Dr. DJALAL Mansour

University of Frères Mentouri, Constantine, Algeria

Abstract

The present paper has sought out to furnish research-fed accounts on the glaring myths and striking realities all bearing on the prophesied viable applicability of the competency-based approach in EFL English classes where most recipients of the linguistic input are widely referred to as lower-ability performers by local practitioners. We, for feasibility rationales, opted for secondary-school classes teachers, novice as well as fully-fledged, to be providers of the requisite data wherewith we could arrive at satisfactory answers to the three primary questions our undertaking has grappled with: 1) Do teachers genuinely have at their pedagogic toolkit disposal sufficient grasp on the various trappings of this contemporary approach; 2) Do they run into predicaments that make them convinced that this approach is more of a hindrance than an asset to triumphant learning; and 3) Do they bend, out of sheer experience and commonsense, to the inevitable conviction that explicit teaching is the best way forward? To glean adequate data for our research undertaking, we tailored and administered a semi-structured questionnaire to seventeen secondary-school English language tutors. The overwhelming bulk of the amassed data have yielded a wide range of insightful findings all of which pointed to one unified conclusion: in the local secondary schools the merits of this approach are far outstripped by its virtually countless demerits. We have, in the same vein, inferred that the local pre-university academic community is in desperate need for explicit-instruction approaches to language teaching: wholesale application of competency-based approach does serve to perplex the learners. Therefore, the local researcher province does actually cry out for further scrutiny of this state of affairs for tailoring an approach that does not alienate our learners. It’s high time we abstained from importing educational policies which have proven to deliver outstanding outcomes beyond our country’s borders. An a priori remolding of the approach is a must that stares us all in the eye.

Keywords: Competency-based Approach; Secondary-school Teachers; Explicit Instruction; Language

Introduction

The educational sphere has never ceased to witness the coming and going of an endless range of innovations and inventions and creative pathways. All these issues have come into being due fundamentally to one overarching factor: teachers and curricular planners are constantly in search of better and more fruitful avenues for the ultimate attainment of better success scores. Arguably, whenever a new method or approach endeavors to prove its maturity and its capacity to iron out the thorniest of issues that earlier approaches and methods have not been adequately capable of doing, it strives to bring into question the fragilities and virtually endless shortcomings that its proponent approaches are notorious for. One is intrigued by the enormous criticism leveled at traditional approaches to the drastic point where one starts to doubt that pioneers of novel approaches have themselves received instruction under their own approach or method when they were learners themselves, which is intuitively untrue. The present paper will look at a number of facets with regard to how competency based approach to language teaching has been handled and rated in the Algerian secondary school setting. It will attempt to cast light on some of the hidden truths characterizing the actual predicaments that teachers run into whilst trying to implement this approach. We will try at various junctures of the paper when dissecting the results of the research tool deployed to bring to the light of day some of the gateways that ought to be more amply explored for attaining a better application of the approach. The paper starts out by addressing a set of properties that the scholarly literature on offer has furnished over the years.

Competency-based Instruction

This approach has been in existence for nearly six decades now. Its raw ideas emanated from the behaviourist school of thought. It first emerged in the United States in the 1970s and it was initially adopted for the designation of vocational training programmes. In its early days, it was not meant to be deployed in the school settings. However, as its viable applicability started to generate praiseworthy outcomes, the scope of its plausible expansion started to gradually widen and expand. A decade later, this approach, although it was still in its infancy stages, it reached the Continent and nearly a decade afterwards, it started to get employed in a range of Australian professional spheres (Bowden, 2004).

Competency-based approach (henceforth CBA) has a number of characteristics which together impart all the uniqueness that the approach as a whole enjoys. If one considers only one constituent of this approach in seclusion of other ones, they are prone not to arrive at a fuller picture of how the approach actually works and how dissimilar it is from other approaches. CBA syllabus is based on a priori needs-analysis of the students (Richards and Rodgers, 2001). This might be taken to entail that there are no ready-made syllabuses to be used for all batches of learners and that it is learners’ needs and expectations and actual knowledge-to-skill competencies that determine to a great extent what category of lessons to incorporate into the syllabus and what lesson sequencing to adopt for any particular class of learners.

