conversation. In P. Cole, & J. L. Morgan. (Eds.), Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3, Speech Acts (pp. 41-58). New York: AcademicPress.

Hu, H. (1944). The Chinese Concepts of „Face“. American Anthropologist, 46(1), pp. 45-64. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1525/aa.1944.46.1.02a00040/epdf

Ide, S. (1989). Formal Forms and Discernment: Two Neglected Aspects of Universals of Linguistic Politeness. Multilingua – Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication, 8(2-3), pp. 223-248. Retrieved from http://www.sachikoide.com/1989b_Formal_Forms_and_Discernment.pdf

Kasper, G. (1990). Linguistic Politeness: Cuurent Research Issues. Journal of Pragmatics, 14(2), pp. 193-218. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/037821669090080W

Lakoff, R. (1973). The Logic of Politeness; or Minding Your P’s and Q’s. Papers from the 9th Regional Meeting, Chicago Linguistic Society, 9, pp. 292-305. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240319202_The_logic_of_politeness_or_minding_your_p“s_and_q“s

Leech, G. (1983). Principles of Pragmatics. Essex: Longman. Retrieved from http://libgen.io/ads.php?md5=C0920B9EBFAE1EAFC8320064014326DD

Lin, H. H. (2005). Contextualizing Linguistic Politeness in Chinese -A Socio PragmaticApproach with Examples From Persuasive Sales Talk in Taiwan Mandari(Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved fromhttps://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file%3Faccession%3Dosu1109961198%26disposition%3Dinline

Mao, L. (1994). Beyond Politeness Theory: ‘Face’ Revisited and Renewed. Journal ofPragmatics, 21(5), pp. 451-486.Retrieved fromhttp://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0378216694900256

Matsumoto, Y. (1989). Politeness and Conversational Universals Observations FromJapanese. Multilingua – Journal of Cross-Cultural and InterlanguageCommunication, 8(2-3), pp.207-222. doi: 10.1515/mult.1989.8.2-3.207

Nwoye, O. (1992). Linguistic Politeness and Socio-Cultural Variations of the Notion of Face.Journal of Pragmatics, 18(4), pp. 309-328.Retrieved fromwww.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/037821669290092P

Scollon, R. and Scollon, S. W. (1995). Intercultural Communication: A Discourse Approach.Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Retrieved fromhttps://books.google.dz/books?id=HyAbmSqOPsoC&redir_esc=y

Ting-Toomey, S. (1988). Intercultural Conflict Styles: A Face Negotiation Theory. In Y. Y.Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.). Theories in Intercultural Communication, pp.213–238. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Retrieved fromhttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/246501516_Intercultural_conflict_styles_A_face-negotiation_theory

Ting-Toomey, S., &Cocroft, B. A. (1994). Face and Facework: Theoretical and ResearchIssues. In S. Ting-Toomey (Ed.), The Challenge of Facework: Cross-Cultural andInterpersonal Issues pp. 307–340. Albany: State University of New York Press.Retrieved from https://books.google.fr/books?isbn=079141633X

Watts, R. (2003). Politeness. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved fromhttps://books.google.fr/books?isbn=0521794064