Nahed Rajaa GHLAMALLAH

University of Oran 2

Abstract: This paper tries to answer the question related to whether we need to choose or not one English Standard in our classes at schools and universities. Since English has arisen as a world language, it is incumbent upon academic staff to determine the most useful Standard to Algerian learners of English. The selection of a particular English does not necessarily stem from its being a world language but sometimes from its being a commodity that serves speakers’ purposes and interests. Choosing a Standard English as a commodity language in the market of languages might prove more complex than the adoption of a lingua franca. The present study aims at providing some answers from university students’ perspectives and some of the learning constraints the English language teaching entails in Algeria.

Keywords: Algeria, EFL, Language Acquisition, Learning, Teaching, Standard English

Introduction

English will keep on culturally and phonetically discriminating many speakers all over the world. English is increasingly used as a world language, a sociolinguistic phenomenon that makes us wonder whether English characterises the British people and their descents or, simply, all those who use it. And if so, what standard English can be most practical in Algeria and which ‘Standard English’ is to be taught at schools and universities.

As a teacher of English phonetics, several questions need to be addressed: how can the assessment of students’ progress in pronunciation be affected if each student picks up the English pronunciation of their liking? After all, it is still Standard English. Can we oblige or expect a similar pronunciation from all students? Which English and whose norm do we, Algerians, should preferably learn or teach in our classes? As Africans, should we not promote the teaching of Standard South African English? Which of the following criteria is relevant to determine the English taught in Algerian institutions?

-

Economic and Political agreement between countries

-

Educational, scientific and technological criteria

-

Socio-cultural aspects and social media tendencies

-

The availability of the documentation in our local libraries.

Undoubtedly, the choice would be limited to no more than three varieties of English such as British, American, and probably South African English. However, can a combination between them be the key to solve the problem or should each teacher or learner decide on the variety to use? We can assume that such a combination might add to the complexity of the teaching/learning process.

Students already have difficulties in learning one foreign language, and annexing more standard varieties may augment their difficulty in acquiring English. Students may not stick to one English during an examination in Phonetics or Phonology and which in itself disturbs evaluation. How can a teacher grade a student’s work and discern between what is ‘wrong’ from what is ‘correct’? How can students be satisfied with their results? How can we know that the students do really know the difference and that they do not answer radomly? Indeed, the selection of a standard seems to be a hard task ––what standard(s) to choose, when it/they is/are taught, and how much of it/them should be exposed to learners remain fundamental.

Assessment, formative or summative, seems to be up to now the most representative method to reflect students’ achievements, learning, and attitudes towards knowledge. The teacher has to evaluate mistakes and errors according to their importance or to the learning priorities and objectives. It must not be seen as a devaluation of the learner but rather an insight into students’ linguistic deviations. The teacher has to provide reasons for any given value/mark instead of another. Besides, evaluation is also a sociocultural factor “Evaluation is indeed a matter of ethics, since society rewards those who get things right—what counts as right being decided upon consensually by each society, or at least by those who wield power in that society.” (James, 1998: 205). Assessment may become an ideology, which is the vehicle of culture and socialisation rules of the community.

-

World Language vs Commodity Language

Nowadays, the world does no longer seem to be an immense planet; the earth has become one single area and its inhabitants its dispersed neighbours. English is mostly used as a medium of instruction and it is the most prominent language in which many articles and books are published. The reason for English popularity does not merely rely on its having a simplified grammar, spelling, or pronunciation. In fact, Chinese grammar, Arabic spelling, or Spanish pronunciation are less complicated than those of English. The latter is a world language, and many linguists such as Quirk (1981) consider it as the best means to enhance and reinforce international communication; for no artificial language could rival or fulfil such a function. People from different speech communities may communicate in English in meetings, trips or social media platforms. And it does not really matter whether the pronunciation they use entirely obeys the phonological rules of the ‘target’ language provided that they can communicate with one another.