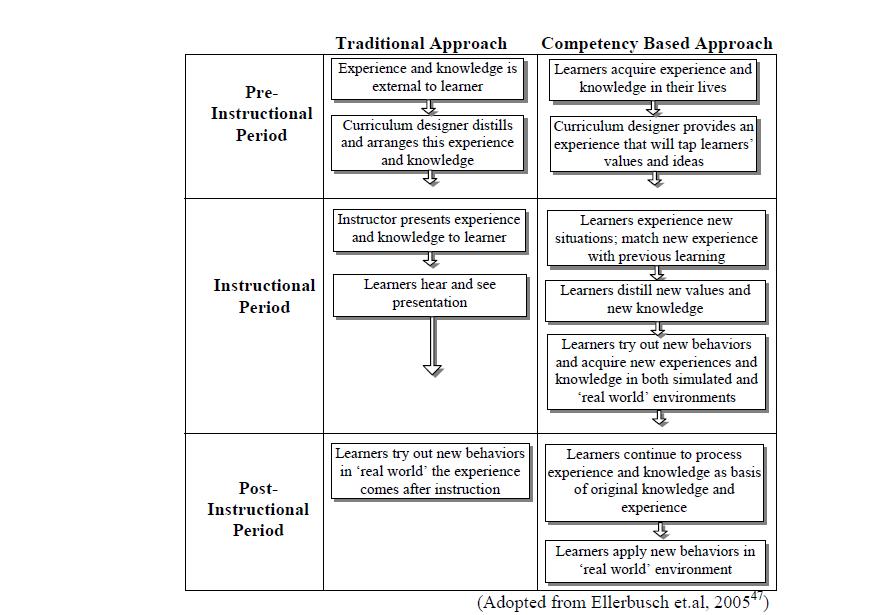

One of The defining tenets of this approach is that it is, as Sturgis & Patrick framed it, ‘the transformation of our education system from a time-based system to a learning-based system.’ (2010, p. 1) For these co-authors, transition from one set of lessons/tasks into another is not time-bound. Learners are taken into newer sets of lessons, once competencies set for the current lessen have been adequately fulfilled and proper mastery has been accomplished by the students enrolling in the program. This contention is corroborated by O’sullivan and Burce (2014) as they explicitly maintain that, ‘The most important characteristic of competency-based education is that it measures learning rather than time. Students’ progress by demonstrating their competence, which means they prove that they have mastered the knowledge and skills (called competencies) required for a particular course, regardless of how long it takes.’ (p. 72) These scholars go on to comment that what this approach holds dear is that the set competency gets mastered irrespective of how much time this might actually take up of the courses lifespan. It is fair to argue, following their footsteps, that this approach is competency-bound and progression from the current into the new lesson on the course agenda is dictated exclusively by learners’ satisfactory command of the present competency. According to these co-authors, it is the absence of time-constraints that enfeebles the prosperity of even the most professionally tailored course, that sets the CBA and other approaches apart. This is evidently discernible in the conclusion that they drew, ‘So, while most colleges and universities hold time requirements constant and let learning vary, competency-based learning allows us to hold learning constant and let time vary’ (O’sullivan and Burce, 2014, p. 72).

Admittedly, the competency-based approach is different to traditional approaches as it opens up the door for learners to expand their learning opportunities beyond the classroom setting. This is probably what Sturgis and Patrick are trying to get out here, ‘Without a competency-based policy framework, they are unable to take advantage of the full potential of online learning’ (2010, p.1).

Competency-based Language Teaching

This approach (generally shortened to CBLT) is an attempt to generalize the application of competency based approach to the realm of foreign and second language instruction (Richards and Rodgers, 2001) What is noteworthy about the early stages of its implementation is that it was not used by state’s national curricular systems; it was only used for immigrants and refugees-oriented language programmes. CBLT gained popularity and recognition in the US by the 1990. This is clearly borne out by the fact that most refugees, who sought to be recipients of federal financial help, were literally compelled to attend schools whose programmes were built upon the innovative ideas and roadmaps set up by advocates of this newly emerging approach (Grognet & Crandall, 1982).

Crucial to a thorough understanding of the trappings of this approach is that its chief underlying philosophies are rooted in the interactional, functional nature of language. That is why it is said to be inextricably bound and commonly associated with communicative language teaching. This is the basic reason why this approach seeks to equip learners with the various sets of skills and competencies that they will need to function in accordance with societally accepted norms of language usage. For advocates of this approach, mastering the formal features of language is by no means sufficient and even the most exhaustive command of such non-functional knowledge of language does not denote that learners have attained the requisite competencies hereby they can engage successfully in real-life language use scenarios. Broadly speaking, a competency could be loosely defined as the practical skill that the learner has picked up in class and which enables them to interact with interlocutors in social contexts akin to the ones for which the course they enrolled in was designed. This is the basic reason why van Ek (1977) opted for labelling the syllabus guiding CBLT settings as ‘a behavioral syllabus’ since it encompasses a definite set of performance skills to be got the hang of throughout the teaching span and all the materials and activities deployed are there to serve this particular objective.

2.1 Roles of Teachers within the CBLT Framework

The distinctive prominence of this approach is evident in the roles it assigns to teachers. The teachers have been relieved of a great deal of what they would do when functioning under the frameworks of other approaches, since a great deal of class time and effort is shifted to the students/learners. This is the chief reason why this approach to teaching falls neatly into the learner-centred genres of approaches and it is indeed the most widely applied one worldwide. Instead of being a filler of knowledge vessels that learners come into the classroom with, the teacher becomes more of a facilitator of how these vessels could be filled up mainly by the learners as they get actively immersed in the process of language acquisition (Sturgis & Patrick, 2010). Learners’ roles are no longer those of passive recipients of instruction and drills which they are supposed to rehearse. Rote learning is overshadowed by other tasks where they are active participants and for the fulfilment of which they make adequate personal efforts without constantly taking recourse to the teacher. The centrality of the teacher’s role lies in their ability to construct tasks and activities which will serve to meet the needs and expectations of the learners previously calculated prior to the commencement of the course. A portion of the teacher’s role bears on their constantly giving properly devised feedback and in adopting appropriate measures for assessing their students’ progress. (Richards and Rodgers, 2001)

2.2 Roles of learners within the CBLT Framework

This innovative approach to language teaching has not only brought about drastic alterations to teachers roles, students’ roles have also undergone significant shift. Students, within this framework, are no longer recipients and consumers of knowledge furnished by their caring teachers on a silver platter. Students are called upon to take charges of their own learning and to be active participants in the classroom. Their roles will be to generate knowledge and share it with their partners. (Jones, et al., 1994) This approach staunch advocates contend that without rendering learners fully autonomous, the learning outcomes would not match the mutual expectations of both teachers and learners.

(as cited in Rambe, 2013, p. 51)

Methodological Procedure

To answer the research questions raised at the outset of the study and glean an overall teacher-furnished assessment of the extent to which CBLT is fruitfully applied in and adequately suitable to the various needs and expectations of Algerian secondary schools students, we have opted for using one teacher’s questionnaire. The questionnaire composition has been varied in such a way that we could gauge a wide array of facets pertaining to some defining facts of CBLT application. The questionnaire has been segmented into four main partitions each of which has been devised to disclose for us the following:

-

To what extent are the practicing teachers cognizant of the ins and outs of CBLT?

-

How geared up are they to implement it in conformity with what proponents of this approach prescribe for it to be triumphantly applied?

