GHLAMALLAH Nahed Rajaa

University of Oran 2

Abstract

Studies in Second Language Acquisition have frequently discussed the factors that may trigger motivation for language learning. In the main, learners’ motivation has been divided into three types: intrinsic – to learn for knowledge, extrinsic – to learn for reward and instrumental – to learn for career prospects. In Algeria, English, along with its world status, has become a requirement for job applicants. At the University, some learners of English may become anxious when they cannot identify the connection between what is taught and what is required in the labour market. Moreover, the idea of securing professional achievement and personal/social advancement is extremely attractive given the fact that English teaching serves students’ interests and meets the labour market needs. Although it is difficult to analyse all language learners’ demands and satisfy all their expectations, it is of paramount importance to address their needs, namely those related to the job market. This work approaches learners’ instrumental motivation that can serve as a driving force for the acquisition of English. In fact, it tries to consider the way those learners perceive professional challenges and the way the latter reduce their anxiety in order to influence their learning development and habits.

Keywords: Second Language Acquisition, Motivation, English, Applied Linguistics

Introduction

Investigations into the variables influencing language learning have demonstrated that several factors may trigger or hinder the acquisition process. COOK (2000) states that three major “factors” influence Second Language Acquisition (SLA) age, personality and motivation, but it is the latter that he views as the most significant.

In general, education does not target only furthering a person’s knowledge but also providing keys to professional life and career. In Algeria, English, with its world language status, has become a requirement for job applicants. However, at the University, some learners of English might become unmotivated, demotivated or even anxious when they fail to identify the connection between what is taught and what is needed in the labour market.

If we consider that (1) it is important for learners to achieve their goals and their career prospects, and (2) motivation for English learning increases when they feel autonomous and self-sufficient, we may then assume that learners can overcome their career challenges should their studies become more professionally oriented. In fact, providing academic knowledge while preparing for professional life might weaken learners’ anxiety of the unknown, increase their motivation to learn, develop their learning strategies and even make them goal-oriented. Moreover, by contributing to that, teachers might trigger positive responses from their students in order to value English learning as worthy and functional in the labour market. Correspondingly, if we acknowledge motivation as being of paramount importance in language learning, what kind of research framework should teachers adopt? And what best meets the career needs of our target demographic (our students)?

This work tries to examine the correlation between English language learning and learners’ motivation which may act as a driving force or as an instrument to face professional challenges. For that purpose, we have conducted two separate studies, the first with 34 students of English at the University of Oran and the second with a chief consultant of a recruitment agency. This work aims at trying (a) to understand students’ needs, (b) to identify if, indeed, instrumental motivation is a triggering factor for learning, (c) to analyse students’ level of motivation/anxiety facing English learning and professional challenges and (d) to consider the connection between the subjects taught at Oran University and the labour market needs.

Motivation and Professional Challenges

Research on learners’ motivation in psychology and SLA has been thriving for several decades. To understand such a topic, it may be useful to identify what motivation comprehends and how it affects students and their teachers likewise. Considered as a complex phenomenon, motivation is often defined as consisting of several factors: L2 learners’ effort, need, desire, goal and attitude during language learning. According to GARDNER (1985), motivation is the effort, goal and attitude L2 learners put into learning as the result of a need or desire to do so; it denotes “the combination of effort plus desire to achieve the goal of learning the language plus favourable attitudes toward learning the language.” (GARDNER. R, 1985: 10). Other researchers who investigated motivation have also referred to some of those factors. ELLIS (1994), for instance, defines motivation as “the effort that learners put into their learning an L2 as a result of their need or desire to learn it” (715). On the other hand, LIGHTBOWN & SPADA limit it to only two factors by stating that motivation is “learners communicative needs and their attitudes towards the second language community” (2001: 33).

DÖRNYEI (2005) believes that language learners who imagine themselves successful may become more motivated and, consequently, more engaged in the learning process. Whether motivation affects success or success affects motivation, it is clear that motivation is an important aspect of language learning. Indeed, as reported by COOK (2000), learners who are motivated perform better than others since their second/foreign language learning is much more superior. Learners’ motivation can be a stimulant to achieve a particular objective (JOHNSTONE. R, 1999: 146) as it is a complex dynamic with so many variables and orientations that may elicit achievements.