On the one hand, English has become a world language, and it might be taught as such. A world language can consist of a combination of British and American English. Nevertheless, what remains more problematic in teaching English as a world language is to determine how we can estimate or determine the share of each variety. On the other hand, choosing a Standard English over another can also be regarded as a commodity. Deborah Cameron, in her article about English as a commodity language in the market value of languages, states that acquiring or maintaining a language depends on what languages stand for. Language has some economic value in the market of languages because of its symbols of identity or some “prestigious vehicles of ‘high culture’” and learners may favour forms of linguistic capital (Cameron, 2012: 354). This statement allows us to consider that learners may favour a language over another because of what it represents. Language attitudes are a consequence of cognitive development during the perception or the production of the target language, and that might elicit language attitudes or beliefs of what some languages reflect.

-

Whose English?

From a sociolinguistic standpoint, the question of which and whose language should be taught raises a very complex issue: what norm? Whose norm? Whose English? An English speaking country may promote its variety domestically, but what grants it the right to choose which English, others, must learn? How about South African English, which is also a native speaker variety? How about Scottish English that has a ‘nice’1 sound? Several debates on the teaching of English have drawn particular attention to the challenging question of which Standard English should be taught. According to Wilkinson: “There is, however, a bigger problem with the teaching of Standard Spoken English—the imposition of a ‚capital‘ language on a ‚mountain‘ language.” (Carter (ed.), 1995: 43).

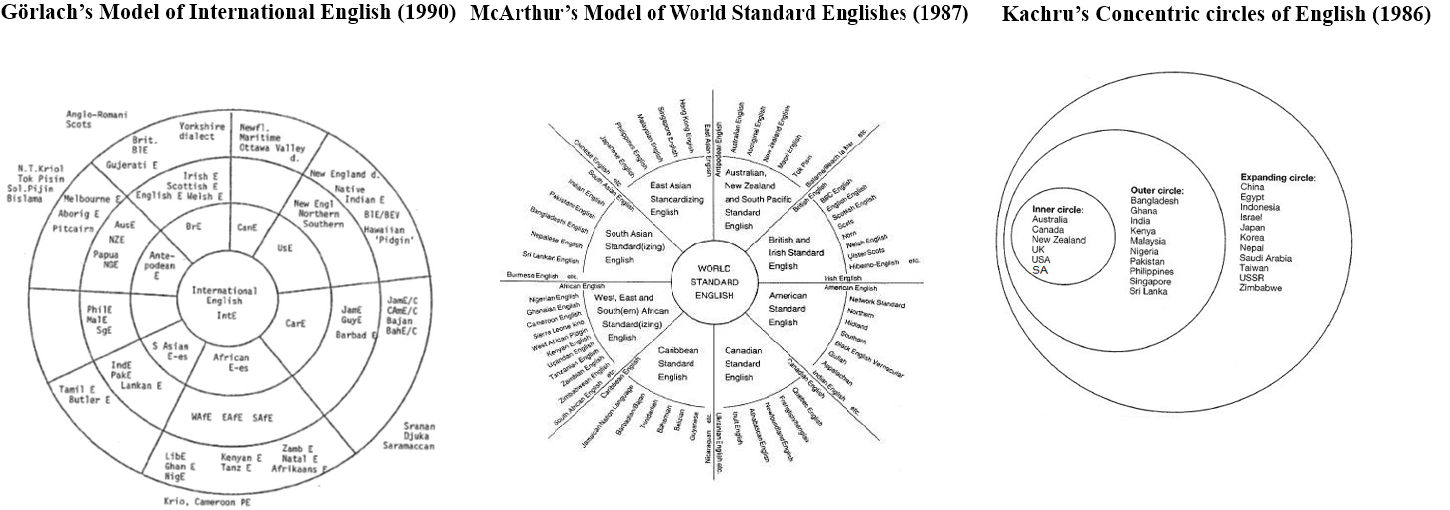

Several scholars, who worked on the matter, have described and categorised Standard Englishes, and among those, we find the following diagrams:

Kachru (1986), for instance, divides English into three types labelled ‘English circles’:

– Inner Circle (Englishes): it includes older Englishes such as British, American, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand, and South African Englishes. They are typically equated with native-speakers Englishes.

– Outer Circle (Englishes): it includes the countries where English has been introduced by colonialism such as India, Malaysia, Nigeria, Ghana, Zambia, or the Philippines.

– Expanding Circle (Englishes): it includes English taught at school in countries having no colonial link with Britain, among these countries China, Japan, Russia, Brazil, and so on. In those countries, the codification norms derive from Inner Circle Englishes.