-

Is the classroom atmosphere a fertile terrain that empowers teachers and students alike to function adequately in a CBLT environment?

-

Are the students’ needs, weaknesses and expectations taken into consideration by syllabus designers?

Population and Sampling

The participants pool that we have opted for to take part in our study are secondary school English language teachers. Although, the competency based approach is applied or recommended to be so by the Algerian ministry of national education at all grades starting from the elementary school grades onwards, I wanted to get to the bottom of the specificities that hallmark its application at the secondary level. This is primarily because this is the only level with which I am most sufficiently familiar since I have been a teacher for nearly four years now. Being an in-service, non-novice teacher would entail that you are in a far better position to ask the more pertinent questions that a complete outsider and that you are far more likely to analyze the findings in the light of what you already know about the status quo of teaching at the secondary level locally. I am adequately failure with syllabi content of the three secondary school grades since I have taught all the three grades. I initially considered administering the questionnaire to teachers of English French and Arabic and even those of German and Italian, but I stopped half way through this process. After all, the CBA could be better suited to the Arabic subject tuition modes due to the various characteristics and specificities of the Arabic class and the same would as it would not apply to other languages taught locally at the secondary level on account of this reason or other reasons bearing even on the nature of the activities and the overall syllabi compositions of those subjects. I ended up realizing that investigating how this approach is applied for the tuition of English would be the safest and most rewarding way forward. Seventeen teachers have taken part in my study. As is customary about questionnaire administration, I administrated the questionnaire to a much bigger number of potential participants but only seventeen handed in their completed versions thereof. It is probably worth mentioning that only one questionnaire was handed in and filled in while the participant was physically present. All the other teachers were sent the questionnaire electronically and it was delivered via the same channel.

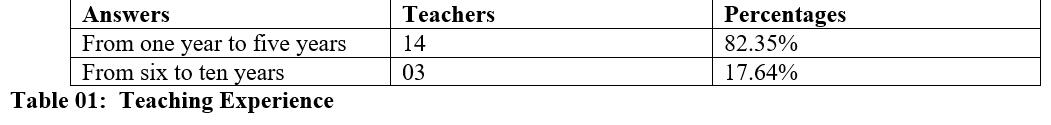

01) How long have you been a teacher?

Most of the teachers that completed the questionnaire have not have a considerably long experience in the field of language teaching. Over eighty percent of them have not taught for more than five years, whilst the remaining has taught for up to ten years. It is fair to argue that the overwhelming bulk of the participating teachers got into the profession after the reforms had already put in place. They, therefore, do not own first-hand experience of what teaching under a learner-centered approach entails and what particular pros and cons this teaching modality is notorious for and what it promises to deliver. They, however, are better suited to filing out this questionnaire since what we have sought out to unravel are the facts and fictions related to the applicability of the competency based approach to language teaching in government schools in Algeria. After all, this approach has been adopted for the tenth year now and our aim has not been to get to the bottom of the areas of strength and those weakness of traditional approaches and contemporary ones.

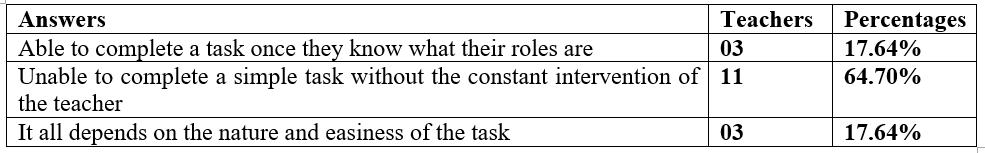

02) Are your students

Table 02: Teachers’ Estimates of their Students’competence

Data displayed in this table attest to one overriding ffact with regard to learners’ capacity to function well in class and do the various assignments that the syllabus requires them to do. The inference that could immediately be drawn out of this data is two-fold: either the content of the syllabus are way beyond learners grasp or learners are very weak that the even the simplest basic activities give rise to insurmountable problems for them that they fall short of completing the assignment on their own without teacher’s constant intervention. Another major deduction that could be calculated is that most teachers find themselves constantly reverting, presumably against their professional will, to traditional ways of teaching where the students are playing the role of sheer recipients of input and the teacher is the knowledge dispenser unit.