In addition, it is crucial for this article to point out that motivation reflects a cause in order to achieve second/foreign language learning as it represents “the extent to which the individual works or strives to learn the language because of a desire to do so and the satisfaction experienced in this activity.” (GARDNER. R, 1985:10). In other words, motivation needs a reason or a goal to be targeted, anticipated and even longed for and expected. Child and adult learning are not the same. While children might acquire a language unconsciously and unintentionally, adults acquire it consciously and deliberately and develop, therefore, different learning strategies and objectives. The latter can be depicted in the various types of motivation that have already been discussed among scholars. Individuals may learn a second/foreign language because of one of the following types of motivation:

-

Integrative motivation: to learn a language to be part of its people and to integrate and identify with its culture (GARDNER & LAMBERT, 1972)

-

Instrumental motivation: to learn a language as an instrument for a functional goal as obtaining jobs and other useful motives such as passing examination (GARDNER & LAMBERT, 1972)

-

Intrinsic/‘task’ motivation: to learn a language for itself or because it is attractive. This type of motivation might help learner integrate knowledge and face problems during language acquisition because learners enjoy performing learning tasks (RYAN & DECI, 2000)

-

Extrinsic motivation: to learn a language for reward or punishment such as obtaining good grades, teachers’ admiration and so on. (RYAN & DECI, 2000)

-

Machiavellian motivation: “to learn the L2 in order to manipulate and overcome the people of the target language.” (ELLIS. R, 1997: 75)

-

Resultative motivation: learners’ motivation is not only the cause of achievement in L2 but also the result of successful learning. (ELLIS. R, 1997: 75)

Motivation, along with its types, is important in language learning (BREWER & BURGESS, 2005). However, it is “integrative” and essentially “instrumental” motivations that are more of relevance to this work. Both motivations are considered as extremely substantial in language learning. According to COOK (2000), learners, who do not have either type, face difficulties during language acquisition process. LIGHTBOWN & SPADA (2001) claim that success and failure in second language learning largely depend on those two categories. Clearly, instrumental motivation can be very effective in the English learning process, and it might, therefore, enhance or weaken language learning. In fact, it may heighten a positive attitude for learners in order to make more effort, attain particular goals and meet some of their expected needs.

A complete lack of motivation may cause a negative attitude toward language learning and may weaken or hinder the process altogether. Across ‘the continuum of motivation’ from motivated to unmotivated, to demotivated or anxious, teachers need to take a step ahead to help learners sidestep the other end of the spectrum. By triggering learners’ instrumental motivation, teachers can avoid to some extent the anxiety students may feel about their professional careers. According to LARSEN-FREEMAN & LONG (2014), a little anxiety makes learners learn better; nevertheless, too much anxiety will act as an obstacle factor preventing language acquisition.

The types and degrees of motivation vary from a learner to another. Similarly, the process of English language acquisition is not the same for all learners. Teachers need to adapt their teaching to meet the requirements and needs of learners in order to capture, form and increase their learners’ motivation. However, most types of motivation are difficult for a teacher to influence since they principally depend on the learners, themselves. Instead, a professionally oriented English teaching may strengthen students’ instrumental motivation and may incite them to study harder and better.

Many students study to improve their social and economic status. They wish for a better life for themselves and their families. And without being guided or trained into how they could make their dreams come true, they might find themselves unable to face the difficulties and challenges in their learning and professional career. Some might procrastinate, neglect or even abandon their studies, others would just wait for something to happen, or they would even dream of leaving their country. Yet, whether they emigrate or not, they still have to face professional challenges. The latter cover abundant aspects of various levels within numerous stages of professional life. In fact, some examples of professional challenges may include the following, job application, job interview, career opportunities, adaptation, transition, promotion, training, leadership, teamwork, productivity, interaction, tolerance, problem-solving, anticipation, routine, unfamiliar environment, bullying, organisation, authority, etc.

The First Study

Subjects

The subjects in the present study are 34 students of English at the University of Oran who were between 18 and 22 years old and who had formal instruction in English for about 8 to 12 years at the time of the data collection. All lived and studied in Oran during their primary, middle, secondary and tertiary education. In other words, all had already studied English for seven years at the middle and secondary school. Once at University, they learn a broad range of subjects in English developing competence in form and content such as Grammar, Oral Expression, Written Expression, Linguistics, Phonetics, Literature, Civilisation, Methodology, IT Skills, Translation, English for Specific Purposes, Didactics and so on.

Procedure

The study was conducted at the end of the academic year, and only first-year and third-year students were selected. The purpose behind such a selection was to compare attitudes between those who started and those who finished their Licence Degree in English. The questionnaire distributed to the informants was designed as an attempt to answer the following questions: does the University provide enough tools to face professional challenges or does it just deliver degrees along with an exhaustive summary of theories without the ability to apply them concretely?

The questionnaire comprehends several questions correlating the informants’ opinion on the relationship between their studies and their professional future. The subjects were asked whether:

-

studying English would help them obtain a job

-

their education prepares them for a professional career

-

they might want additional subjects that are more professionally oriented

-

they feel more motivated when studying more professionally oriented subjects

-

they have career objectives met but the actual studies

Results

Although this part reports the results of a research project on the correlation between English language learning, motivation and professional challenges, the allotted space is insufficient for disclosing our study findings. Therefore, a brief synthesis of the analysis will be displayed in the form of charts and figures.