As to the norm, the countries of Outer and Expanding Circles might select, remains problematical; Malaysia and India adopted British English whereas the Philippines American English. Besides, a third choice is put ahead—Australian English (James, 1998: 40). There are several English varieties, and what renders the situation more complex is the fact that many non-native speakers are increasingly using English as a means for communication and financial transactions. Such a phenomenon toughens the identification of any specific variety as being the standard to teach. Indian English, for instance, a variety, which does not belong to the Inner Circle Englishes, has developed into an authentic norm for Indian teachers who are employed at schools (James, 1998: 40). Whether one speaks their mother tongue or a foreign language such as English RP, everyone has an accent. On what basis, therefore, can one allege that an accent is better than another or even that a native accent is more befitting than a non-native one?

The importance should mostly depend on mutual intelligibility and comprehensibility in a variety of contexts. On the one hand, according to Leather, a foreign accent, even a strong one, may not hinder intelligibility (1999: 9). On the other hand, Griffen equates foreign accent to language pathology; he believes that a foreign accent is a bad thing and must be subject to treatment, intervention, or even eradication (1991: 182). However, consistent with the following statistics, pronunciation is considered as the most critical cause of unintelligibility. Tiffen (1974: 227) analysed what causes unintelligibility in Nigerian English. His findings reveal that syntactic, in addition to lexical mistakes, represent only 8.8% of the reasons of intelligibility failure whereas pronunciation errors constitute as much as 91.2%, partitioned as follows: (1) Rhythmic and stress errors 38.2%, (2) Segmental errors 33% and (3) Phonotactic ones 20%.

The implications of the above statistics retain the idea that there must be, to some extent, an agreement in pronunciation. Indeed, when making students of English read a list of words without the possibility to distinguish the significance from the context, teachers are often confronted to some pronunciation mistakes that may induce spelling ones such as suffer and gone for sofa and gun. If pronunciation is to vary in non-English speaking countries, it will probably cause a degree of unintelligibility.

However, comparing foreign learners’ level with that of the natives can be discriminatory. Kachru (1986) maintains that the Outer Circle Englishes must be given their autonomy even if it sets aloof from the oldest varieties such as British or American Englishes: “I do not believe that the traditional notions of codification, standardization, models, and methods apply to English any more.” (Kachru, 1986: 29). Conversely, according to Quirk (1981) a standard norm must be kept in those countries. He attacks suggestions such as those of Kachru’s by forewarning of having no standard (such as British or American English) to stick to. Else, it will lead to mutually unintelligible English; the same linguistic phenomenon that happened once with Latin and the Romance languages—the prelude to the fall of the Roman Empire and the death of Latin.

-

The Model Taught in Algeria

Today’s Algerian students of English may become teachers, clerks, participants in international meetings, tourists, or immigrants and they may need to communicate in English. The act of oral communication will fail if speech is unintelligible. It is crucial to use intelligible speech in a period of high technology and of extensive mass media. However, according to Heaton (1988), we can communicate and be intelligible even if our English phonology and syntax are faulty: “People can make numerous errors in both phonology and syntax and yet succeed in expressing themselves fairly clearly.” (1988: 88). British English used to be the model taught to foreign learners of English. Hughes, Trudgill & Watt describe the reason RP is the most suitable accent for foreigners. They explain that it is the most described of the British accents (2005: 3). However, at present, there subsist many other possible rivals, mainly American English.

Some linguists such as Macaulay (1997) emphasise the fact that RP is not widely spoken among its people so why, therefore, impose it as a model in foreign language teaching. Macaulay goes on further, by attacking the use of RP, as to use the Latin expression usually written on graves “requiescat in pace” ‘rest in peace’ (1997: 44). Furthermore, owing to the American show business industry and social media platforms, American English has widespread among the youth. It can be viewed as a matter of fashion to clothe, behave, or pronounce like an American superstar. Such a social and cultural phenomenon is influencing pronunciation and its variation through time too.