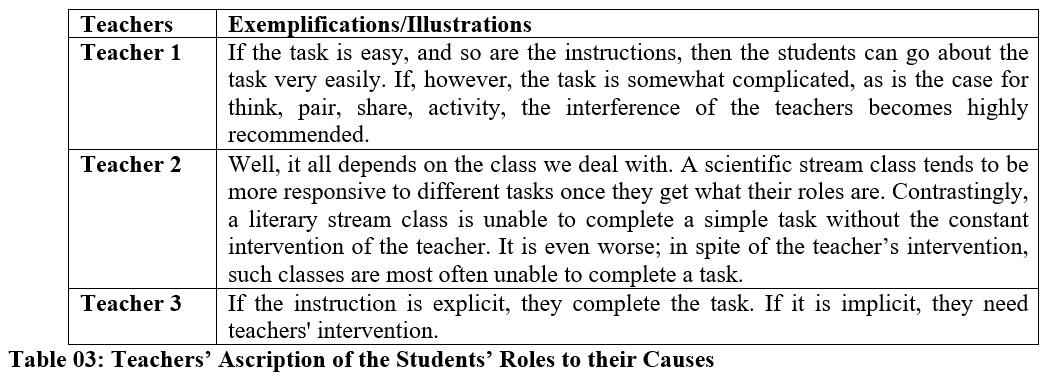

03) If your answer is “c”, could you please exemplify and elucidate

As this table demonstrates, some teachers would contend that students’ responsiveness depends largely on the nature of the task as such and on the stream to which the students belong. Put in plainer wording, students are more willing to interact and be responsible participants in the process of ideas-making and ideas-sharing, which is what a quintessentially CBLA lesson would look like, when the assignment is hallmarked by explicitness. Therefore, all the tasks that would necessitate that learners make deductions and inferences out of a set of lesson information, they are less likely to be engaged and to take charges of how the task unfolds thereby propelling the teacher to constantly step in or else the lesson would get halted and even the slightest amount of learning would not take place. It could be recommended, based on these findings, that the number of deduction-based classroom assigned gets reduced. After all, the overriding objective of any lesson is to empower learners to come to grips with newer bits of linguistic insight. If the lessen is far beyond their reach, then this practice would utterly defeat the purpose. Probably some students’ outward rejection of learning languages in Algeria could be put down to the fact that the genre of the lessons does not fit their expectations and their rather non-existent linguistic command that they eventually end up developing academic defeatism. Such a perilous academic attitude will be virtually impossible to reverse at the secondary school.

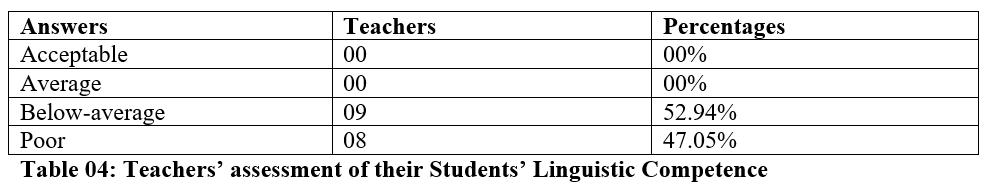

04) How would you rate your learners’ overall command of English?

Competency based approach to language teaching has high expectations in students preparedness to take charges of what goes on in the classroom and to be responsible at least partly for monitoring their on progress. Lower-ability students, who possess only little linguistic knowledge are less likely to function well and fulfill the requirements of how this approach works. This table exhibits that the overwhelming bulk of the students are lower-ability ones. By implication, it is no wonder that these students do score poorly in end-of-term local English examinations and at the national Baccalaureate examination as well. The syllabus content is unduly overly ambitious and its content does not, as a rule, lend itself to easy strain-free assimilation by the students.

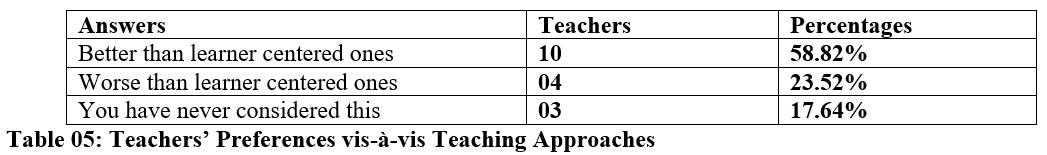

05) In your perspective, are teacher-centered approaches to learning

This question was devised to get to the roots of teachers’ overall reactions to the two widely in application. It is indeed what characterizes teachers convictions and gauges of what would make learning successful and would impede it that determines to a great extent how they would go about their day-to-day manifold tuition duties. A bug majority of the teachers are, as the data depicted in this table attest, not remotely against CBLT approach. Therefore, it is legitimate to argue that the failure nationally recognized with regard to students’ score cannot be translated in terms of teachers’ rejections of the approach as such. A profounder scrutiny of teachers’ own knowledge concerning how to professionally apply this approach is in order. Endorsing the convictions entertained by proponents of this approach does not inevitably entail that most teachers are capable of successfully applying it simply and purely because without sufficient training on how to better implement this approach would render even the most staunch of teacher advocates certified losers.

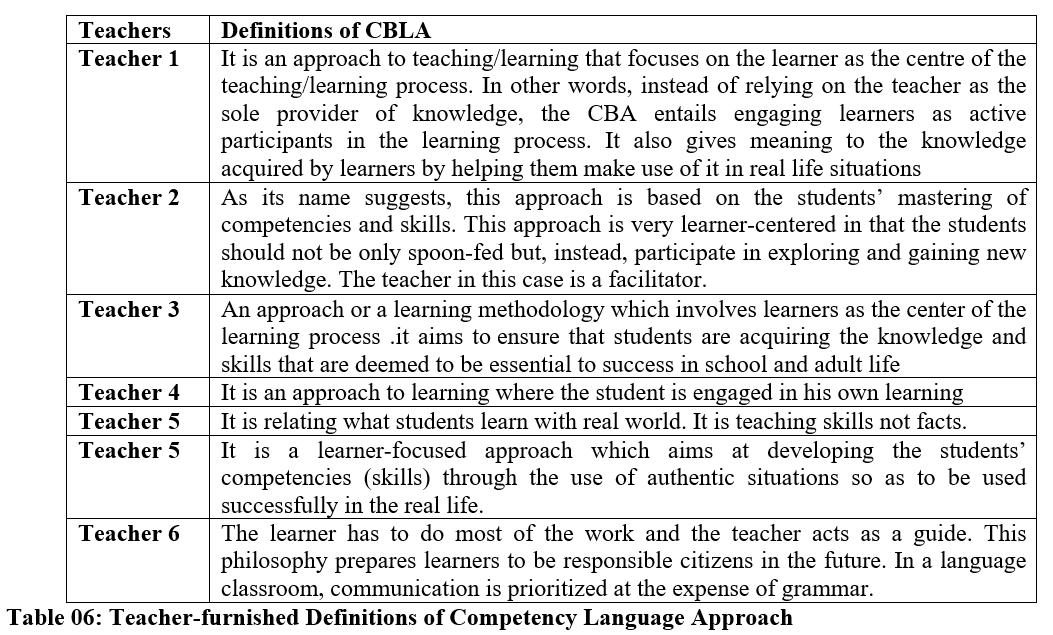

06) Can you provide a short definition of competency-based approach as you understand and try to practice it in your classroom?