Generally speaking, most participants (82.35%) believe that a degree in English will help them secure a job and financial stability. However, among those who think so, there is a clear distinction between males and females. In fact, 83% who said yes are females as males seem to hold a different opinion. 70% of those who assume that English secures employment claim that they have more opportunities than other students because English is a world language and it is used everywhere.

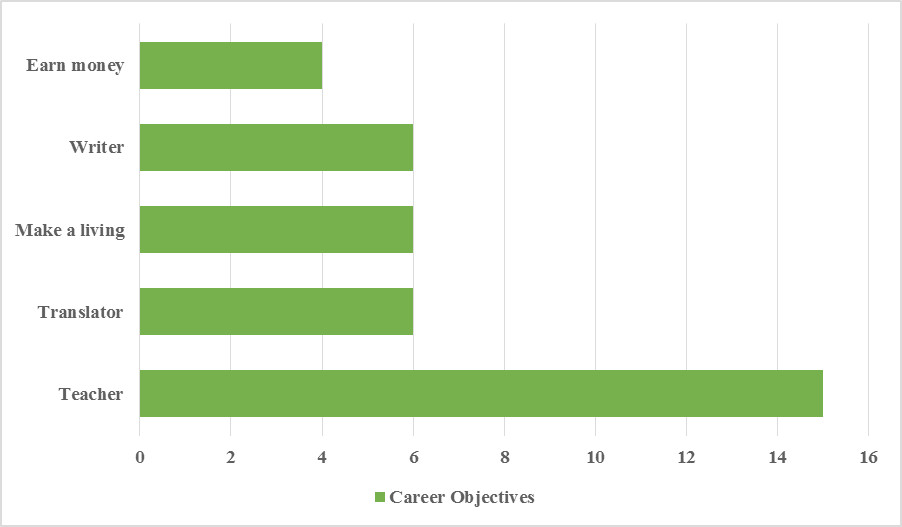

Regarding their professional aspiration, the participants express the wish to primarily become teachers as it is revealed in the following table. Although the idea of earning money is a large part of career objectives, it nonetheless comes only fifth in terms of priority expectations.

Figure 1.1 Career Objectives

Figure 1.1 Career Objectives

Nevertheless, it is significant to mention the following findings. Almost 15% of the informants believe that there are no employment opportunities in Algeria and that they have to leave the country to be successful. Unexpectedly, we have found that among the participants who think so, 80% are females and not males. The low rate of males (20%) seems unexpected because the media usually depicts male emigrants facing the dangers of the ocean. Furthermore, among the 15% who hold that view, 60% are third-year (L3)1 students in comparison to the 40% left and who belong to first-year (L1) classes. In fact, all those informants strive for a better future and wish to exit the country so that their dreams come true. 15% is a considerable percentage because it represents more than 1 person out of 6 of our students sample who reflect as such. Moreover, the main concern, therefore, is we need to look at this phenomenon from a different perspective and ask the question what the consequences of Algerian males or females are leaving family and friends? And above all what does it entail to the country?

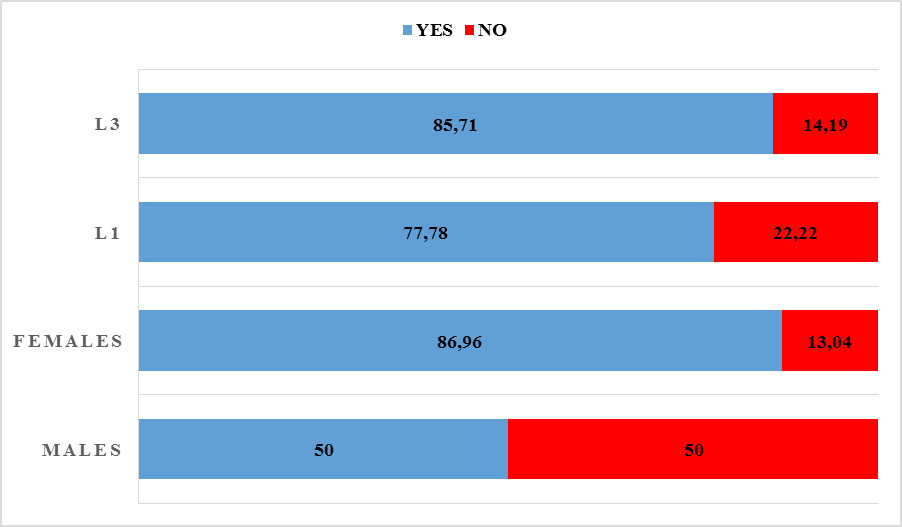

Alternatively, 79% of the 34 subjects believe that their actual studies at the university prepare them for their professional career. The following results depict the comparison in percentage between L1 and L3 and between males and females