Learning more than one English does not necessarily mean that one has to learn all pronunciations or all Inner Circle Englishes. First, it will be too demanding and too exhausting for English learners, then, it will be impossible to learn all English pronunciations with all the socio-cultural attributes they carry. To solve the problem we have to establish criteria for our selection. Therefore, we have to put four underlying assumptions into question:

– What pronunciation has traditionally been taught in Algeria?

– What English is most admired in the country?

– What model do students prefer to learn?

– What English publications are available at the university libraries?

Moreover, students can get confused if teachers have different pronunciations; the same standard ought to be followed by everybody. In Algeria, for instance, British English is taught at state as well as at private schools. In an interview, Louznaji, an inspector of west Algerian schools, states that the variety taught in Algeria is the British one. Even if there is no official decree stipulating the adherence to British English, it is implicitly suggested in English textbooks and via the use of British English that it is the norm to which teachers and learners have to refer to (Ghlamallah, 2007).

-

The Present Study

4.1. Methods

Students of English may prefer one variety to another. But can we really know all Algerian students’ preferences? Since we wanted to know which English variety our university students prefer to learn in class (and not the English variety they prefer to use when speaking to their classmates), a questionnaire was designed. The survey gathered students’ preferences for the learning of one English Standard or more. Data were recorded from 10% of all students of the Department of English—268 undergraduates and graduates.

4.2. Results

The majority of the subjects (64.93%) prefer English RP to other varieties. American English is second only to RP by 31.34%. Among all informants, 1.86% like both varieties, 0.75% favour South African English, and 1.12% have no preference at all. According to these statistics, American English appears to be the only rival to English RP. What is strikingly revealed in this study is that some students prefer RP to American English even if they do not differentiate between the two accents. On the report of the findings, RP is the Standard norm one has to adopt. Indeed, nearly one-third of the population sample (30.60%) claim that they do not make any distinction between RP and any other accent. Among this amount, 62.19% prefer English RP though they claim not to recognise the way it sounds.

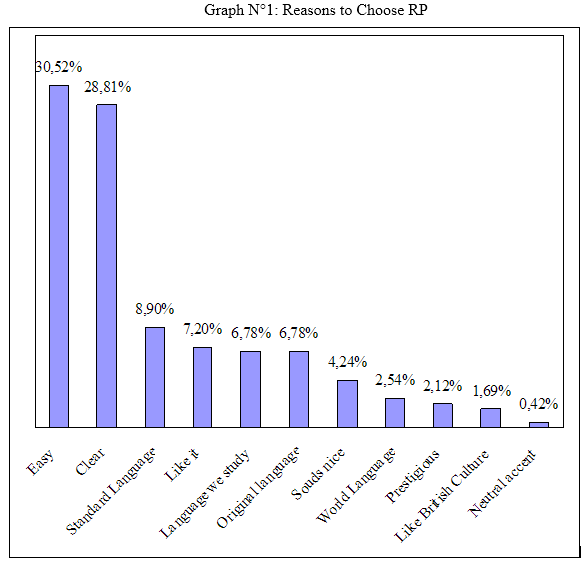

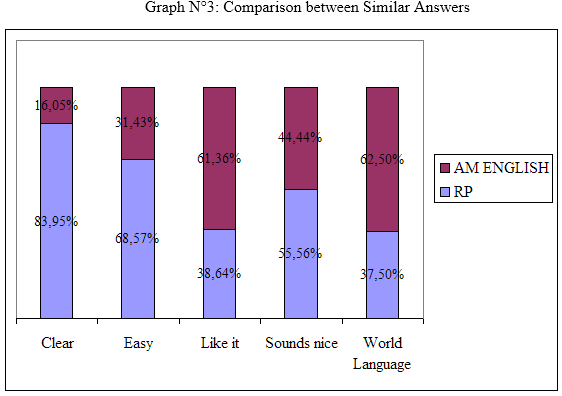

Each participant was also asked to specify the reason(s) of their choosing RP or American English. The following histograms represent all the reasons students have provided when choosing a particular accent. The first two diagrams reveal the reasons in terms of differences. The third one encloses likenesses between both accents.