As is immediately patent from this table, not all teachers gave definitions of the CBLT. The six teachers’ definitions, however, are upon the whole valid ones although some of them lack precision and clarity owing predominantly to their brevity. One of possible interpretation one could put into the other teachers’ failure to furnish a definition is that they do not have a sufficiently mature understanding of what hallmarks this approach. Some of the upcoming discussions will lend ample confirmation to this inference.

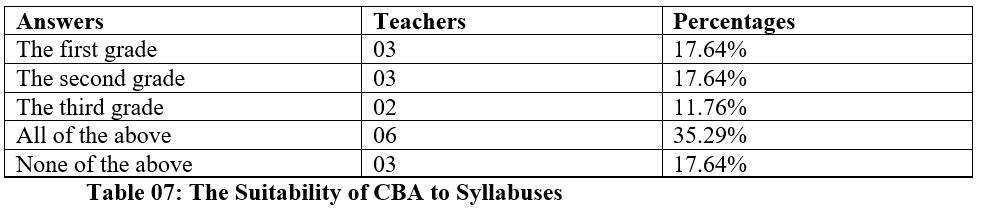

07) Which secondary school grade syllabus is the CBA more easily and more fruitfully applied for:

Since the textbooks designed for the three secondary school grades do exhibit a wide range of feature and component differences (the designers thereof are not the same authorities in the field), we wanted to find out which textbook and which grade seems to be a better terrain for CBLT to meet a fertile application-fostering environment. Teachers do appear to portray a non-unified picture regarding the suitability of the syllabi of the three grades to CBLT approach. There is not a common consensus aongst them, however. The biggest percentage of teachers do concur that the three grade syllabuses fit the requirements of the CBLT approach. The inference tht we could arrive at aided by these mixed responses is that: 1) only some of the syllabuses in use are better designed to fulfill the requirements and maxims of CBLT; 2) the teachers, on account of their being not adequately trained to implement this approach, failed to deliver the content in accordance with this approach’s teaching roadmap; 3) due the very low level of students’ performances, teachers (despite the strenuous efforts that accompanied their jobs) ran into greater than tolerably handled numbers of predicaments that they ended up judging the syllabus as such as being not tailored in accordance of with CBLT approach’s guidelines: this approach necessitates that designers of teaching materials pay especial attention to learners’ needs, current linguistic competencies and expectations.

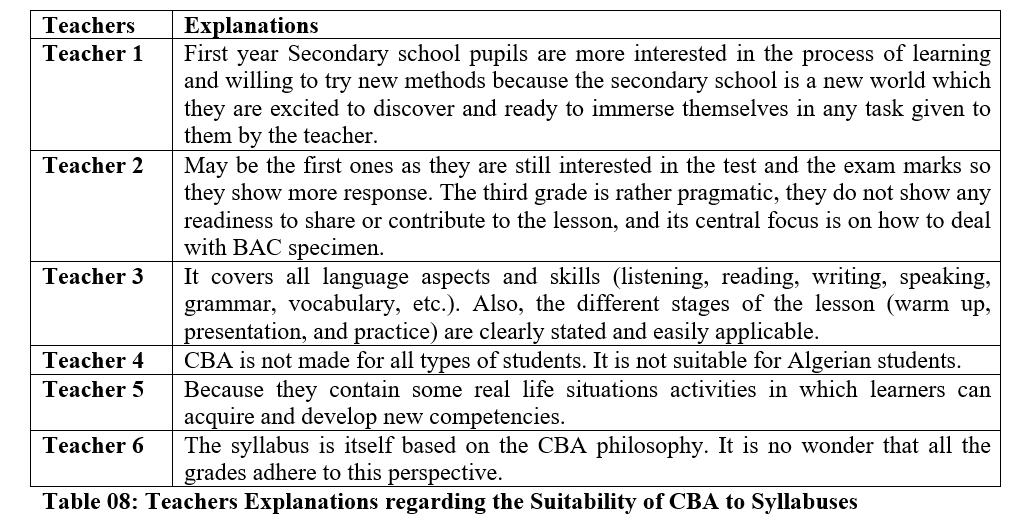

08) Can you provide some explanatory accounts for your choice?

As is evident in this table, different teachers have come up with different interpretations into why they hold the convictions disclosed in their answers to the preceding question. The most extreme of persuasion that this table depicts bears on the fact that one teacher entertains the belief that CBLT is downright unsuitable to the Algerian students. Indeed, it would fairly sensible to argue along the same lines if one happened to function at a school environment where most students demonstrate a drastic shortage of even the most basic of linguistic skills. As the forthcoming discussions will reveal, some teachers, who have been teaching at rural areas, complain that this approach does violate the expectations and flout the needs of students in a number of diversified ways. A glance at the content of some of lessons taught would unravel why such teachers have come to adopt this stance towards the approach. Most of the lessons, be they grammatical, phonological or otherwise, have been erected on the major presupposition that the learners get into the classroom already mastering a wide array of linguistic skills that would empower them to comfortably cope with the activities and assignments that they are required to perform.

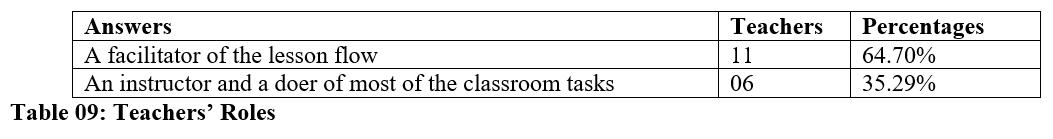

09) Your role in the classroom is that of:

A big majority of the teachers said that their roles in the classroom is that of a facilitator; only a few of them answered that their role was that of an instructor and a doer of most in-class assignments. These answers might not flow together with previous and next answers into the same conviction stream. Some of the teachers, at times a smaller majority at other other times a bigger one, claim that this approach does not fit the Algerian setting while here a big proportion of teachers describe their roles in the classroom as being facilitators and supervisors of the learning process. Such roles are typical of CBLT environments. When viewed from a different vantage point, which appears to allow for a better translation of the overt inconsistency of their answers, teachers strive to comply with the guidelines and codes of practice the approach stipulates. Their attempts and all the efforts that they put into adhering to this approach’s instructions do backfire since they cannot get their students to do likewise. They, therefore, find themselves constantly obliged to revert to the traditional modes of lesson delivery.