Figure 1.2: Studies prepare for professional careers

Figure 1.2: Studies prepare for professional careers

Another significant question of the questionnaire was to enquire whether learners would feel more motivated if their lessons/subjects were more professionally oriented. Three-fourths of the 34 (76.47%) participants have answered yes; however, only half of them truthfully want additional subjects because as they have commonly conveyed “we already have enough to deal with, we do not need more subjects to learn”. As to those who wish for additional subjects at the university expressed a desire to have:

-

Conversational strategies to improve their oral skills

-

A ‘Reinforcement’ in English Pronunciation

-

Communication lessons to deal with potential employers/customers/students

-

Professional training at successful companies/institutions

-

Lessons in ethics/morals for their professional life

The Second Study

Beside the questionnaire mentioned above, we have interviewed the chief consultant of a private recruitment agency LAPEM which helps foreign companies in Algeria recruit new employees for different sectors (such as engineering, human resources, logistics, construction, mechanics, finances and so on). It is a renowned agency in Oran, and it has over 3400 job applicants/a year from all over Algeria. Although English degree holders are not numerous, the consultant states the following:

-

English is no longer a positive addition in a CV; it is a must

-

A person who masters English might give the impression of open-mindedness

-

English degrees holders are easily hired in administration services

-

In 2016, 229 job applicants were hired because they mastered English

-

In 2016, 177 job applicants who graduated in English were hired

We can visibly observe from the consultant’s statements that English is indeed an instrument for career opening and opportunities for nowadays Algeria. It can also be viewed as a positive trait in an individual’s personality since it may indicate open-mindedness.

Implications & suggestions:

-

English language teachers have to analyse their students’ needs.

-

Teachers or career advisers need to advise students on their studies and choice of a career taking into consideration their educational, personal, cultural, psychological, social and medical backgrounds.

-

Learners should not be ashamed of their career prospects

-

Language teachers may introduce learners to the multitude of possible career opportunities open to English degrees holders. Some students are simply ignorant of the market offers.

-

English teachers need to make learners perceive that English is not only grammatical rules but a means/instrument that can be exploited to fulfil their dreams as well.

-

It is also of equal importance to promote a high level of proficiency not only in General English but in English for Specific Purposes too.

Conclusion

To conclude, several studies in SLA demonstrate that motivation plays a crucial role in language learning. Besides, making our learners more motivated in their studies is a substantial and complex issue. Sometimes, teachers find themselves disabled in front of unmotivated and demotivated students who clearly aspire for more, yet they do not act accordingly because they chose not to study. Although there are different types of motivation, most of them could not be influenced by teachers. The latter might trigger a little reaction from their students, but they will not generate constant motivation during all the learning process. However, students might find their studies more rewarding if the lessons are professionally oriented, pragmatic and useful for a positive outcome. Finally, if teachers cannot make their learners motivated for education, they can at least make them avoid being anxious for their future by helping them face some professional challenges.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Farid Laidouni the chief consultant of LAPEM for providing evidence for data collection.

References

BREWER, E. W. & BURGESS, D. N. (2005), Professor’s role in motivating students to attend class, In Journal of Industrial Teacher Education, 42(3), 23–47.

COOK, V. J. (2000), Linguistics and second language acquisition, Basingstoke: Macmillan.

DÖRNYEI, Z. (2005), The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition, Mahwah; NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

ELLIS, R. (1994), The study of second language acquisition, NY; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ELLIS, R. (1997), Second language acquisition, Oxford: OUP.

LARSEN-FREEMAN, D. & LONG, M. H. (2014), An introduction to second language acquisition research. London: Routledge.

GARDNER, R.C. (1985), Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation, London: E. Arnold.

GARDNER, R. C. & LAMBERT, W. E. (1972), Attitudes and motivation in second-language learning, Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

JOHNSTONE, R. (1999), Research on language learning and teaching, 1997-98, Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

LIGHTBOWN, P. M. & SPADA, N. (2001), Factors affecting second language learning, In: C. N. CANDLIN & N. MERCER (Eds.), English language teaching in its social context: a reader, London: The Open University, 28 – 43.

RYAN, R. M. & DECI, E. L. (2000), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions, In Contemporary Educational Psychology (25), 54–67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020. Retrieved from: mmrg.pbworks.com/f/Ryan, Deci 00.pdf

1 L3 refers to ‘Licence 3’ or simply third-year students, similarly L1 refers to first-year students.