In relation to the graph above, RP is favoured mainly because it is a clear and an easy accent to learn and to understand—almost 60%. Other reasons were given which are completely different from those elicited for American English. Many think that RP is the only Standard English, i.e. the other Englishes do not have standard varieties at all. In fact, some informants believe that RP is the ‘real’, ‘pure’, or the ‘original’ English; a fact which makes it more valuable and reliable than any other accent. For these students English RP is somehow perceived as a model for instruction.

In the second diagram, the provided reasons differ from those obtained for RP. The differences appear in (1) the number of reasons (8 only) and in (2) the reasons themselves. American English is chosen mainly because of its easiness in learning and its symbolisation as being the attractive accent of so many actors and singers. The latter reason contributes to consolidating the fact that culture and language are tightly linked in the language acquisition process. Such a reason was given only when choosing the American norm. Of course, not all subjects share the same opinion. Others (8.33%) think that American English is a world language and thus the necessity of its being studied. Politically speaking, only 3.33% of the students choose American English because it corresponds to the most powerful country in the world. The remaining students (3.33%) have chosen it because it is a difficult accent, which implies that RP is easier and clearer for them.

The third histogram traces five criteria for selecting an accent over another. The rectangles represent the most common reasons provided by both groups (those who have chosen RP and those who opted for American English). Among the students who have favoured an accent in terms of its being clear, 83.95% prefer RP. We can also notice that in the last criterion, more students 62.5% believe that American English is a world language. To conclude, we observe that RP is principally chosen not because of its social dimensions but because it is perceived as the most practical one. According to these students, it is, therefore, the most suitable and evident norm for academic purposes.

4.3. Discussion

The subjects’ answers need to be taken into consideration when designing curricula and syllabi on account of students’ needs analysis perspectives. Indeed, learning one Standard English is already difficult, and the participants do not seem keen on adding linguistic complexity to their learning. For countries such as Algeria, where students learn English as a foreign language, the choice of the norm should not be based on historical or political relations. What happens, then, if the political agreement changes over time? In addition, students have limited resources of publications to learn all Standard Englishes of the Inner Circle. Students may also prefer one English rather than another not because of its culture but simply because of the availability of reference books in libraries.

The question can be formulated differently, at what stage (when and where) a learner starts learning those Englishes. English teaching in Algeria does not begin with phonetic lessons, and phonology is almost excluded from secondary school curricula. Nowadays, phonetics and phonology are initiated and taught mainly at university (ninety minutes a week). A fact that makes the students’ acquisition (either for adolescents or for adults) be difficult. Children are more predisposed to adopt a native accent than adults are. The latter’s accent can be comprehensible but not inevitably free from any regional or cultural interference or Crosslinguistic Influence unless the learners immerse in an English native speaking land. Indeed, even though proficiency in one Standard English or more requires time, the complete elimination of Crosslinguistic Influence on the pronunciation of English seems impossible.

As this is the situation of English pronunciation in Algeria, students need to do more listening comprehension activities—listen then decode. Such exposure cannot be but advantageous especially when it is planned. English language planning is crucial, and any choice of a particular standard must be under thoughtful guidance and implementation. In fact, choosing freely between rhotic and non-rhotic accents may pose problem first to students as they are left unaccompanied; then to teachers when evaluating as there would be no homogeneity in the classroom.

Usually, such a decision depends on historical associations either with the UK or with the USA, or on the available teaching materials. It may also depend on learners’ abilities, i.e. students can learn, perhaps, the most accessible English for them or the one that is typologically closer to their mother tongue. The sound [q], for instance, is more frequent in some languages than in others. Therefore, speakers of Arabic or of the Romance languages can use a rhotic accent better, whereas speakers of African, Chinese, and Japanese languages can adopt a non-rhotic accent. However, it may be salutary to direct attention to the fact that some people may agree or disagree with such ‘logic’. Arabic speakers, for instance, might claim the need to select a variety according to their preferences. Besides, sharing common features with an English variety does not necessarily entail effective proficiency.

For beginners, students should rather start with one variety, approved by all parties in the teaching/learning process. The teaching of one single norm seems imperative because they can find a mark for reference. Moreover, a presentation of a language with diverse pronunciations from the very beginning can be demotivating. For intermediate students (in a second stage), the teacher can suggest a possibility of alternatives among the most used ones at the same time as the students strengthen their linguistic bases and deepen their knowledge of the language and all the possibilities it offers. This second stage has to represent a phase of transition to the third one (the advanced): during which the teacher proposes a more significant number of varieties. Such introduction will not be, therefore, sudden and unexpected. The students can smoothly view themselves analysing the various uses of the language.