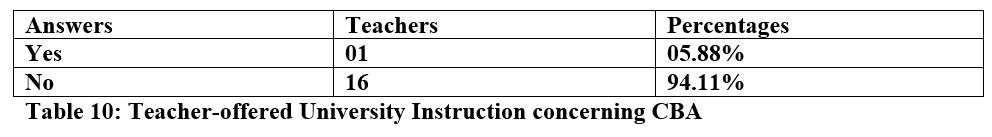

10) Have you received enough instruction during your BA and or MA programme regarding the CBA specificities and ways of its application?

This table shows that the overwhelming bulk of the participating teachers had not received any university training to do with CBLT approach. This would entail that unless these teachers make personal efforts to get the hang of the defining characteristics of this approach and how it could be effectively implemented, their ability to teach well using a syllabus constructed following this approach’s guidelines. It would, likewise, demonstrate that university syllabuses does not furnish the prospective teachers with ample theoretically as well as practically oriented content that would eventually serve to render them sufficiently empowered to take up their duties with ease. Presumably the university curriculum has not been upgraded and updated to echo and match the novel educational reforms enforced by the national ministry of education. The only teacher who answered in the affirmative seems to have been a graduate of a teacher training school since it is overwhelmingly at such governmental institutions that teachers receive adequate training about how to function properly and conveniently in the school environment. Needless to say, we are not recommending that university training and training at teacher training schools be made identical in terms of the curricular content. What we are trying to get out here is that more attention should be given by syllabus designers to incorporate some units into the syllabuses of at least one module that would enlighten the teacher-to-be about the new requirements and duties that await them at the professional setting where some of them will end up functioning. University training is bound to make students, prospective teachers, more ready to face up to the multifarious oft-daunting challenges that lie ahead of them when they step into the professional gate. We maintain that the lesser pedagogic-oriented university training students get at university, the less prepared they are to contribute to the prosperity of the school life no matter how strenuous the effort syllabus designers have put into tailoring the learning input. Moreover, the university training content should be devised in a such a way that government school policies are well and truly incorporated into the academic content. If no homogeneity is struck between the theoretical input students receive and the classroom assignments that they will end up supervising and mentoring, the usability of the university curriculum must come into question and alterations should be put in place.

11) If your answer is “yes”, in what ways has this academic training prepared you for real life classroom practices?

-

Teachers

Explanatory accounts

Teacher 1

It helps me design lesson plans that contain different tasks and activities in which learners are involved actively in the learning process.

Table 11: The Academic Instruction Value regarding CBA Implementation

The only teacher who said that they had received academic training at university do corroborate our above sated arguments. This teacher explicitly states that the training has endowed them with insights into how to prepare assignments that would enhance students’ engagement in the classroom. Teachers who have not received such training would potentially be less able to prepare engaging activities despite their best of efforts.

12) Have you received instruction on how to teach within the CBA framework in your pre-service training courses?

-

Answers

Teachers

Percentages

Yes

13

76.67%

No

04

23.52%

Table 12: CBA and Pre-service Training

Pre-service training does play a hugely empowering role to prepare the teachers for the nature of the professional challenges that they will later experience heads on. In the Algerian context, such genres of training courses are typically supervised by inspectors and very occasionally by teacher trainers. This question sought out to see if in this courses, the teacher went through training sessions where they were taught about the ins and outs of this approach and what is required of the to do to satisfactorily adhere to the rules and practice modes and priority scales such an approach prescribes for them. The data shows that a great majority of the respondents did receive such form of training. It is to be noted, however, that this rather generic question was set primarily to pave the way for a profounder question: the precise nature of the training content that the participants received.

13) Was the training course you were offered practically-oriented

-

Answers

Teachers

Percentages

Yes

02

11.76%

No

15

88.23%

Table 13: Nature of the Professional Training Received

Most of the teachers participating at our study attest that the training courses that they were offered during their preliminary professional training session were not practically oriented. It is no wonder, therefore, that many of the teachers still blame the approach’s suitability to their own learners. Teachers have not been introduced into how to implement it into their teaching. Being besieged by a wide range of duties inside and outside of the classroom may not have allowed them sufficient amount of time to explore for themselves how this approach could be applied with reassuring success rates. It is, in the same vein, imperative that inspectors and all those academics and professionals reconsider what to incorporate into such highly crucial professional training sessions. They should refrain from depending on the old ineffective approach which encourages undue reliance upon instructing the trainees about the various properties of a given teaching practice and how this practice has been applied at non-national academic settings. Teachers should be adequately exposed to how this approach could be applied at or schools with our learners and abiding by the textbook guidelines and syllabus objectives.

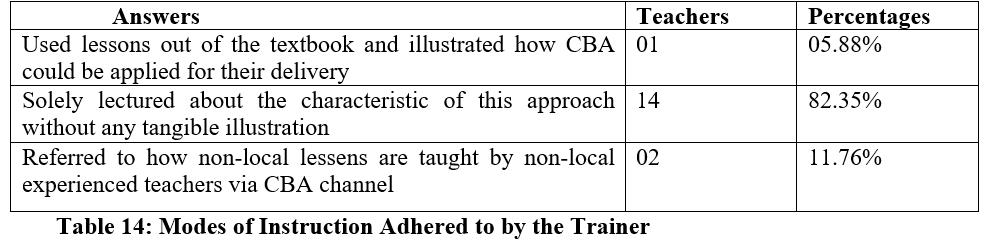

14) Has the educational expert (the inspector):

What this table depicts is that the overwhelming bulk of the participants answered that the instructional content taught at training courses was theoretically oriented while such incredibly crucial phases of professional development do genuinely call for exposure to practical data. The newly recruited teachers should not be expected to step into their new jobs knowing precisely what to do and where to go. Colleagues at the same school may not always be willing or able to offer guidance when the new teacher runs into daunting problems they cannot sort out on their own. Therefore, it is vital that inspectors and trainers lay the groundwork of what teachers are primarily going to do to be productive agents in their respective teaching environments. Focusing on theoretical aspects of CBLT will doubtless not offer sufficient assistance to the novice teachers who need to be shown the ropes by their leaders in the field. Theoretical content could be downloaded at the click of a button and teachers could learn on their own about this approach, how it came into being, its merits and demerits, how it has been applied in such and such a country, etc. It is indeed how this approach has been applied locally that should constitute the content of this preparatory training sessions. There is indubitably a great deal to share with the novice teachers on this front and it is this category of training content that they are eager to receive.

15) Are you still being constantly updated at training sessions about better ways of implementing CBA locally?

-

Answers

Teachers

Percentages

Yes

00

00%

No

17

100%

Table 15: Ongoing Professional Training Teachers Gain

This table shows that none of the respondents have received updates on better ways of implementing this approach. A teacher who started back in 2008, therefore, does not know about the new areas of expansion that this approach receives. They have not benefited from their fellow teachers’ insights into how they have coped with implementing this approach at their individual school environments. Inter-teacher variability with regard to how this approach has been applied and what hurdles they encountered, what shortcuts and tactics they managed to uncover for fulfilling the lesson’s needs and suchlike are of paramount importance to the professional community’s success and learners’ academic wellbeing. It is indeed through constantly exchanging practical ideas gleaned right from the teacher’s own quotidian professional lives that everyone will eventually develop a more fertile and mature understanding about how this approach works and how to reduce the anxiety and uncertainty widely associated with implementing this approach.

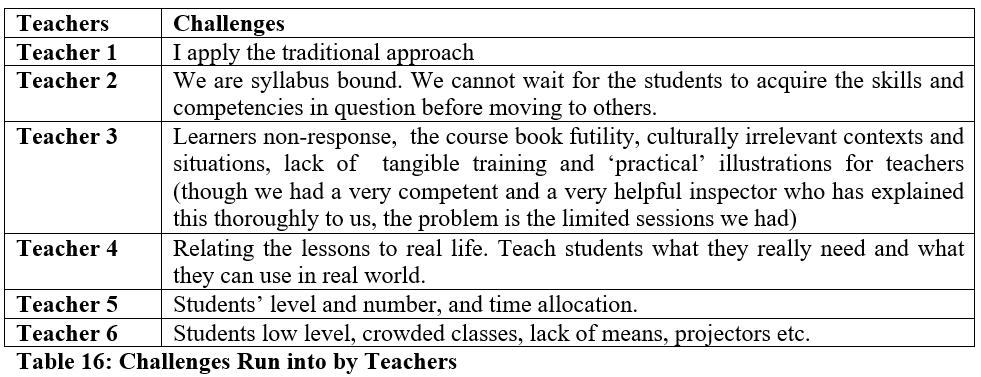

16) Could you mention some key challenges you have run into in your daily efforts to implement the competency-based approach?

In this table, a number of factors that have been already discussed come up. One of the teachers has raised a highly vital issue, though. They talked about the futility of the course-book. For them, the futility lies in the cultural unsuitability of the units’ content. They seem to have tied this factor with the oft-observed and oft-reported students’ lack of responsiveness. Probably the students, who find thi cutrual context rather alien to them and/or a content that they would not love to acquire or get exposed to, they develop rejection which triggers off reluctance to participate and perform their varied roles in class. Another issue of paramount relevance and importance is discussed, albeit briefly by another teacher; teachers are syllabus bound. Indeed, teachers at the three grades, and especially of the final grade, are required to cover throughout the scholastic year all the units that the syllabus contains. Failure to abide by this requirement might make the teacher subject to some punitive measures. The teachers’ incessant worry to attain a full coverage of the syllabus is all the more heightened if they happen to teach Baccalaureate students. This is exclusively because these students will sit a national examination and all students across the country should have learnt the same lessons. Teachers, therefore, find themselves slaves to the syllabus. This will not make them fulfill one of the most intrinsic conditions of this approach: students will go up the competency ladder when and only when the current competency has been satisfactorily mastered and the teacher manages to procure enough cues that this is the case. Being syllabus bound literally forbids or bans this practice. This becomes all the more so when most of the students -as the foregoing teachers testimonies show) are lower-ability ones who have not got the hang of even the simplest of linguistic rules.