The advantage of such a succession of stages resides in the fact that if such students should intend teaching, they might become less prescriptive (by imposing one single norm) in their daily educational practice. In fact, avoiding or neglecting those standards and varieties can pose problems especially when the teacher labels a different pronunciation as a mistake while, in fact, this very pronunciation may belong only to another norm. The aim is to train students consciously recognise and use at least two Englishes proficiently—such as RP and American English.

-

Conclusion

No Standard English variety (of the Inner Circle) should be neglected when teaching English-language. It would be very interesting and in agreement with Kachru to include in the Algerian academic curricula and syllabi, a subject dedicated to the different Standard Englishes. A learner who knows only English RP, an accent produced by 3% of the population of Great Britain, is by far uninformed of the remaining 97% and of all the other English-speaking communities across the planet. It is no longer a matter of phonetics and phonology but of discovering the other.

During English language acquisition, although the aim to learn more than one standard proficiently might become inevitable, it remains unreal and unattainable according to the current situation and the present results of the study. For, it would entail many challenging targets to achieve. First, teachers need enough qualifications to be able to transmit their knowledge to the students. They cannot accomplish such an objective without frequent and intensive training in English speaking countries to avoid Crosslinguistic Influence from their mother tongue or from any previously acquired language. Next, students need to spend time enough in language laboratories to be capable of discriminating between those accents. Then, the condition that must be fulfilled before the target can be achieved is the availability of enough materials and well-equipped laboratories for teaching.

After several years of English studies (from school to university), the majority of the students sample still cannot master one single Standard English yet, even if they prefer learning RP English. Therefore, it is more relevant to adhere to one standard than to try to master them all. Still, a distinction needs to be made between recognising a language and mastering it. The problem would be solved if students could master one Standard and be able to recognise major features of some others. Finally, the question of which Standard English should be taught at schools needs to be pondered on; otherwise, Algeria might find soon itself with a lingua franca, namely Algerian English.

References:

CAMERON, D. (2012). The Commodification of Language: English as a Global Commodity. In T. Nevalainen & E. Closs Traugott (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the History of English (pp. 352–361).

GHLAMALLAH, N. R. (2007). Phonetics and Phonology of Standard Englishes in the British Isles, the USA, Candada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Unpublished Magister Dissertation: University of Oran.

GÖRLACH, M. (1990). Studies in the History of the English Language. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

GRIFFEN, T. (1991). A Non-segmental Approach to the Teaching of Pronunciation. In A. Brown (ed.), Teaching English Pronunciation: A Book of Readings. London: Routledge.

HEATON, J. B. (1988). Writing English Language Tests. London: Longman.

HUGHES, A.; Trudgill, P.; Watt, D. (2005). English Accents and Dialects: An Introduction to Social and Regional Varieties of English in the British Isles. London: Hodder Arnold.

JAMES, C. (1998). Errors in Language Learning and Use: Exploring Error Analysis. London: Longman.

KACHRU, B. B. (1986). The Alchemy of English. Oxford: Pergamon.

LEATHER, J. (ed.) (1999). Phonological Issues in Language Learning. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers.

MACAULAY, R. K. S. (1997). Standards and Variation in Urban Speech. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

McARTHUR, T. (1987). The English Languages? In English Today 3(3): 9–13.

QUIRK, R. (1981). International Communication and the Concept of Nuclear English. In L. E. Smith (ed.), English for Cross-Cultural Communication. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

TIFFEN, W. B. (1974). The Intelligibility of Nigerian English. Unpublished Dissertation: University of London.

WILKINSON, J. (1995). Standard English and Standards of English. In R. Carter & D. Nunan (eds.), Introducing Standard English. England: Penguin English.

1 The Scottish accent is often referred to as being ‘nice’ or ‘singing’ as in: “I recognized the singing speech of Glasgow.” By W. Somerset Maugham (1971): Collected Short Stories 1 “A Man From Glasgow.” G.B.: Nicholls & Company Ltd. P 368.