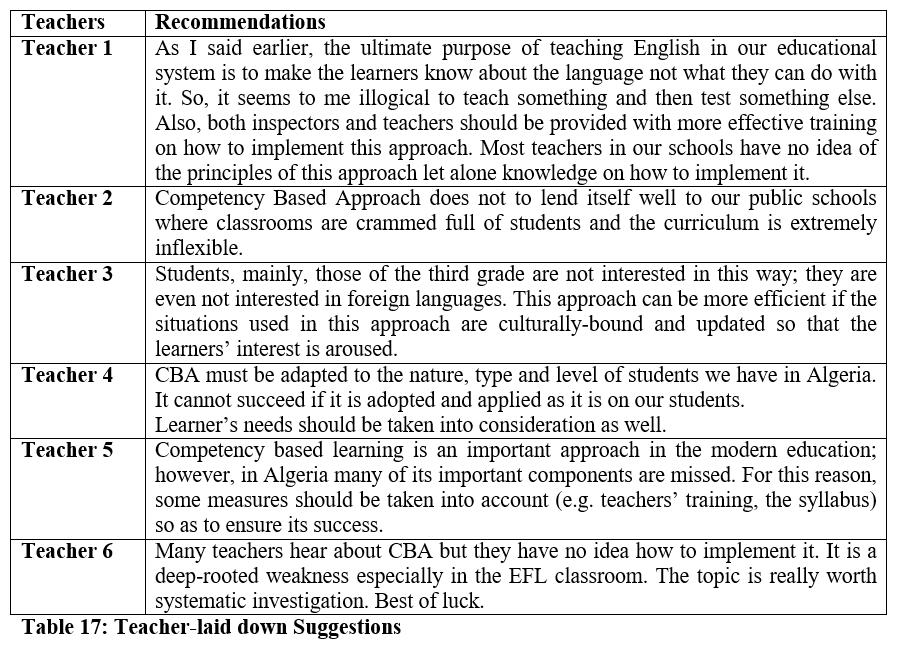

17) Can you kindly take a few minutes to add a few comments or recommendations which might contribute in the ultimate pedagogic suitability and usefulness of the finding of this questionnaire?

Virtually all teachers diversified vantage points and recommendations that this table portrays have been looked at while discussing the above questions. So, this last question did not get us into noel discussion avenues that the foregoing questions did not pave the way for. This, however does by no means imply that data represented in this table is dispensable or too superfluous to warrant any in-depth scrutiny. Far from it. Probably the teachers kept deliberately reiterating some of the major challenges and hurdles that, they believe, impinge upon the stress-free applicability of this approach. They wanted to underscore for us the glaring fact that CBLT is truly very difficult to readily implement and for this to be reversed, a plethora of alterations ought to be put in place. Some, as is evident, revisited the discussion of the unquestionable value of practical training for the implementation of this approach to be a less daunting, more straightforwardly understood mode of instruction. After all, unless teachers get empowered about how to adequately implement this approach, reforming the syllabus will be of practically non-existent value.

Conclusion

The suitability of competency based language teaching in Algeria to the secondary school students’ needs and expectations has constituted the starting point of the research enterprise reported on in this article. This approach was introduced by the ministry of national education to ease up the burden that parents and teachers alike have been carrying with regard to learners’ low levels of academic proficiency and competence. After all this approach has generated it praiseworthy outcomes in many countries up and down the globe and it has increasingly been upgraded and newer modes of its application have been tailored. We cannot justifiably maintain that it is still in its infancy and no strong educational system should venture to introduce into the curriculum. CBLT literature is replete with copious instances of educational settings where its implementation has been truly successful and where very little challenges stood in the way.

This investigation has unveiled a quite a profusion of rather worryingly daunting facts associated with a fruitful implementation of this approach locally. The inferences tht thi study has yielded are many fold:

-

Members of the teaching profession locally are not adequately acquainted with the strategies and rules of proper practice that this approach necessitates for its application to bring about the sought outcomes. This lack of preparedness, by implication, constitutes a huge barrier and renders their practices fraught with departures from this approach’s norms and code of decent practice

-

During their academic university training or during the pre-service pedagogic courses that they attended, the teachers received very scanty ineffectual training with regard to how to effectively put the guidelines of this approach into practice. At the training courses that they were offered were hallmarked by a drastic shortage of practically-oriented content. The training team did virtually exclusively target the theoretical assumptions endorsed by this approach’s proponents along with the various properties of this approach and how it differs from traditional approaches.

-

Application of CBLT faces yet a third inhibitory variable: the classroom where teachers function are not equipped with computers and internet services. One of the defining tenets of this approach is that it encourages usage of internet services for the ultimate attainment of teaching objectives. For the staunch advocates of this approach, teachers and learners, who aspire to accomplish better and more reassuring outcomes, ought to move with the times and break free from reliance on traditional black-board-and-chalk-based lesson delivery odes: for them, there is more to teaching and to capturing and maintaining learners’ attention than such devices. Learners come into the classroom with individual variability and such variability cannot be properly attended to if the teacher slavishly sticks to the board as the only tool to use. It would be, therefore, prudent to put forward that the teachers need to receive ample training not only about the practical traits of this approach, but also how to take full advantage of the countless virtues of internet and computer technology.

-

Confronting the teachers in their attempts to act in conformity with the application maxims of this approach is the syllabus unit that they are required to cover throughout the school year. This imposition does not allow for the competencies set for each unit or set of lessons within units. Since the teaching each of the units comprising the syllabus (usually four or five ones) is strictly speaking time bound, the teacher is not allowed to devote more class time in the hope that a given competency get acquired if such a competency turns out not to lend itself to easy assimilation by the students either due to its novelty or complexity or the difficult tasks that the students are required to carry out.

List of Works Cited

Bowden, J. A. (2004). Competency-based learning. In S. Stein & S. Farmer (Eds.), Connotative Learning: The Trainer’s Guide to Learning Theories and Their Practical Application to Training Design (pp. 91-100). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing.

Grognet, A. G., & Crandall, J. (1982). Competency-based curricula in adult ESL. ERIC/CLL New Bulletin, 6, 3-4.

O’Sullivan, N. & Bruce, A. (2014). Teaching and learning in competency based education. The Fifth International Conference on e-Learning (eLearning-2014), Belgrade, Serbia.

Rambe, S. (2013). Competency based teaching: theory and guidance for classroom practice. English education, 1, 2. 42-61.

Richards, J., & Rodgers, T. (2001). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Sturgis, C., & Patrick, S. (2010). When Success is the only Option: Designing Competency-Based Pathways for Next Generation Learning. International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Retrieved 24 August 2018 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED514891.pdf.

Van Ek. (1977). The threshold level for modern language learning in schools. London: Longman.